A spiritual and cultural centre

Christin RuppioIn 1956, Duisburg’s oldest Catholic parish, the Liebfrauen (Church of Our Lady) parish, held a competition for the construction of its new main church, which had been destroyed in the Second World War. Chaired by the architect Wilhelm Seidensticker, the jury unanimously chose the design by Toni Hermanns (1915–2007). Only a few days later, on 19 December 1956, the Vatican and the Land of North Rhine-Westphalia reached an agreement on the establishment of the diocese of Essen, the so-called Ruhrbistum. Thus the new building of the Liebfrauenkirche also became an opportunity to fly the flag for the faithful in the Ruhr diocese.

Urban ensemble

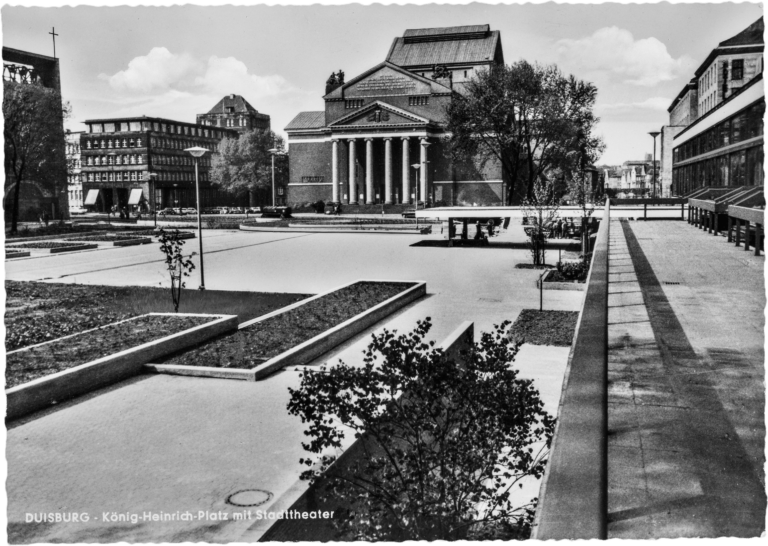

From 1896 until its destruction in 1942, a Gothic revival building on Burgplatz in the middle of Duisburg’s Old Town had been the main church of the Liebfrauen parish. Instead of rebuilding on this site, the congregation pressed for a new building at König-Heinrich-Platz in the new city centre, not far from the main railway station. As a result, the congregation also decided against restoring the tower of their church to the city skyline with the town hall and the Salvatorkirche (Church of Our Saviour). Instead, the new building at König-Heinrich-Platz had to fit into an existing urban ensemble consisting of the district court (1878/1912), the municipal theatre (1912), the public works building (1926) and the Hotel Duisburger Hof (1927). From 1962 onwards, the Mercatorhalle (#Mercatorhalle) , which no longer exists today, was directly opposite the church. It was not only the problematic situation in the ravaged Old Town, which remained in ruins for a long time, that prompted the decision to rebuild the church elsewhere. This was a programmatic move: in the immediate vicinity of cultural and administrative buildings, the longstanding parish visibly inscribed itself in the city’s new centre and present-day cultural life.

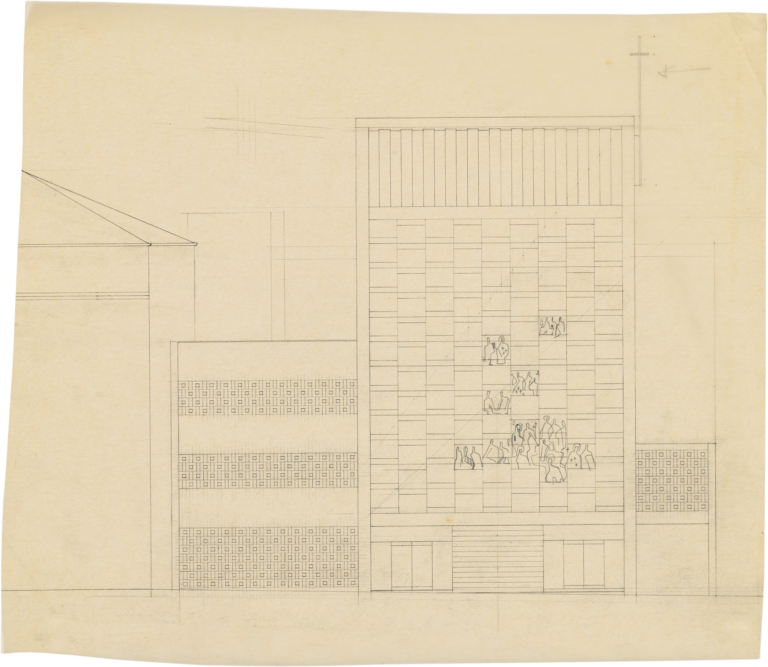

Façade and cross

A postcard photograph looking across the square from the south from the holdings of the architect Toni Hermanns in the Architecture Archives shows the exciting ensemble: the portico of the rebuilt theatre, the plain architecture of the Mercatorhalle on the right and the eastern façade of the Liebfrauenkirche on the left edge of the picture. While this artistically designed east façade marks the entrance and was prominently positioned overlooking the square, the chancel – less easily recognisable from the outside – lies to the west. Almost hidden by a tree in the photograph, the structure is nevertheless immediately identifiable as a place of worship by the cross attached to the northern side of the tower slab. An undated drawing by the architect highlights this unusual placement of the cross with an arrow. In addition, the drawing shows Hermanns’ early ideas for the artistic treatment of the façade: groups of human outlines loosely distributed over the surface.

Entrance tower

Also visible in the competition model is Hermanns’ idea of an “entrance tower” – as he himself calls this structure in the explanatory report – with a cross attached to the side from the outset. He thus avoided a tower that would loom over everything, and found a new way to make the building stand out in its surroundings. The placement of the cross at this point marks the location as sacred from the pedestrian perspective – as the postcard shows – as well as from the perspective of passing motorists. A photograph, which must date from before 1965 due to the façade being draped with a temporary design, shows the view from the corner of Landfermannstrasse and Neckarstrasse. While the cross projecting on one side is still visible from the surrounding streets today, the situation captured on the postcard with its unobstructed view across König-Heinrich-Platz has been greatly altered by the underground car park built in the meantime.

Material mix

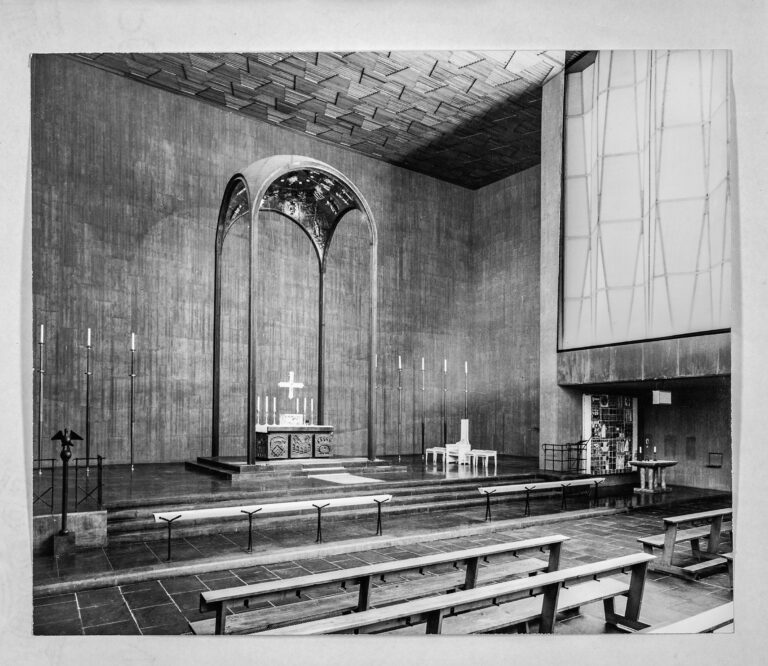

At its consecration in 1961, the Liebfrauenkirche was dubbed “Duisburg’s most audacious place of worship“. The absence of a tower visible from afar, the flat roof of the central nave with its gentle downward slope towards the west and the 1965 relief of “Moses and the Burning Bush” by the artist Karl Heinz Türk, whose flames of red natural stone cover a large part of the east façade, already give the church a thoroughly “audacious” appearance. When one enters the two-storey building and follows the steps up to the celebratory church, it is above all the two monumental windows made of Plexiglas that continue to fascinate. The drawings and model from the competition still show slotted windows that would have echoed the vertical alignment of the wooden louvres on the belfry. The first dated drawings of the Plexiglas windows are from 1959. The material mix of the white, folded plastic windows in the nave, the dark exposed concrete walls and the undulating wooden panels of the ceiling creates a remarkable impression of space and light in the celebratory church (# Lamellar Model Church). The lower-floor church of worship, on the other hand, has a low ceiling height and admits little light, creating a much more intimate atmosphere.

Venue for events

At the beginning of the millennium, the Liebfrauen parish was merged with other parishes in Duisburg, and it was decided not to use Toni Hermanns’ building as the main church. The building thus lost its function, and a discussion broke out about its possible preservation (#Church of the Holy Cross). To avert the threat of demolition, the “Stiftung Brennender Dornbusch” (“Burning Bush Foundation”) was founded in 2007, which succeeded in securing its preservation as a “church of culture”. In 2010, the upper church was secularised and has since served as a venue for events; the lower worship church is still a sacred space. Unfortunately, it was ultimately the materials the architect considered particularly forward-looking, such as Plexiglas and concrete, along with the natural stone cladding of the façades demanded by the congregation, that endangered its preservation. As is so often the case, the combination of concrete and steel on this structure led to significant damage after just a few years (#Church St Reinoldi).

New solutions

But it was above all the slate cladding of the façades that posed a particular challenge. One by one, the slates came loose from their anchors in the layer of aerated concrete inserted between the slate and the reinforced concrete for insulation during construction, until they finally had to be removed altogether. Since replacement of the slate cladding proved prohibitive because of the cost, the owner and the monument preservation department initially looked for new solutions. In this context, an energy upgrade was also considered and the Fondation Kybernetik (Cybernetics Foundation) of the Technical University of Darmstadt was consulted. After a thorough analysis, they suggested that the building stripped of its natural stone be provided with a translucent shell of multi-layered polycarbonate panels that would absorb solar energy and store it in the concrete walls.

A brutalist building that was never intended

In 2013, however, this proposal was rejected as inadequate by the monument preservation authorities. They argued that the lack of natural stone would create a brutalist building that was never intended. In addition, the structuring effect of the slates would be completely lost on an exposed concrete wall with a translucent shell, thus modifying the building’s appearance excessively. Instead, the monument preservation authorities continued to insist on a replacement of the natural stone façade, whose appearance could also be replicated with cheaper materials, such as clay and fibre cement. At the moment, the north, east and west façades of the Kulturkirche Liebfrauen are dominated by a protective layer of sprayed rendering. Above the Plexiglas window on the north façade, some of the original slates still remain, secured from falling by netting.

Furnishings

So while the exterior of the Church of Culture has certainly changed dramatically, many of the furnishings inside date back to the early days of the building. Some of them were taken from the predecessor building in the Old Town or came from the Vatican Church at the Brussels World Expo in 1958. The Duisburg city archives have a copy of the chronicle of the Liebfrauen parish, which for 1958 contains a precise list of all the transferred objects. Among the 21 items are the “canopy structure in bronze” – the canopy that still spans the chancel of the celebratory church today, – “windows on both sides” – the stained glass windows at the eastern ends of the two aisles, and “two throne armchairs” – those armchairs, one of which still adorns the chancel of the lower church of worship today. In contrast to the accounts of such acquisitions focusing solely on missing items and the scarcity of materials in the post-war period, the transfer of inventory from a World Expo also testifies to an intended opening of the Catholic Church and a confident self-presentation of the Ruhr diocese.

“Centrepiece of the overall building”

Expo 58 was the first opportunity for the West Germany after the Second World War to re-emerge as a member of the world community. For the Vatican, it was its first participation in a World Expo. The Vatican Church in Brussels featured an interior tapering towards a low-threshold altar. Toni Hermanns was also concerned with the complete focus on the altar as early as around 1958 – an idea that was to become canonical after the Second Vatican Council in 1962. In the explanatory report, Hermanns writes: “The descending ceiling, the undulation of the ceiling structure and the folded Plexiglas-glazed walls seek to achieve the greatest possible orientation of the room towards the altar”. Hermanns goes on to explain that the choice of colourless glass walls and the tranquil tidiness of the room also concentrates everything on the “centrepiece of the overall building”, allowing the congregation to reflect on itself.

Burning Bush

In the story of the Burning Bush, whose depiction dominates the church’s entrance façade, God reveals himself to humanity: a gesture of opening. And beyond that, a marking of the surrounding area as a sacred zone, in reference to the holy mountain on which the Burning Bush appears. In this image, all passers-by become witnesses to this revelation. However, the monumental tower with its low entrance zone initially looks somewhat closed. Only the belfry clad with wooden louvres and the delicate cross on the northern side soften the monumentality of this façade to some degree. Hermanns himself pointed out that the busy surroundings of the church necessitated a clear transitional area into a sphere of its own.

From the square into the interior

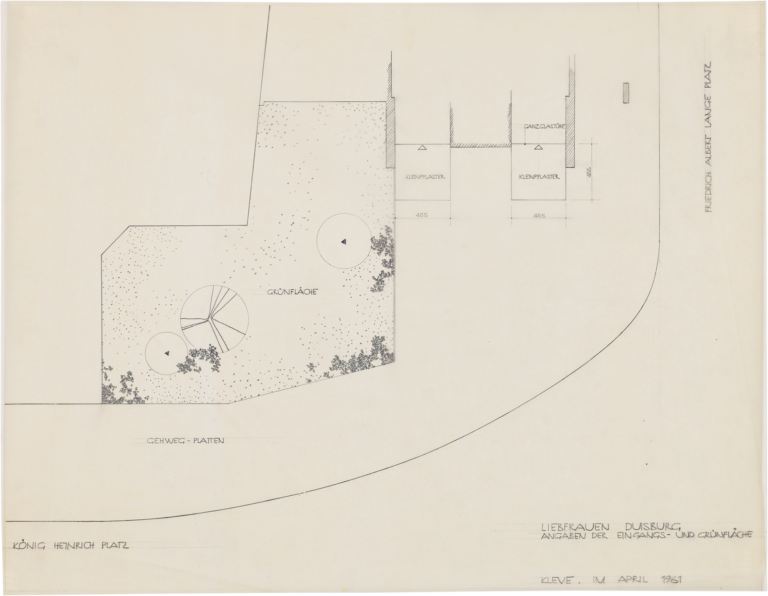

Nevertheless, there are numerous references to the outside world in the building. For example, the paving stones of the floor in the entrance area and in the church of worship bring the look of an outdoor space into the interior of the church. In a drawing from 1961, Hermanns captured this idea of the small paving stones from the square continuing into the interior. The column-mounted northern aisle of the celebration church – under which passers-by move about in their daily routines – also interlocks the building with the urban space in a special way. It is not an opening that is immediately visible, but one that represents connectedness with the surroundings.

The present text was first published in: Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, Wolfgang Sonne, Barbara Welzel (ed.): Religion@Stadt_Bauten_Ruhr, Dortmund 2021, pp. 328–343.