Gradations of sacred transparency

Ground-based firmaments and lofty monoliths

Christos StremmenosSix steep ramps and 22 steps separate the urban pavement from the atmospheric celestial images. It is not an extreme height that has to be climbed to reach this vantage point. From the man-made hill’s highest small plateau that can be reached on foot, the view of the surroundings opens up thanks to the slightly elevated, privileged position. Step by step, as one leaves the pavement of everyday life at street level, one’s perception of the surroundings is gradually conditioned with the ascent. Unaccustomed viewing angles emerge. Details come into sharper focus and are placed in new contexts. New relations can be established between things more familiar from the casualness of the everyday perspective and things that are unfamiliar, coalescing into a web of new impressions.

It is not only the surrounding landscape and the human labour embedded in it to which a strange proximity is established here from the distance of the lofty position. Even the sky, which in everyday life usually appears in sections through the petrified templates of narrow street chasms and the clearings of the squares, seems to have been brought much closer here than the summation of the physically overcome steps and ramps of the hill would suggest. The sky opening up in its planetary vastness conveys a sense of exposure. Discolourations, cloud formations and constellations appear at different times of the day and night, alternating momentously and appearing more powerful.

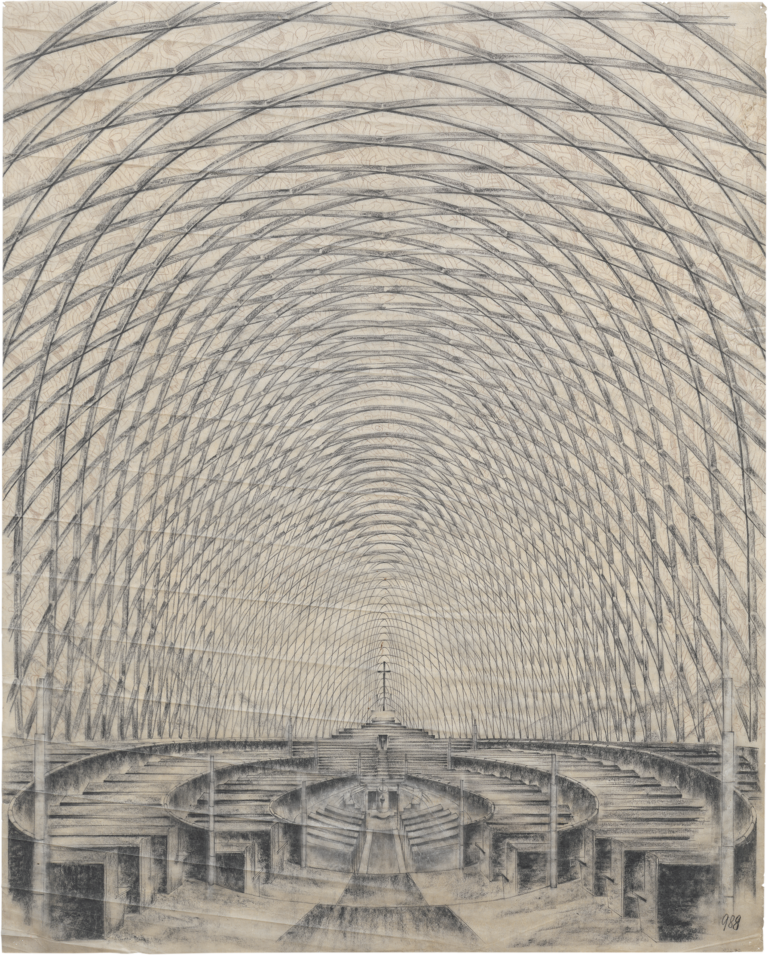

A vantage point created in this way, from which atmospheric celestial images can be captured, is in itself a small yet striking high point in the midst of the urban landscape. In this specific case, however, it serves initially as a staging post, embedded in a far more spectacular choreography. Turning away from the view from the plateau, an imposing abstract structure reminiscent of a greenhouse or an airship looms up on the other side. On entering the interior of the steel and glass shell with its net-like parabolic load-bearing structure arching over an oval footprint, one once again finds oneself confronted with an atmospheric celestial image – as before on the small viewing point, but this time captured in a compressed form by the net of the architecture.

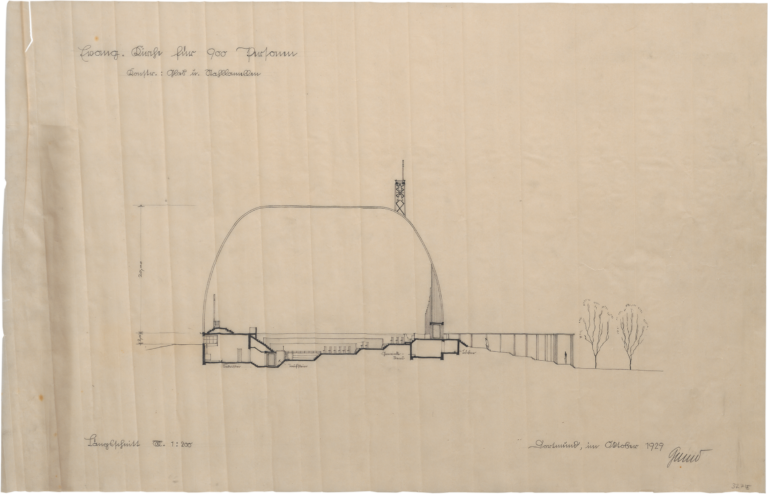

Thematising the topographical threshold to vastness, the spectacular abstract building was conceived as a church for 900 worshippers by the then Dortmund-based architect Peter Grund in a joint venture with the pastor Paul Girkon of the advisory board for ecclesiastical art, and the stained glass artist Elisabeth Coester.

Commissioned as a feasibility study, the building was to investigate the practicability of new construction methods with such materials as steel and glass for Protestant church building. The model church was designed in different sizes and presented to the general public in 1929 in the exhibition on new Protestant church building at the Museum Folkwang in Essen.

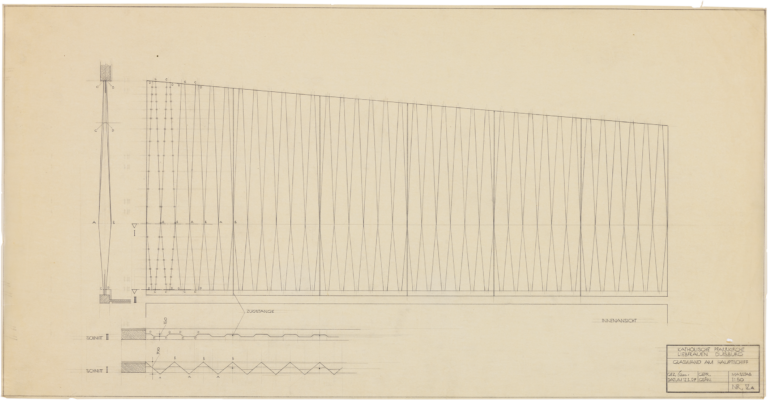

Under the heavens’ majestic vault, the ascended hill reveals itself to be a large slope-like, amphitheatrical topography. The terrace-like brick galleries with the wooden pews above them create an atmosphere of earthbound materiality. From the height of the entrance platform, a path carves axially down into the architectural mass to the lowest point of the room, which houses the font, and from there it ascends in steps to the high altar with the large cross that marks the earthly summit. The vault of heaven rising from the edges of the hill spans the “this-worldly reality” with a mesh constructed of slender struts, aspiring to a dematerialised effect. The designer calls the structurally important bars “lamellae”, which – galvanised using a system developed by Emil Hünnebeck – gave the model structure the name of “Lamellenkirche” (lamellar church).

Transparent atmospheres

The spatial load-bearing structure is reminiscent of a shell such as the US Biosphère pavilion designed by Buckminster Fuller as a transparent geodesic dome for the World Expo 67 in Montreal. Fuller sought to create a sphere of maximally transparent physical translucency. In his case, the dematerialisation of the load-bearing frame is part of a strategy of a direct visual reference to the outside world that is as barrier-free as possible. The lamellar church design, on the other hand, relies not on the transparent but on the translucent properties of the glass. The translucency, which appears in the interior perspective drawing to open directly and transparently to the sky, turns out to be far more complex on closer inspection. Flame-like textures become visible on the surfaces of the glass segments held in place by the mesh, which are part of a work conceived by the glass painter Elisabeth Coester for the vault of the model church. Through their parabolic arrangement in space, the artist’s painted glass segments seem to ignite the vault of sky like flames from the edges of the hill up to the sky. Girkon described this effect as a “vault of blazing fires of colour” evoked by the dematerialised translucent spatial envelope of painted glass.

The net structure not only takes on the role of the primary supporting structure, but also defines the envelope of the space, is the bearer of the artwork as well as a translucency that prefers not to reveal, but to allow the divine and heaven shine diaphanously in the church space.

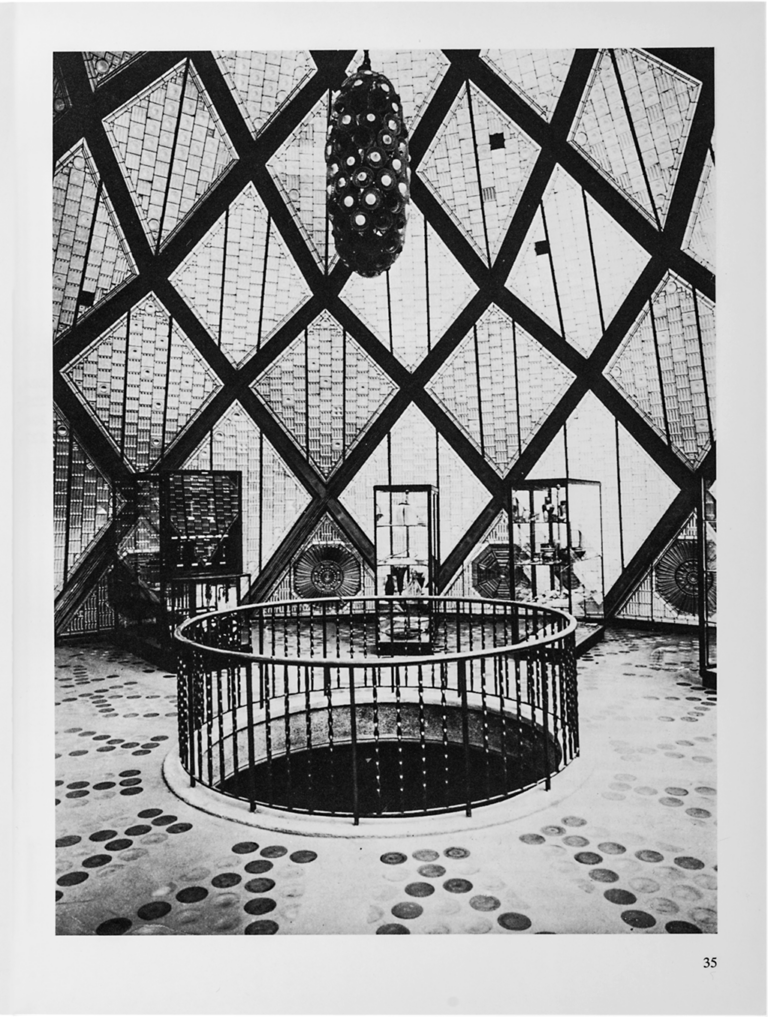

This spiritual and transcendental conception of translucency recalls the vitreous atmospheres created by Bruno Taut in his Glass Pavilion built for the Werkbund exhibition in Cologne in 1914. Designed as an exhibition pavilion for the glass industry, the building was influenced by Paul Scheerbart’s glazed architectural fantasies and served no other purpose than to show off a world of glass. With the concrete ribs of the reticulated surfaces tapering towards the top and thus defining the dome structure, Taut fills the rhomboid surfaces with double coloured glass walls. The use of Luxfer prisms and glass in different colours creates an atmosphere of reflections and coloured diaphanous effects. Here, again, the glass envelope rises above a solid, in this specific case doubly-curved and concrete, walkable plinth. Bruno Taut’s Glass Pavilion anticipates a spiritualised world dreamed of in glass, as imagined by the members of the Glass Chain in their lively correspondence and the visions committed to paper of a crystalline, light-refracting, reflective world built of clear and coloured glass. In its early days, the Bauhaus also drew on this form of crystalline translucency before turning to a primarily transparent interpretation. The Bauhaus Manifesto published in 1919 introduces Lyonel Feininger’s “Cathedral” woodcut and, with a scene of three stars suspended above the tops of church spires and shining in all directions of the space, stresses a spiritualised translucency concerned with the reflective behaviour of light in space.

From a medium of hope to a place of menace

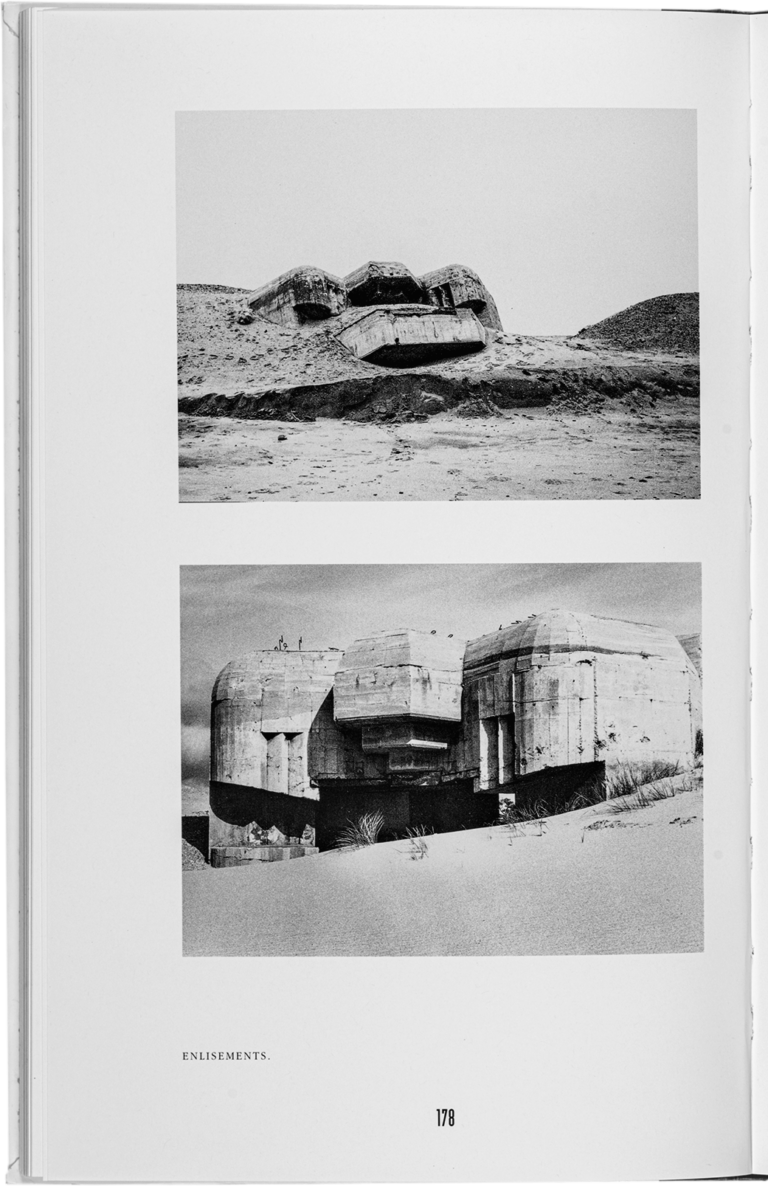

With the onset of the Nazi dictatorship, the translucent traditions of modernity were violently interrupted in Germany. Moreover, the outbreak of the Second World War, with increasing armament, turned the hope-bearing vault of the sky into a space of menace. With the deployment of new war machines that took over the sky, war claimed all dimensions of space on an unprecedented scale. Bombs dropped from fighter planes were capable of wiping out cities built over centuries in a matter of minutes. Only the solidity of the air-raid shelters and bunkers of that time seem to have offered some protection to the civilian population. The lasting effects that this all-encompassing war left in the reception of space were processed by the French philosopher Paul Virilio in several writings. He was inspired by a bunker that he happened upon during a walk on the beach in 1957.

The bunker built by the German occupation forces was part of the Atlantic Wall. In anticipation of an Allied attack, bunkers were built at certain points along the French Atlantic coast as part of Operation Todt, some of which only provided shelter for individual soldiers. This was an attempt to counter a war that was now being waged in three dimensions with the means of a ground-based and fragmented fortress. Fascinated by this archaic-looking object, positioned at the dividing line between the mainland and the sea, Virilio investigated and ultimately mapped this massive material legacy of the occupying power along the Wall in several campaigns. Virilio explains the significance of the protective space of these buildings not only through their massive shells that fend off the destructive force descending from the sky. The all-encompassing war also sets the earth in menacing motion, which is no longer “a home of security” but an “aleatoric” plane akin to the expanses of the sea. In such a fluid world without a solid underpinning, the concrete block construction offers protection not only from the bombs crashing from the sky. Without a real foundation and providing thick-walled solidity on all sides, the bunker represents a modern survival machine that provides protection even on such fluid terrain. Its aerostatic shape decouples it from the movements of the ground. With its concrete block construction ensuring the cohesion of the material, it relies on the balancing effect of its centre of gravity instead of a foundation anchored in the ground.

Protective defensiveness

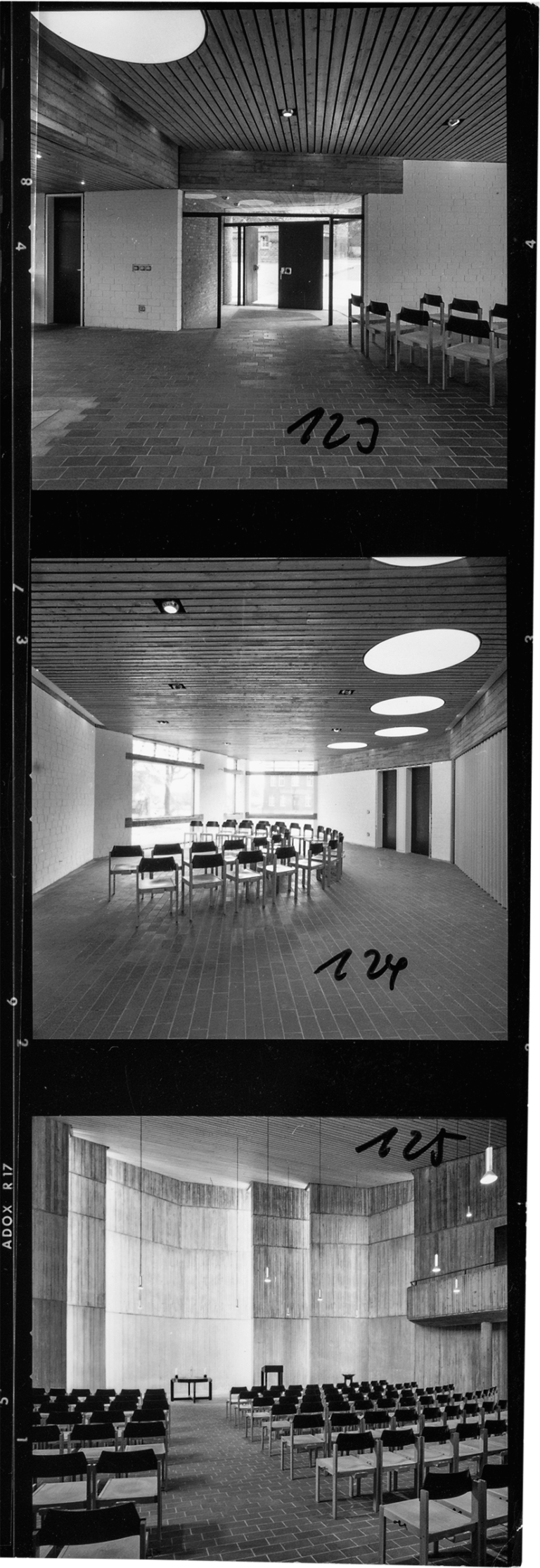

After the Second World War, sacred spaces would take up the bunker’s protective defensive qualities in many manifestations. In 1955, Le Corbusier realised his pilgrimage church Notre-Dame-du-Haut in Ronchamp, in which many contemporary commentators, including Virilio, saw a modern church space reminiscent of a bunker. An example from the Ruhr region that explores these characteristics in an aesthetically expressive way is the Protestant Friedenskirche (Church of Peace) in Herten-Disteln, built in 1969–1971 by Hanns Hoffmann. In its ground plan, the design envisages a round form joined by a polygonal section, above which reinforced concrete walls resembling a steep vertical rock face are extruded to house the nave. By breaking up the basic polygonal form in the ground plan into wall slabs and exposing them, Hoffmann makes the walls look like overlapping solid shells in the elevation. In the interior, the staggered arrangement of the walls suggests that the rock-like monolith has been broken open like a shell by the light. The invisible glass surfaces embedded between the wall segments present the solid walls in a dematerialised form by admitting the light from the side over their entire height. An unusually translucent, diaphanous atmosphere sets in, which makes the defensive monolith, as shown in the lower image on the contact print, appear sublime in its interior.

An aura of the diaphanous

Toni Hermanns’ design for the Liebfrauenkirche (Church of Our Lady) in Duisburg (#Liebfrauen Church of Culture), consecrated in 1961, also relies on a translucency similar to that in Grund’s lamellar church design, by incorporating the sky. The architect provides the concrete nave with two large openings extending almost the entire length of the side walls, into which he inserts a light folded wall constructed of glass-reinforced Plexiglas. From the outside and in daylight, the large translucent window opening looks remarkably like a component cast in concrete. At night and with the lights switched on in the nave, the church surrounds itself with a translucent aura that radiates into the urban space. The overlaying of the sky with translucent Plexiglas creates a special sublime atmosphere in the church interior. The moods of the sky are always present through the filtering folded wall, creating the impression that the nave is floating in the celestial medium.

The archive material discussed here reflects the treatment of translucency in sacred spaces since the beginning of the 20th century and the attempts to express it with the means of architecture. Unlike profane examples, the use of unambiguous transparency, as applied in a number of post-war church buildings, seems more to foster the impression of tearing open the walls of the church. In contrast, a translucency created by optical or sculptural means allows the space to enter into diaphanous relationships with the Divine Light and heaven.

The present text was first published in: Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, Wolfgang Sonne, Barbara Welzel (ed.): Religion@Stadt_Bauten_Ruhr, Dortmund 2021, pp. 246–261.