Search for new expression

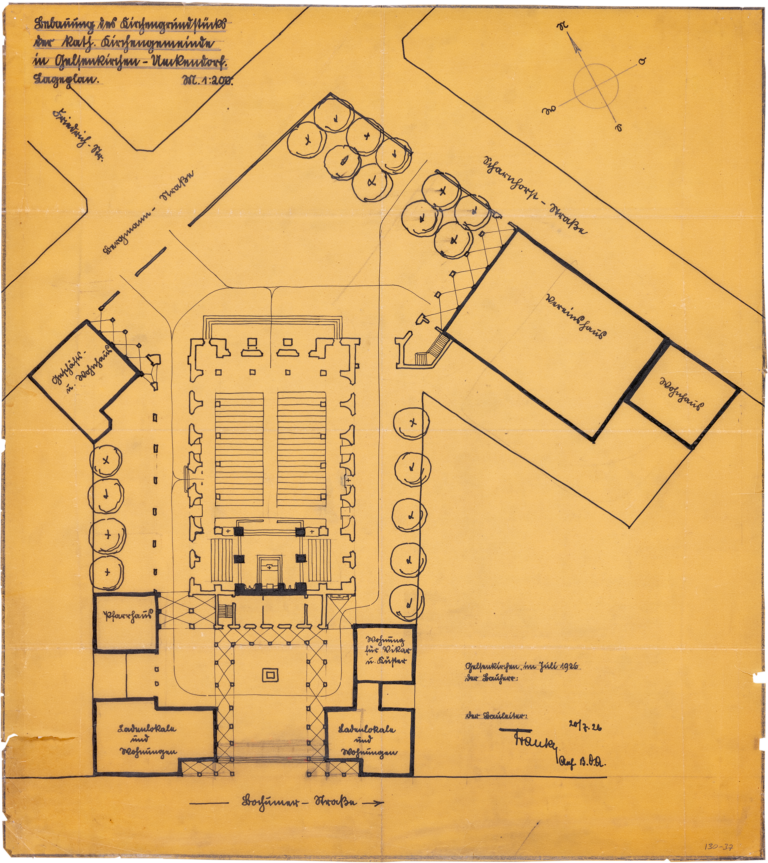

Sonja PizonkaIn 1919 and 1920, the Catholic parish of St Joseph acquired several plots of land between Bochumer Strasse, Bergmannstrasse and Scharnhorststrasse (today’s Heidelberger Strasse) that were to serve as building land for a new church in the Gelsenkirchen district of Ückendorf. The population of Ückendorf, a municipality in its own right until 1903, had grown very quickly after the sinking of the Holland, Rheinelbe and Alma collieries, and in just a few years a densely populated neighbourhood with miners’ housing estates and multi-storey residential and commercial buildings sprang up on the former farmland. Bochumer Strasse in particular, which linked the centre of Gelsenkirchen with the then still independent municipality of Wattenscheid, had developed into a lively arterial road through the district, densely built-up on both sides. It had not only a tram line, but also shops and restaurants ensuring bustling activity day and night.

A relatively narrow gap

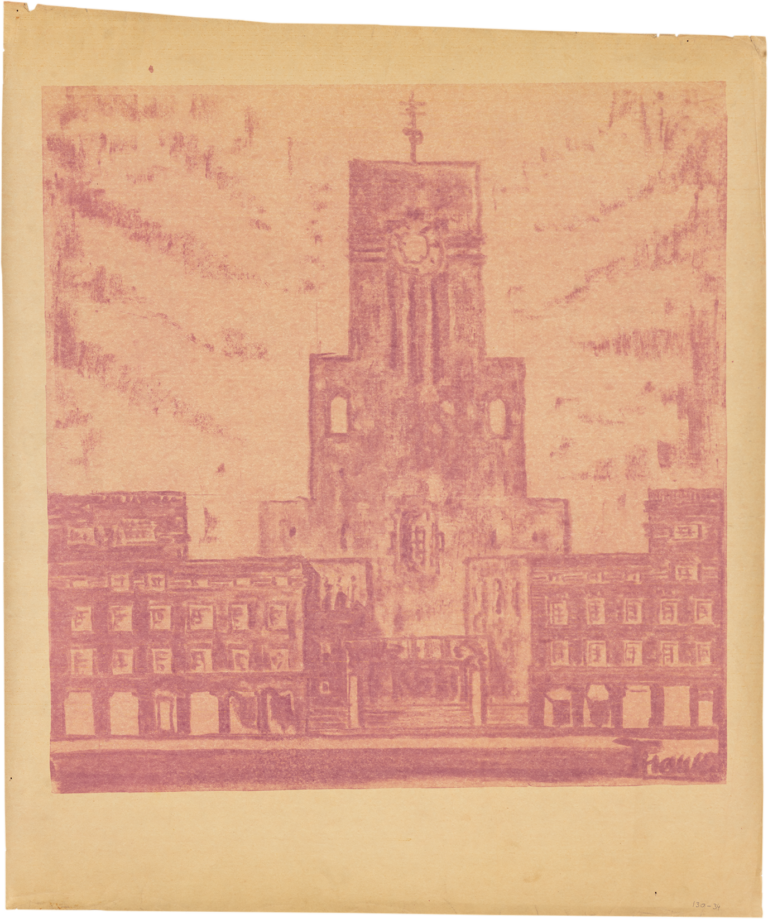

The architect Josef Franke (1876–1944), himself a resident of Ückendorf until 1908, was commissioned by the municipality to design a church building within this high-density urban setting. The Baukunstarchiv NRW holds a plan in which Franke aligned the church doorway with the corner situation between Bergmannstrasse and Scharnhorststrasse. In this design, the open area in front of the church is laid out as a tree-lined forecourt. However, the final version was to look different, and the entrance was aligned with Bochumer Strasse. At this point, however, there was only a relatively narrow gap between the existing houses. However, Franke had already worked with a similar urban situation when designing the church St Michael in Dortmund’s Nordstadt in 1912. There he had shifted the sacred building to the space behind the existing row of houses, so that this area gave rise to a church square, which was framed in turn by two uniform outbuildings inserted into the row of houses on the left and right. Franke pursued a similar design for his Heilig-Kreuz-Kirche (Church of the Holy Cross).

Impressed by this plan

Various designs show how the architect wanted to set the church façade and the outbuildings in relation to each other. None of these variants shows the characteristic cross with a triumphant Christ of brick (designed by Hans Meier), which was ultimately to grace the entrance portal. Heinz Dohmen, Essen diocese architect from 1976 to 1999, was impressed by this plan: “Franke’s building is evidence of the search for new expression in sacred architecture, leaving all traces of historicism behind him. He uses the simplest means to achieve this: an entrance set back from the continuous house façades creates distance and attracts attention – better than a towering spire that passers-by would be unable to see from their particular vantage point.” However, since the congregation had run up debts by building the church, completion of the western annexe on Bochumer Strasse was to take decades (from 1956). It was finally realised in the design language of the 1950s, so Franke’s original plan was never brought to complete fruition.

The last mass

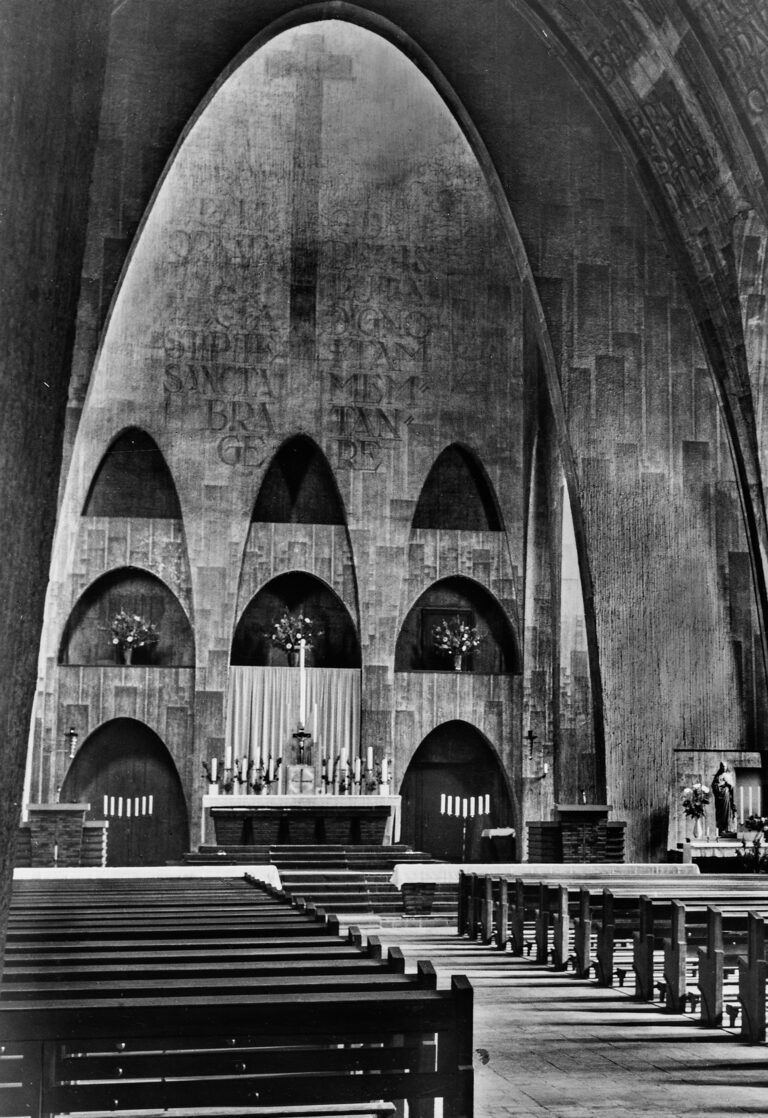

The parabolic form that defines the entrance is also an essential design element of the church interior. The original painting by Andreas Ballin, which can be seen on a historical postcard, was initially repainted in 1966 in lighter colours to designs by Gerhard Kadow, “in order to diminish the church’s somewhat gloomy character”. In addition, the chancel was redesigned in accordance with the liturgical reform after the Second Vatican Council, so that mass could be celebrated facing the congregation. In 1986, the church joined the list of monuments of the city of Gelsenkirchen, which considered not only the building but also its inventory particularly worthy of protection. Ballin’s design was finally partially uncovered, reconstructed and restored during a new renovation project (colour design: Christel Darmstadt) starting in 1993. The last mass was held around 30 years later, in 2007; due to declining numbers of parishioners, the Heilig-Kreuz-Kirche was decommissioned.

The district’s cultural centre

Although there were early ideas for repurposing and also successful temporary interim uses, conversion into a function venue was not initially considered. It was only in the context of various programmes for the regeneration of the district that the plans for repurposing took on concrete form, which ultimately led to the refurbishment and remodelling of the church building. The interplay between the church and its urban surroundings was to play an important role (#Church St Reinoldi). Regarding the Bochumer Strasse urban regeneration area, it was said: “The future face of the neighbourhood around the revitalised Bochumer Strasse will be characterised by culture, science and education. From now on, the historic Heilig-Kreuz-Kirche will be the district’s cultural centre.”

Monumental brick façade

However, this positive assessment of the sacred building and its surroundings was not always so self-evident. In 1930, a year after the church’s completion, Paul Joseph Cremers praised “this monumental brick façade, which in its austere structure, in its towering might, is worthy of the brick cathedrals of Germany’s north”. In contrast, he dismissed its surroundings, referring to the “ugly street of rented housing” and also describing them as drab, and filled with dust and poverty. In 1944, in an obituary for Franke, the verdict was similar: “The building stands in the midst of the cramped, dreary mass of buildings of the industrial city, outwardly showing many references to its neighbours, but inside in pleasantly uplifting contrast to the rectangular industrial city dwellings and blocks of flats.” In both cases, then, it was contemporary church architecture that was perceived as an example of quality building in a disparagingly described setting.

Restoring the area

Fifty years later, this positive verdict was not shared by all. In 1979, Deacon Wilhelm Zimmermann stated that Franke’s church elicited both admiration and criticism, and noted on the impression made by the building: “Anyone coming from the ‘Musiktheater’ and turning from Florastrasse into the wide Ringstrasse can see the ‘bulky’ building rising into the sky from afar, its 41-metre main tower ‘crowned’ by a majestic crucifix.” Some thirty years later, there is talk of Ückendorf and especially Bochumer Strasse as a “no-go area”. Founded in 2011, urban regeneration corporation Stadterneuerungsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG has sought to combat this image by restoring the area around the Heilig-Kreuz-Kirche with its pre-war and listed buildings with various redevelopment programmes and, in some cases, repurposing them.

Creative quarter of Ückendorf

Responsible for the activities from now on in the converted church is Emschertainment GmbH, which wishes to facilitate conferences, congresses, concerts, theatre, cabaret and neighbourhood events there (#Liebfrauen Church of Culture). The sacred building redesigned by pbs Architekten is now seen as having a bridging role between local and regional use: “The church has an impact both on the district with its neighbourhood activities and on the entire Ruhr region with its supra-regional events. The project fits seamlessly into the creative quarter of Ückendorf, which in the long term is to offer attractive cultural and recreational activities to people of the most diverse origins and age structures.”

The present text was first published in: Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, Wolfgang Sonne, Barbara Welzel (ed.): Religion@Stadt_Bauten_Ruhr, Dortmund 2021, pp. 124–137.