The most remarkable building site of Duisburg’s city centre

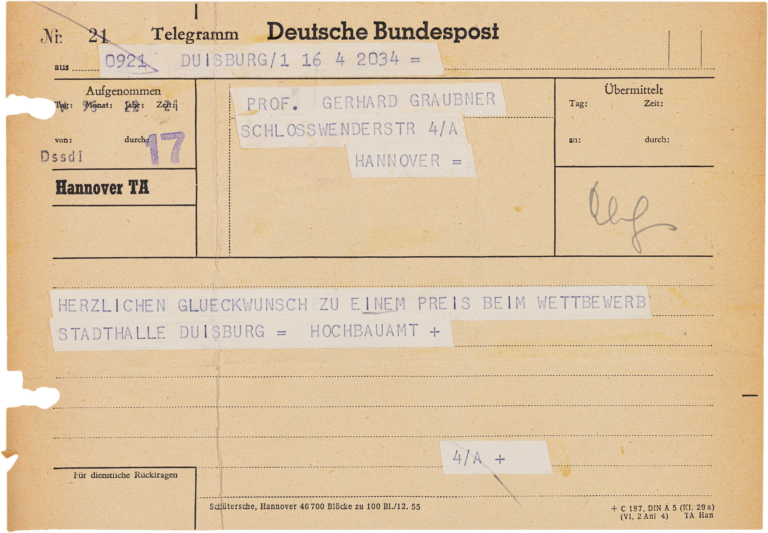

Sonja PizonkaThe design competition for the municipal hall (Stadthalle) in Duisburg took place in 1956; the plan was for a modern multi-purpose hall on the site of the concert hall that had been destroyed in the war. However, neither a first nor a second prize was awarded. Instead, individual designs were awarded “a prize”, as stated in the telegram to the architect Gerhard Graubner. A major reason for this outcome was the desire to combine the three planned (concert) halls in a single large hall if necessary.

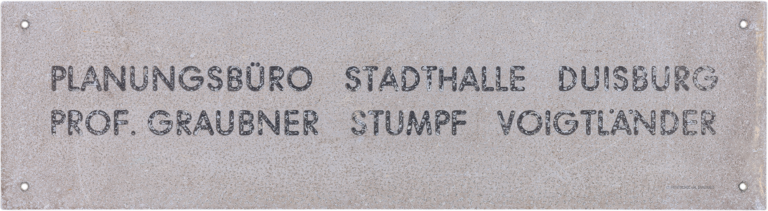

Graubner, Stumpf and Voigtländer

Egon Eiermann, competition judge, was not surprised by the difficulty of finding a satisfactory acoustic solution to this task: “Every room we build is assigned to its purpose and its intention in such a way that you can’t simply stretch it like elastic”. Although the holding of a second competition was planned, in the end it was decided to invite the prize-winners Gerhard Graubner from Hannover and the young team of architects Heido Stumpf and Peter Voigtländer from Duisburg to jointly undertake the project. Gerhard Graubner (1899–1970) had designed the Bremerhaven municipal theatre (Stadttheater) (1953) as well as the Bochum playhouse (Schauspielhaus) (1953) and produced plans for the municipal theatre in Lünen (1958). Heido Stumpf (1928–1993) and Peter Voigtländer (1927–1965) had won first prize in the competition for the design of the municipal hall in Oberhausen in 1958, so it meant they were in charge of two similar projects at the same time.

Joint design office

Voigtländer painstakingly gathered all the details of the building process, including the congratulatory telegram to Gerhard Graubner, in his files. The sign of the joint design office is also in Voigtländer’s estate. The architect was killed in a car accident in 1965, and the documents on his building projects remained largely untouched thereafter. In addition to files and plans, such items as various calendars and stamps have been preserved.

König-Heinrich-Platz

In connection with the master plan, it was said that the site of the old concert hall and the surrounding plots of land formed “the most remarkable building site in Duisburg’s city centre and require meticulous master planning to ensure a worthy design and appropriate development here at the hub of traffic from the main railway station to the city centre between cultural institutes, business premises, administrative offices and open spaces”. While the war-damaged municipal theatre by architect Martin Dülfer, that officially opened in 1912, on the north side of the square had already been used provisionally in 1946 and rebuilt piece by piece with reconstruction of the historic façade until its final completion in 1960, planning for the neighbouring site of the old concert hall progressed only at bit at a time. Reconstruction of the completely destroyed concert hall on the basis of historical plans was not envisaged; instead, the redevelopment of the surrounding area was planned, which included the planning of parking spaces, access routes and a contemporary forecourt design for the multi-purpose hall. The future construction of the municipal hall would finish off the design of König-Heinrich-Platz.

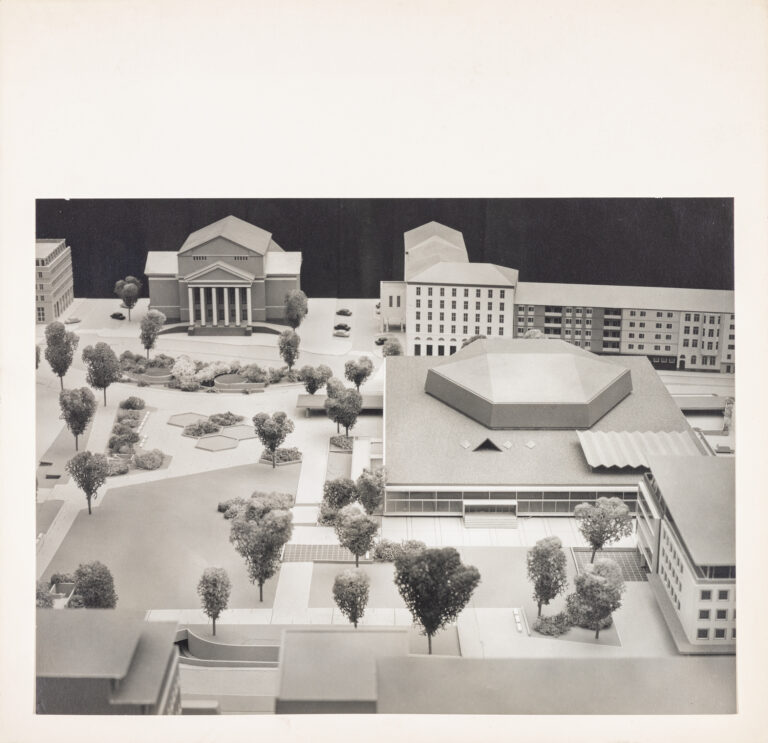

Model and construction diaries

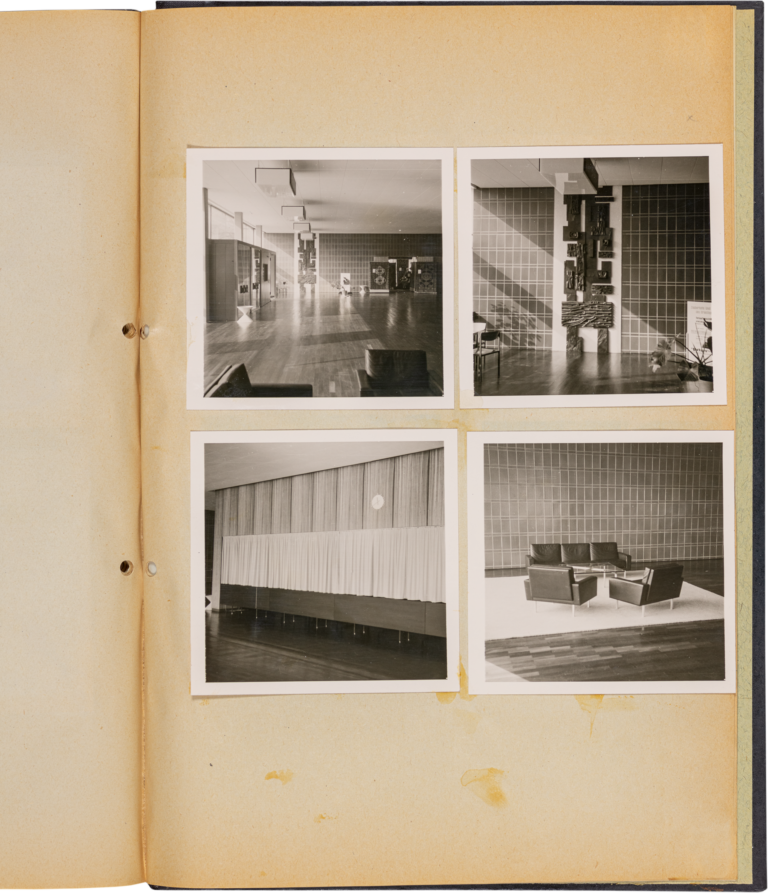

A detailed model made the planning of the new hall and the other buildings around König-Heinrich-Platz intelligible. It said: “The client’s intention and the architects’ efforts were to make this focal point attractive and to isolate it from the commotion of the city centre. Planning has been driven from the outset by three basic ideas: the grouping of urban structures, the separation of pedestrian and motor traffic, and the transparency of the structure with a glass outer skin amid masonry surroundings.” Several construction diaries also provide detailed insight into the building process. Day by day, progress and the problems of the project were documented. Numerous photographs also illustrate how things developed on site and give an impression of the first inspection of the finished structure.

Modern municipal hall

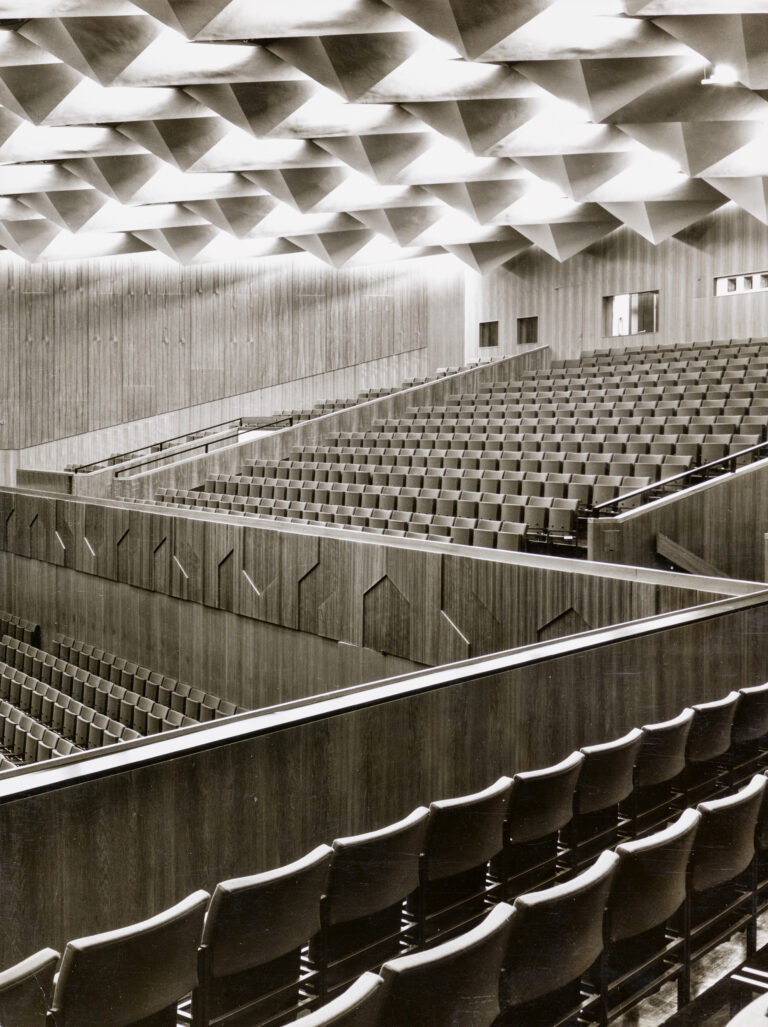

In 1961 there was a spirit of new beginnings in Duisburg, because not only the Mercatorhalle but also the adult education centre (Volkshochschule) and the Lehmbruck Museum were under construction at the time. The new municipal hall then opened the following year. The Mercatorhalle had a large and a small hall as well as a spacious foyer that could also be used for events. The team of architects had designed the large hall as a hexagon; it was praised for its acoustics, in which the structuring of the ceiling was a major factor. Concerts, exhibitions, conferences and presentations were held at the Mercatorhalle. Municipal hall director Hans-Joachim Hoerenz explained: “All these events can certainly ‘get along’. The ideas that one is not dignified enough, the other too highbrow to be staged at a single venue, do not apply to a modern municipal hall.”

Place of hospitality

This was also associated with the hope that, with the events at the hall, the city of Duisburg would become a tourist destination for out-of-town visitors. This had even been promised by the Karlsruhe architect Egon Eiermann back in 1956: “I think I can also say that you have to expect a lot of people from the wider Ruhr area – the Ruhr area is, after all, one big city – to travel over to Duisburg […].” And municipal hall director Hoerenz was persuaded that Duisburg would now no longer be perceived only as a city of industry, but also as a place of hospitality.

Monument status and demolition

25 years later, however, the municipal hall had fallen out of favour: “When the Mercator-Halle was handed over for its intended purpose, it was one of Germany’s major venues. Today it is just one of several medium-sized halls.” Although the building gained monument status in 2001, the demolition permit was granted in 2002 by ministerial decision of the supreme monument authority. It was then pulled down in 2005. In its place, the CityPalais was built, which houses an event hall (still called the Mercatorhalle), a casino, offices, and retail and hospitality space.

The present text was first published in: Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, Wolfgang Sonne, Barbara Welzel (ed.): “Und so etwas steht in Gelsenkirchen…”, Kultur@Stadt_Bauten_Ruhr, Dortmund 2020, pp. 252–265.