Architectural engineering on the Ruhr peninsula

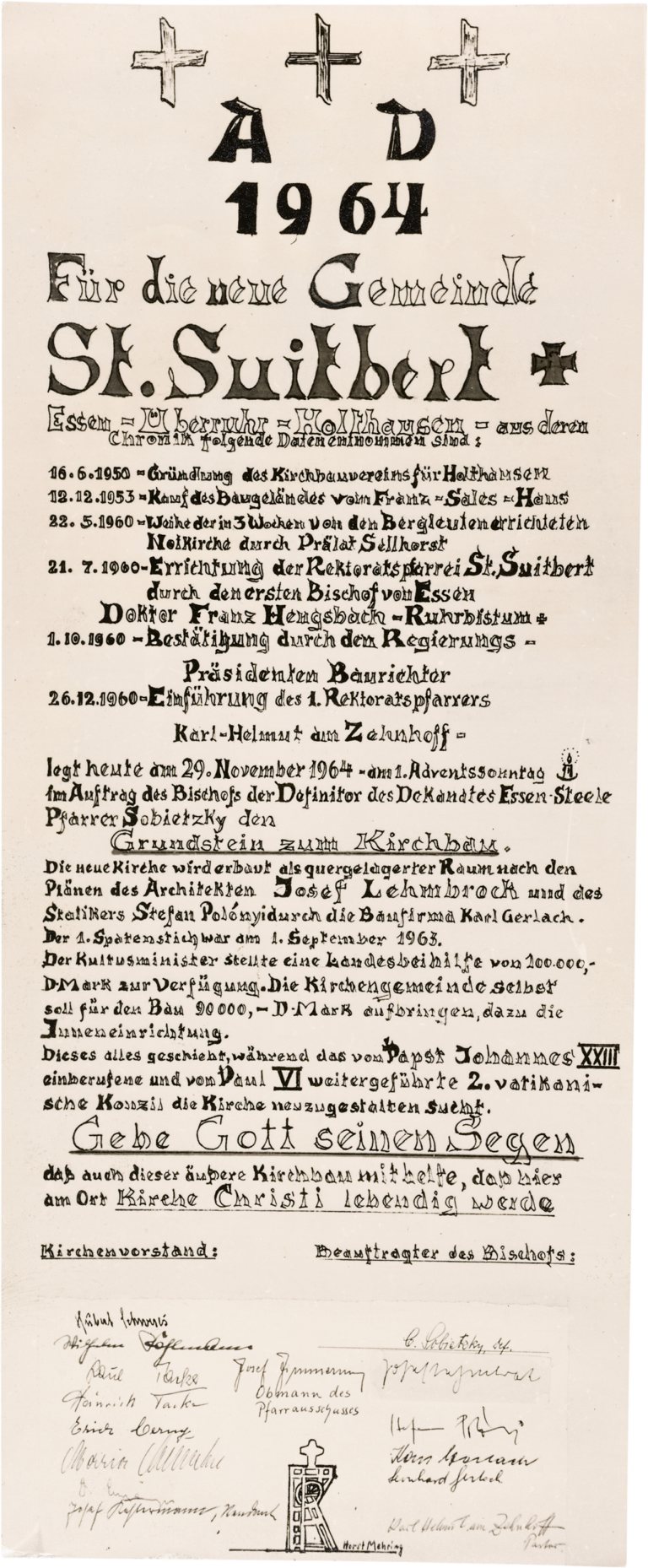

Anna KlokeOn a commemorative sheet from 1964 for the laying of the foundation stone of Kirche St Suitbert in Essen-Überruhr-Holthausen, the depiction of a cross supported by a winding tower shows the parish’s ties to the local mining industry. Thus, the chronicle of the handwritten, portrait-format sheet also explicitly points out that it was miners who, in 1960, built a makeshift church in only three weeks.

The historical background

Located on a peninsula above the river Ruhr and originally consisting of farming communities, Holthausen was not incorporated into the city of Essen until 1929. The boom in mining led to an enormous increase in population, as a result of which the rectorate parish of St Suitbert was established. This also conformed to the wishes of the first Ruhr bishop, Franz Hengsbach, who spent up to 25 per cent of his annual budget on the construction of new churches and parish buildings in order to “bring the Church to every miner’s bedside”. Financed by church tax revenues, which were still fairly high at the time, the idea behind the many new churches was to increase the number of churchgoers by being close to their homes. Buoyed by the spirit of optimism in the Church in the 1960s, the authors of the document on the laying of the foundation stone remind us that the building process was taking place “while […] the Second Vatican Council was seeking to reshape the Church”. They conclude their remarks with the intercession “that this church building will also help to bring the Church of Christ to life in this place”.

The location in the district

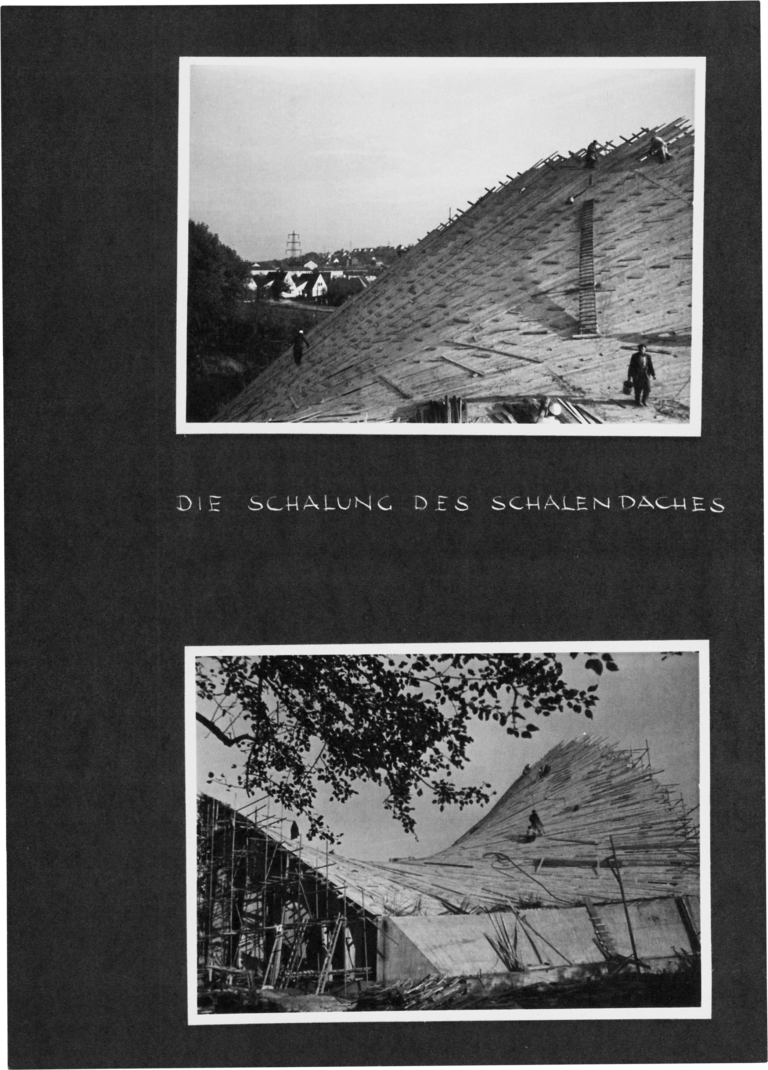

In Holthausen, which has always been a district without an identifiable centre, the establishment of a church building association in 1950 was followed three years later by the acquisition of a plot of land. As the pictures from the time of construction indicate, it is situated in the middle of sparsely built housing. Only to the north-west does the property border Klapperstrasse, a through road with a few shops. Due to its topographical location, the low height of the building of approx. 22 metres and the absence of the originally planned bell tower, the church does not stand out in the landscape. Viewed from the front, however, the organically expressive structure still arouses astonishment in its contrasting setting of middle-class suburban housing.

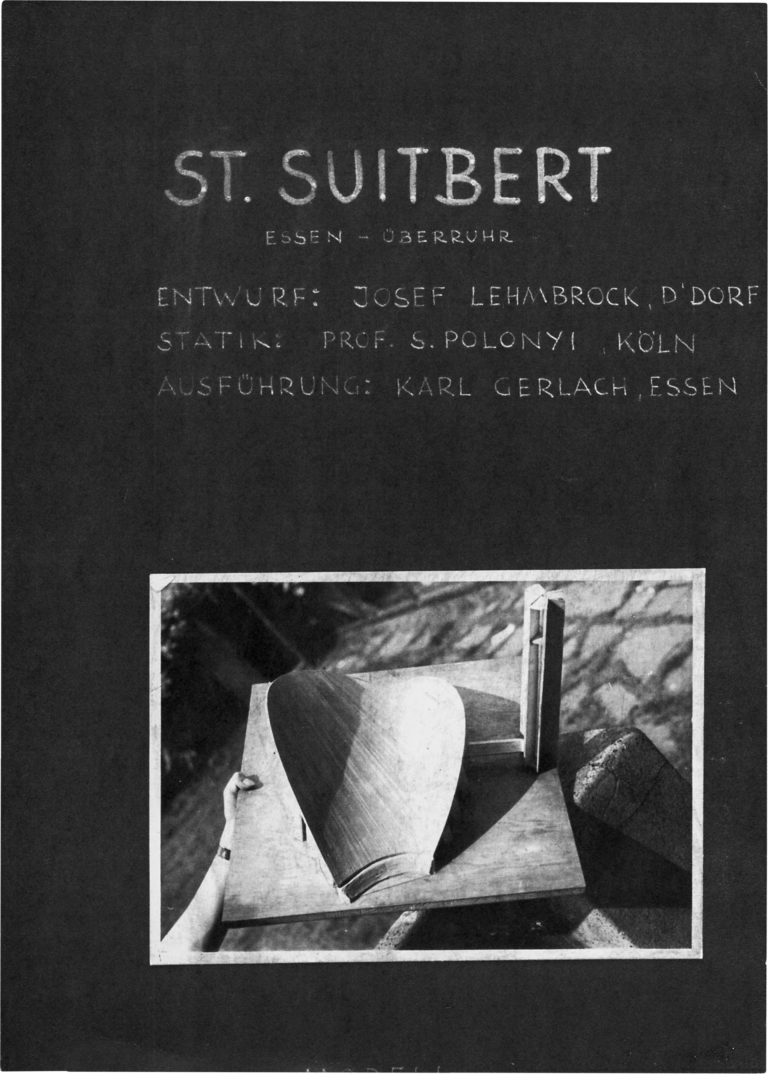

The architect

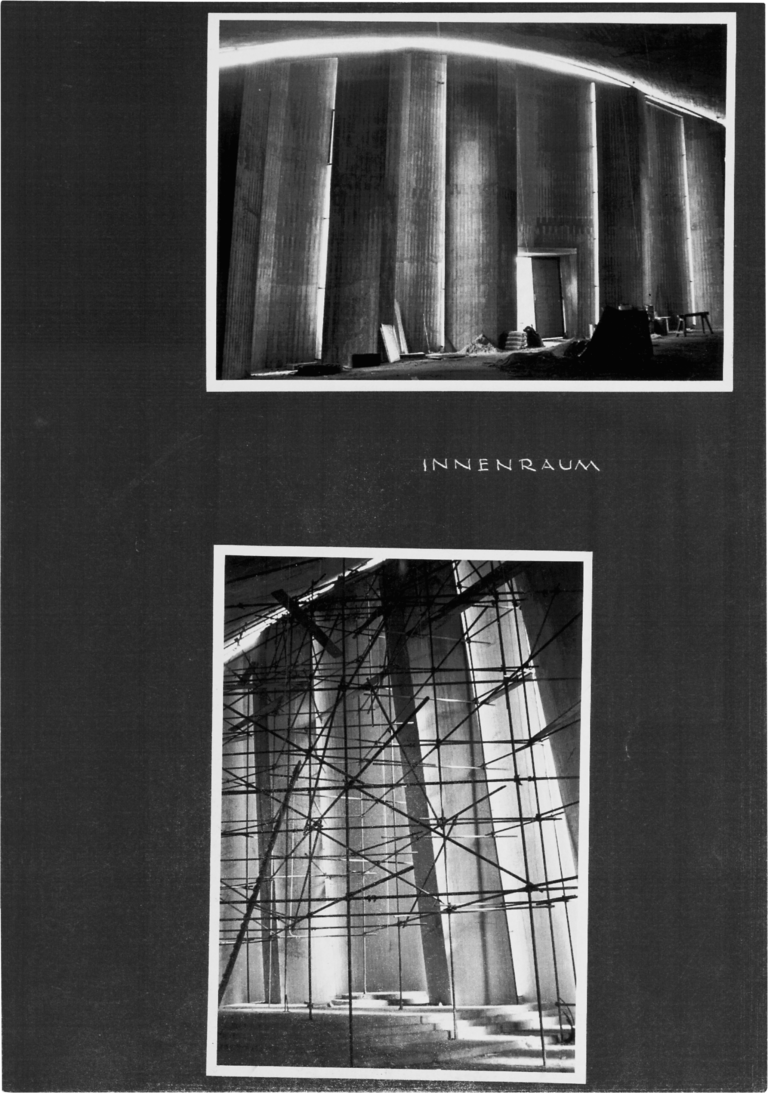

The architect Josef Lehmbrock (1918–1999) had already made a name for himself in the Rhineland with various church buildings. As the documentary photographs of the project show, St Suitbert’s roof, designed by the structural engineer Stefan Polónyi (1930–2021) as a cantilevered hyperbolic paraboloid, is impressive both outside and inside. It consists of a doubly curved concrete shell only four centimetres thick, which earned the building its nickname as the “saddleback church” and is one of Polónyi’s most important works. The Hungarian-born engineer was one of the founders of the “Dortmunder Modell Bauwesen” (Dortmund model for building construction), a (re)combining of the training of architects and civil engineers at TU Dortmund University to promote effective cooperation in construction projects – just as Polónyi and Lehmbrock exemplarily practised in Holthausen and three other churches. They made use of the then latest building techniques in order to “render palpable the old and ever new mystery of the sacred”, according to Lehmbrock in an essay from 1966 (“Gesellschaft Kirchenbau. Kirchenbau Gesellschaft”).

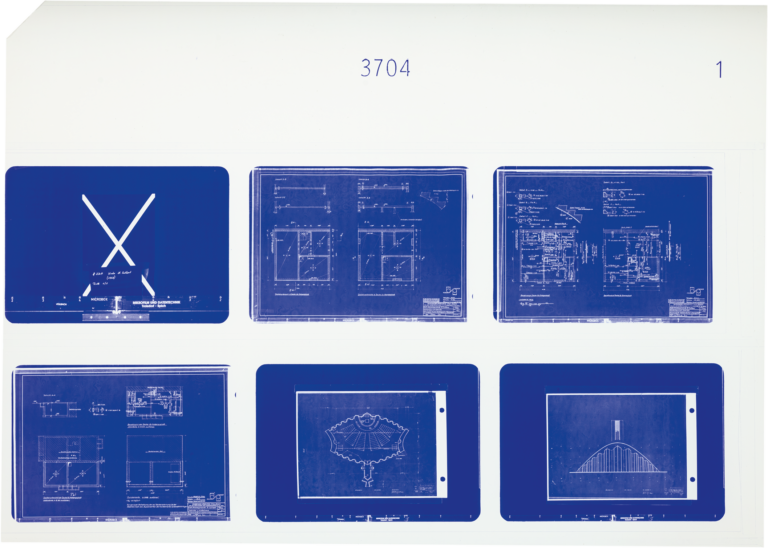

In the neighbouring district of Überruhr-Hinsel, after the demolition of the Gothic revival church of St Mariä Heimsuchung from 1874, a new cubic brick building was erected almost at the same time as St Suitbert, resembling an industrial plant in terms of shape and materials. In contrast, Lehmbrock wanted to “exploit all the scope for enhancing the church building, in order to thus distinguish it clearly from secular buildings”. In the spirit of the Second Vatican Council, he described church structure as a “rebuilding of the parish in front of and around the altar”. Very much the engineer, his colleague Polónyi archived his plan drawings in the typical manner of the time as microfiches in the practical 35mm format, which, together with the documentary photographs described above, are part of his estate at the NRW Architecture Archives.

The building description

As can be seen from microfiche no. 3704 the altar is also the anchor point of the design of St Suitbert. The solid marble altar designed by Lehmbrock himself stands raised on an altar island on the short central axis of the elliptical floor plan. The pews are aligned with it in a fan arrangement. Due to the exposed underside of the roof, the room initially has the character of a cave, reaching its highest point above the altar in its upward sweep. Taking the reverse course, the floor slopes towards the chancel. Thanks to their louvre-like arrangement, the non-load-bearing longitudinal walls allow diffuse light to enter the chancel via wall-high window slits. The walls take up the sweep of the roof’s edge, but leave space for a strip of light that makes the roof appear to float and illuminates the chancel as an arc of light. The window slits in the rear wall create a luminous curtain of concrete that additionally frames the scene (#Church St Nicolai). Due to the visibility of the stark structure and materials on the surfaces and the sparse furnishing of the church space, attention is drawn to this auratic play of light and the activities at the altar.

The remodeling of the building

At the end of the 1980s, in the course of renovation work, the building was given more pronounced “detailing” and parts of the church interior thus gained a more traditional readability. Thus, a large-scale altar cross with a Jesus figure in naturalistic depiction was erected, woodcuts of a Stations of the Cross cycle were hung up, and fixtures were added, such as a choir gallery above the entrance, a new confessional and a small Lady chapel with a noble wooden finish. The austere effect of the interior was mitigated by parquet flooring instead of the original stone floor and by a paint finish of colourful geometric shapes on the rough-textured rear altar wall. Outside, a round canopy on six columns with a conical roof has marked the entrance since this conversion phase. Neither inside nor outside, however, do the extensions and additions enter into a dialogue with the existing building.

The original design idea

The drawings on microfiche no. 3704 and the photograph of the model record a design idea that can only be imagined on the basis of the archive material: as a portal on the short central axis, Polónyi envisaged a flat longitudinal building with side entrances, which was also to link to an all-towering bell tower in the church forecourt. For reasons of cost, among others, this grand gesture was not realised and instead the steel bell frame of the makeshift church was left standing, detached from the building.

The current appearance

Between the church forecourt and the adjacent Klapperstrasse, a church car park prevents a clear connection to the urban location. A raised bed added later also marks this dividing line. The forecourt is bordered by parish buildings, some built before and some after the construction of the “saddleback church”, and whose design makes no reference to the church. To the south, the building is adjoined by meadows. Although it was the aim to integrate churches in the heart of the community, they were to “make the church precinct into an oasis in the urban environment”, according to Lehmbrock’s explanation from 1966.

The future of the building

In retrospect, the building has had little impact on development in the district. It is one of the few, albeit non-public, places in the district where people can meet and where, in addition, such an aesthetic spatial experience is possible. Thanks in part to the enthusiastic efforts of the congregation, the St Suitbert church building is to be preserved in the long term, despite the current difficult financial situation of the Essen diocese, among other things through multifunctional use in the cultural sector (#Liebfrauen Church of Culture). Despite the bitter loss for the parish, such an opening could also be an opportunity for the district, whose Heinrich colliery closed in 1968, two years after the consecration of St Suitbert. The winding tower is now part of the Route of Industrial Culture, a project of the Ruhr Regional Association. “As a contemporary document of the 1960s […] for researching and documenting the history of residential development, church and architecture“, St Suitbert, a gem of architectural engineering on the Ruhr peninsula, was added to the list of monuments of the city of Essen in 2019.

The present text was first published in: Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, Wolfgang Sonne, Barbara Welzel (ed.): Religion@Stadt_Bauten_Ruhr, Dortmund 2021, pp. 158–173.