Concrete and reconstruction

Christin Ruppio“In the thoughtful contemplation of worship, one repeatedly and with astonishment discovers the place that substance, matter, occupies in religious life. The religious act […] constantly challenges processes of a spiritual nature in man anew. But the bearer of the religious act is materiality.” Kurt Goldammer

Although the author of the book “Die Formenwelt des Religiösen” (1960), from which the introductory quotation is taken, focused on materiality, he gave not a single thought to honouring modern architecture, i.e. the visible expression of the sacred in the urban space. In fact, he regarded the efforts to pander to a “modern society” – as he called it – as a threat to the sacred. On the other hand, in the post-war period, there was also enthusiasm for the possibilities of new formal languages offered by new materials – and above all by concrete.

Reconstruction

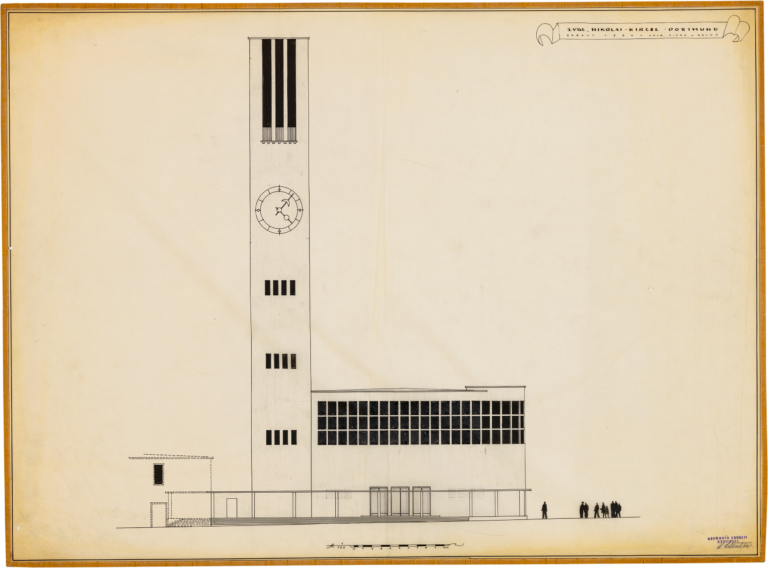

In the following, I shall focus on two Protestant churches in Dortmund that have made their mark on the urban landscape and reveal a great deal about the relationship between concrete and sacred buildings: St Nicolai and St Reinoldi. Neither dates entirely from the post-war period, but both were rebuilt in this period by the Dortmund architect Herwarth Schulte and are thus present in the holdings of the Baukunstarchiv NRW. St Nicolai was Germany’s first reinforced concrete church in 1930 and is thus a landmark for concrete in the context of religious architecture. After being damaged in the Second World War, it was first repaired in 1947 and underwent restoration until the 1960s. St Reinoldi, on the other hand, looks at first glance to be a purely historicist reconstruction and only on closer inspection reveals a remarkable use of concrete. St Reinoldi was rebuilt from 1947 to 1956 with great public interest.

In the face of some resistance

In 1928 – a year before the construction of St Nicolai began – a work entitled “Beton als Gestalter” was published that explored the new possibilities of concrete from the engineer’s and architect’s point of view. This publication emphasised the close cooperation between artists and industry – i.e. the producers of the material – as well as the scope for finding entirely new forms by using a material that can be freely shaped. However, this appeal cannot be interpreted as a sign of a general acceptance of this building material, but rather as an indication that it was in need of advocacy at the time. The implementation of St Nicolai with exposed concrete and – apparently – without borrowing from historical forms also had to be pushed through in the face of some resistance. The Dortmund architects Peter Grund and Karl Pinno won the competition announced in 1927, but the higher church authority in Münster went so far as to prepare an alternative design to thwart the project. Nevertheless, St Nicolai was consecrated in 1930 to the designs of Grund and Pinno. In the meantime, the architects had modified the competition design and replaced the gable roof with a flat roof, which made the building even more reminiscent of New Objectivity architecture.

Off-form exposed concrete

At the intersection of Lindemannstrasse and Krückenweg (now Wittekindstrasse), St Nicolai formed a hub in the district south of the city centre in around 1930. It served as a link between the city centre and the districts of Hörde and Hombruch, which were newly incorporated at the time of St Nicolai’s construction. On the other side of Hindenburgdamm (now the B1 road), the Westfalenhalle had been opened shortly before. St Nicolai thus also had to hold its own against some already existing, high-profile buildings. The off-form exposed concrete of the façades and interior commonly found on industrial buildings succeeded in attracting the desired attention without being ostentatious. Paul Girkon, head of the advisory office for ecclesiastical art and involved in the construction of St Nicolai, wrote: “The poor and meagre, this […] material has here become a principled testimony to the blessedness of spiritual poverty, a radical ascetic rejection of all outward additions, of ornament and accessory, of representation and façade”. Regarding the nature of the material, Girkon argued against critics who saw the building of churches as a waste in the late 1920s, a time dominated by poverty and unemployment.

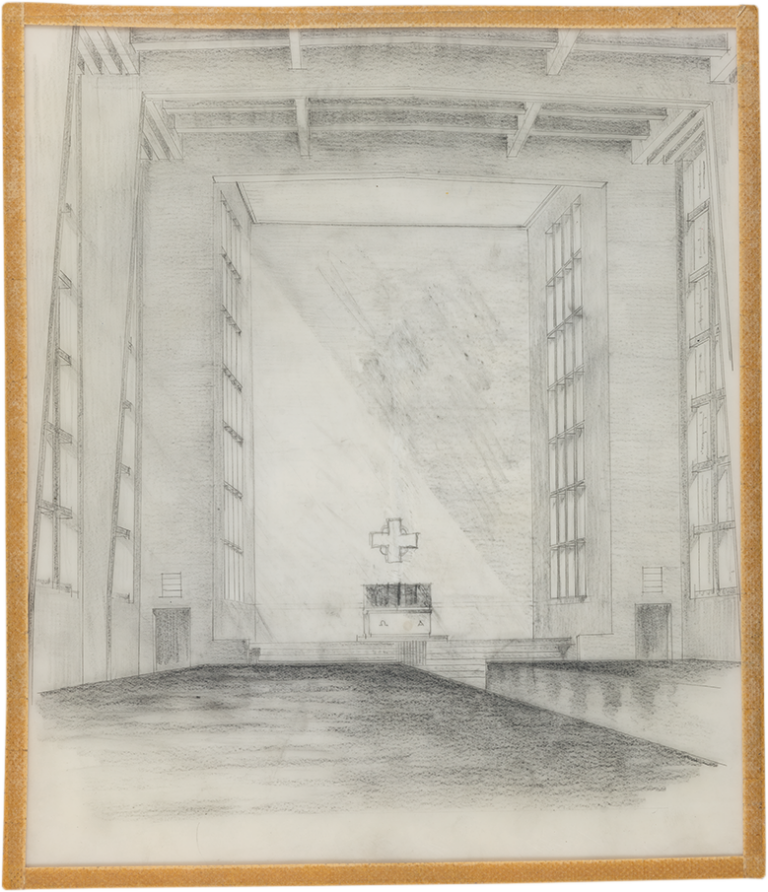

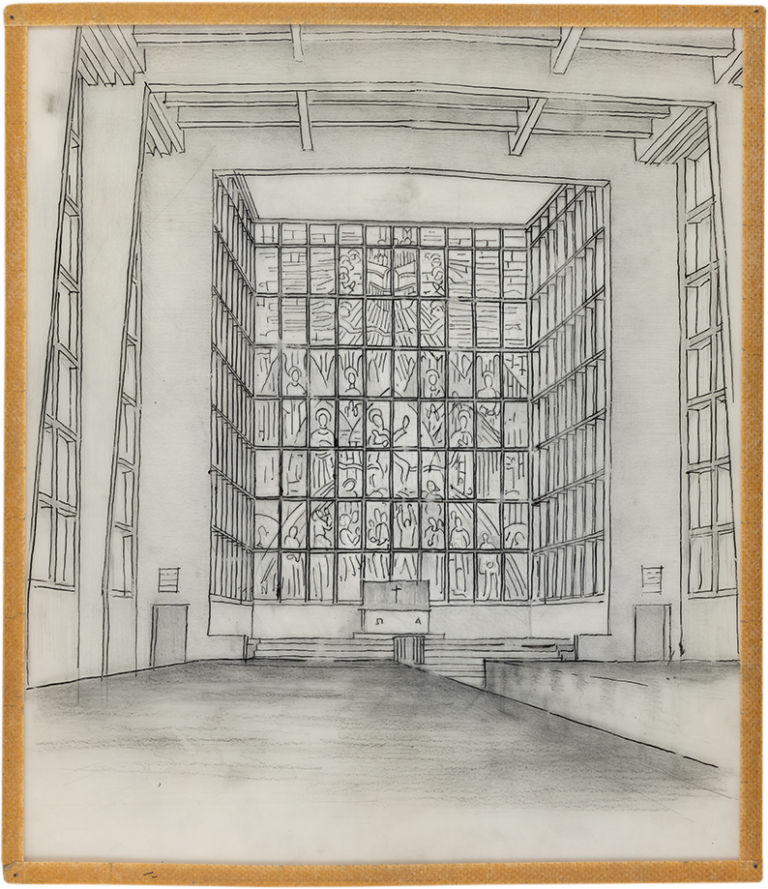

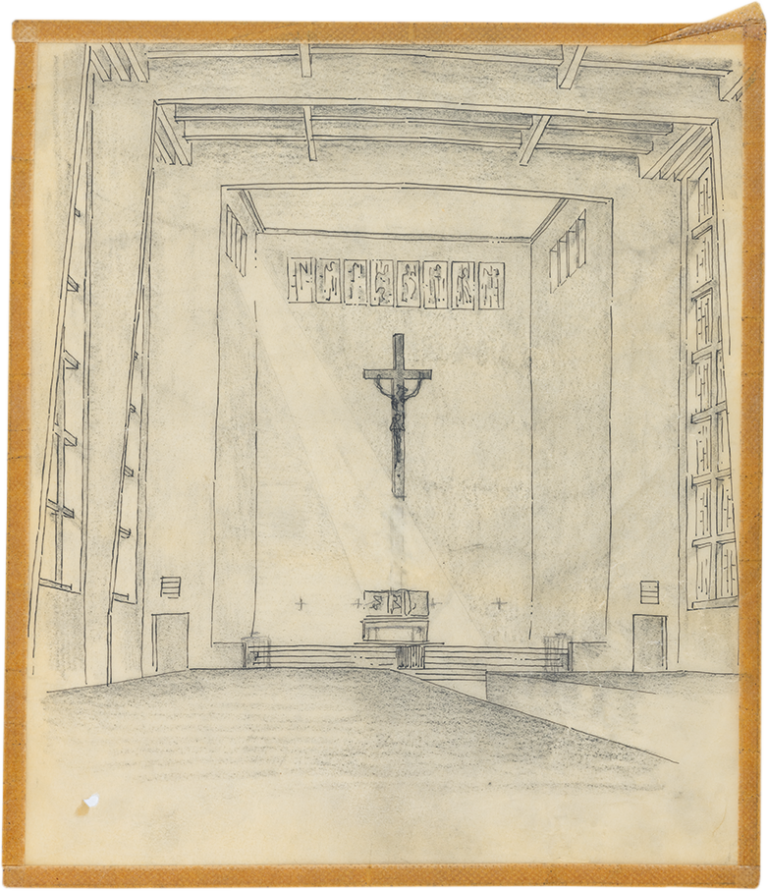

Importance of an architecture of light

To address the criticism of the incompatibility of new materials and forms with faith, Girkon claimed a direct link between reinforced concrete building and the sacred spirit of the Gothic. Reinforced concrete had already been used by Auguste Perret on Notre Dame du Raincy (1922/1923) near Paris and by Karl Moser on the Antoniuskirche (1927) in Basel. They both demonstrated how the possibility of erecting seemingly entire walls of glass that goes hand in hand with reinforced concrete is certainly reminiscent of Gothic buildings. A series of small-format perspective views in Herwarth Schulte’s estate shows that he was particularly concerned with the importance of an architecture of light for the effect of the chancel during the reconstruction of St Nicolai. In some drawings, the glazing behind the altar is detailed, while in others it seems almost transparent, and Schulte tended to sketch light incidence from the side. Schulte’s drawings clearly show the striving of the space towards the altar. The trapezoidal floor plan tapers towards the choir and thus enhances the concentration on the altar.

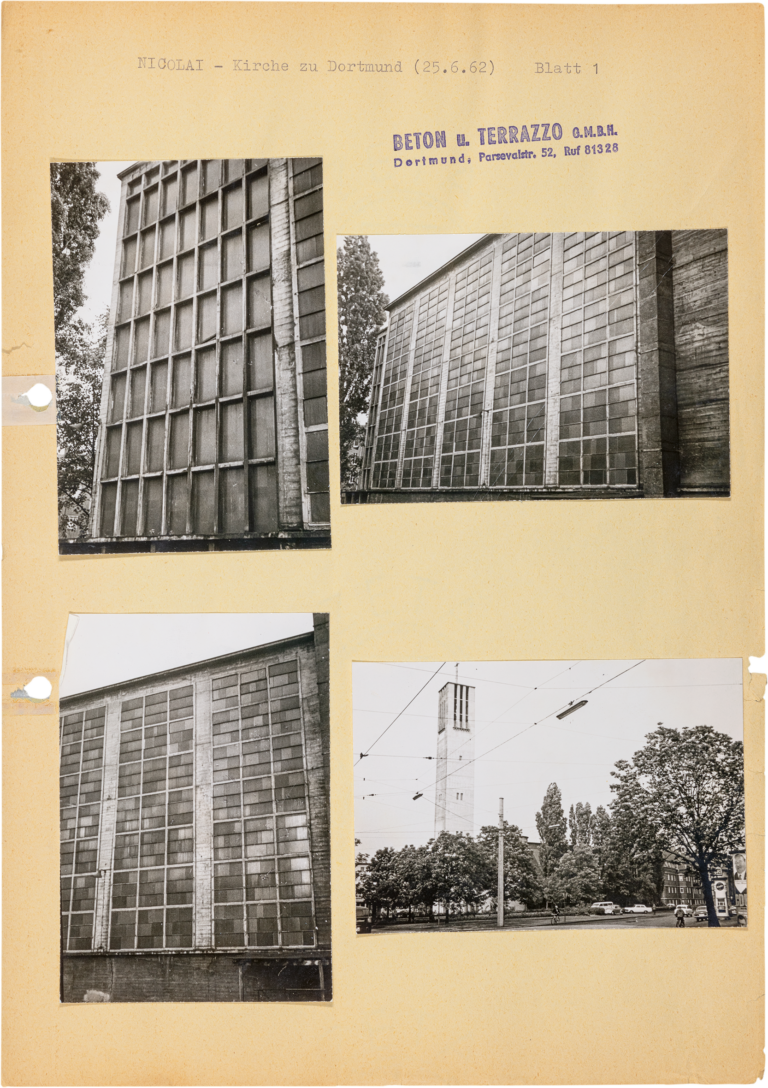

Impression of a continuous glass surface

This was accompanied in the 1920s by a discourse on the increased importance of the Eucharist and ritual acts in the Protestant church – in contrast to a predominant concentration on the word of the sermon. While the nave of the aisleless church of St Nicolai is articulated by the inwardly extending supports of the reinforced concrete construction, this approach was abandoned in the chancel in order to reinforce the impression of a continuous glass surface (#Lamellar Model Church). The concrete trusses regularly spaced in the nave were once again emphasised by Grund and Pinno by illuminating them – as well as a monumental cross in the chancel – with bands of soffit lamps. This illumination, especially in combination with the exposed concrete walls, was reminiscent of the advertising displays in the city centre. This form of lighting was not renewed during reconstruction.

A beacon in the urban space

In views of the façades, Herwarth Schulte drew in the glass fronts as black surfaces, which approximates to their actual appearance from the outside. The windows only achieve their striking effect as luminous walls when viewed from the inside. In accordance with the clients’ demands, the building was conceived from the inside out, but its positioning in the urban setting was not neglected. Girkon summarised this special challenge as follows: “As a building task, the reinforced concrete church […] shows with rare clarity the two focal points of the problem: the exterior as a dominant urban feature, as a widely visible and effective testimony to the sacred site in the living space of the city – and the interior as a ‘built’ liturgy, lending spatial form and architectural shape to ritual”. Although its façades initially seemed to be closed, St Nicolai was already a beacon in the urban space in around 1930. The shining cross on the slender, tall tower, characteristic then as now, made St Nicolai visible far beyond the boundaries of the district at the time it was built and thus a landmark for several generations.

Damage to the concrete

Grund and Pinno also added a clock with illuminated numerals and hands to all four sides of the tower. Schulte initially included the clocks in his reconstruction plans, but in some undated illustrations he broke away from the sobriety of the original and experimented with more ornate hands. Several views of the tower, dating in some cases to 1960, ultimately show it without a clock, which brings the solid exposed concrete surfaces even more to the fore – a façade that remains a challenge in terms of monument preservation to this day. Schulte’s files from around 1960 already contain extensive correspondence on damage to the concrete. In the course of this, photographs were exchanged between Schulte and the producers in which the tower can be seen immediately after its completion. Likewise, it becomes apparent how water can become a perpetual problem on concrete façades with large glass windows. In the years that followed, there is repeated correspondence on maintenance and a compilation of various solutions to the preservation of the exposed concrete façade. In the end, however, the tower had to be rendered to protect it from further damage. Since the tower of St Nicolai only has stair landings but no floors, it offers an impressive spatial experience. From the ground, one looks up the exposed concrete walls to the belfry.

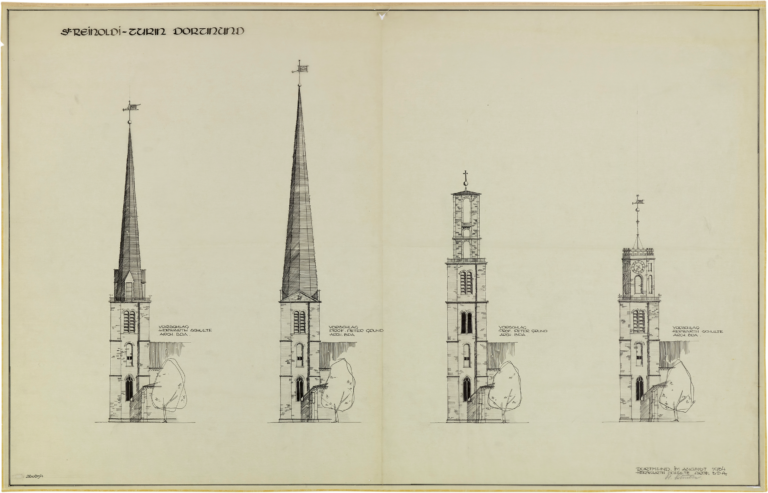

Proposals for tower variants

And in the city church of St Reinoldi, one is also surprised by exposed concrete walls inside the rebuilt tower. Hailed in the 15th century as the “Miracle of Westphalia” with a height of 112 metres, it collapsed for the first time in 1661 and was rebuilt, but then with a baroque cupola. In 1944, St Reinoldi was destroyed down to its side walls in an air raid, and about half of the tower collapsed. Dortmund’s city centre thus lost a landmark that – much longer than the tower of St Nicolai – had been an important point of orientation in the city and, above all, a source of urban identity. It is therefore hardly surprising that the population showed a keen interest in the rebuilding of the church and voted on the outward appearance of the tower in a newspaper survey in 1948. The Herwarth Schulte collection contains proposals for tower variants by various architects. Among them is a sheet of designs by Herwarth Schulte and Peter Grund side by side.

Deviation from the baroque model

The rebuilt tower resembles the previous tower in its baroque form, but was realised with an even loftier octagon and a higher dome. Inside, on the other hand, Herwarth Schulte opted for a clear deviation from the baroque model by not concealing the concrete formwork, but leaving it visible as a structural element and a clear sign of the reconstruction. Medieval building fabric and new designs in keeping with medieval structures meet in St Reinoldi at structural seams that are often only visible to the expert eye. The fair-face concrete in the tower, on the other hand, clearly testifies to its status as a rebuilt church. Before the main entrance was moved from the west portal to the south façade, the concrete-lined tower chamber was the first thing visitors saw of the church’s interior.

The present text was first published in: Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, Wolfgang Sonne, Barbara Welzel (ed.): Religion@Stadt_Bauten_Ruhr, Dortmund 2021, pp. 40–55.