From Scharnhorst to Assisi

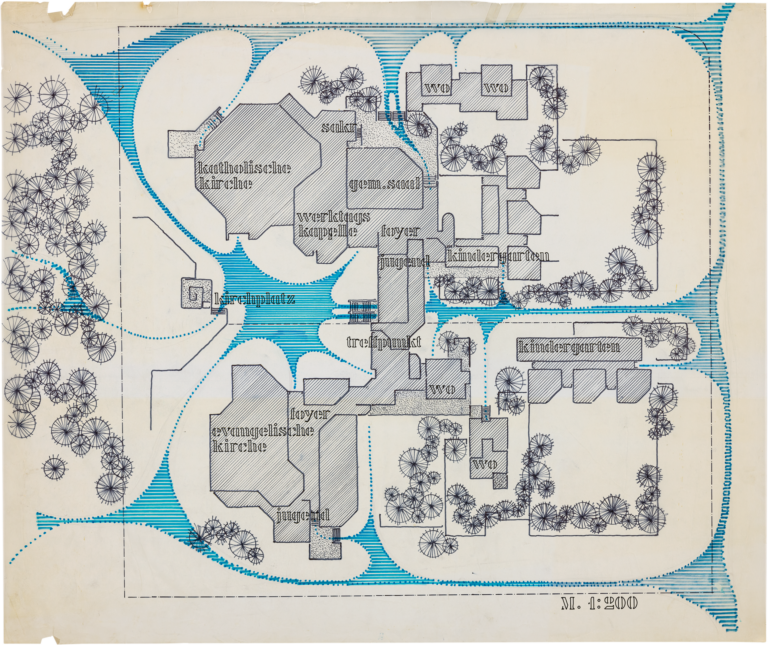

Anna KlokeThe inventory of works belonging to the estate of Mechtild Gastreich-Moritz (1924–1998) and Ulrich Gastreich (1922–1997) at the Baukunstarchiv NRW documents that the Dortmund architects had already worked successfully as a team during their studies at the Technical University of Munich (1946–1951), when they jointly won the student competition for the construction of a hall of residence for the Bonn Students’ Union (AStA Bonn) in 1951. In the course of their careers, the two of them developed an architectural language that at times evolved quite formalistically from the interplay of geometric forms and at other times was conceived in a strongly functionalist manner working from the user’s needs. For example, the floor plan of the Dortmund Naturkundemuseum (natural history museum) (designed 1955–1975, built 1978–1980, #Naturmuseum Dortmund) is derived from the crystalline structures of the minerals exhibited in the museum. In contrast to this, the ecumenical community centre in Scharnhorst (designed 1968–1971, built 1971–1974) of the Protestant Friedenskirche (Peace Church) congregation and the Catholic Franciscan congregation, which they planned together with Richard Riepe, is instead a room layout in physical form: the site plan of the centre on a scale of 1:200 shows the building as an aggregation of rooms of the most diverse, functionally designed and interlocking floor plan formats, arranged in a semicircle around a forecourt.

The church as a meeting place

In the middle of the plan is the word “Treffpunkt” (meeting place), which is ultimately the building’s guiding theme. Both denominations wanted to create a place to meet and socialise for the more than 17,000 people who had moved into the large Scharnhorst-Ost residential estate, most of which was built as social housing from 1965 onwards. They recognised the social hardships, which were also due to a lack of developed infrastructure in the neighbourhood, and together they put themselves at the service of residents. “People from all over the Federal Republic with many different worries and hopes suddenly became neighbours. […]Francis of Assisi, to whose name and mission our young suburban parish is dedicated, went to all people […]. The Franciscan congregation wishes to put his testimony to Jesus Christ into practice in new forms”, according to the declaration in the certificate for the laying of the foundation stone of the Catholic part of the community centre.

“New forms”

These “new forms”, user-oriented, deliberately eschewing grandiose gestures and a traditional church architecture vocabulary (#Church St Nicolai), are visible in the ground floor plan. The blue hatching marks the network of paths that extends as a connecting element across the site laid out like a campus with landscaped courtyards. As can be seen from the plan, this is an early design phase in which the ecumenical centre was already spatially divided by denomination, but still structurally connected. Whereas the beginning of the planning process envisaged a centre put to shared use, including the sacred spaces, cooperating but structurally separate centres were finally realised with a shared forecourt.

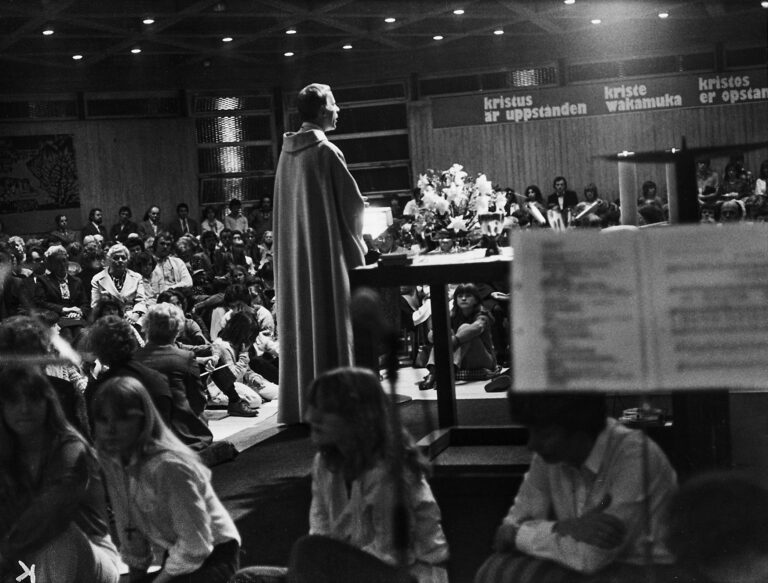

Today, an open pedestrian path runs from the forecourt past the pre-schools towards the shopping street. Despite the outward division into two parts, the 1-to-2 storey centre with mostly flat roofs and artificial slate façades was deliberately given a uniform design in keeping with the ecumenical idea. Not only the centre, but the entire large housing estate built by the “Neue Heimat” housing association as an answer to the prevalent housing shortage was to be perceived as a single design unit “because of the size and importance of the project”. An archived photo from the time of construction illustrates the visual merging of the façades of the community centre with the surrounding housing development. Only the octagonal structure above the chancel of the Catholic church stands out in the picture. This demonstration of commitment to the community and almost humble simplicity can also be found in the gathering for a service of the Franciscan congregation, documented in another photograph from the estate. The priest stands in the centre of a congregation not lined up in pews facing him, but gathered around him seated on chairs or squatting on the floor.

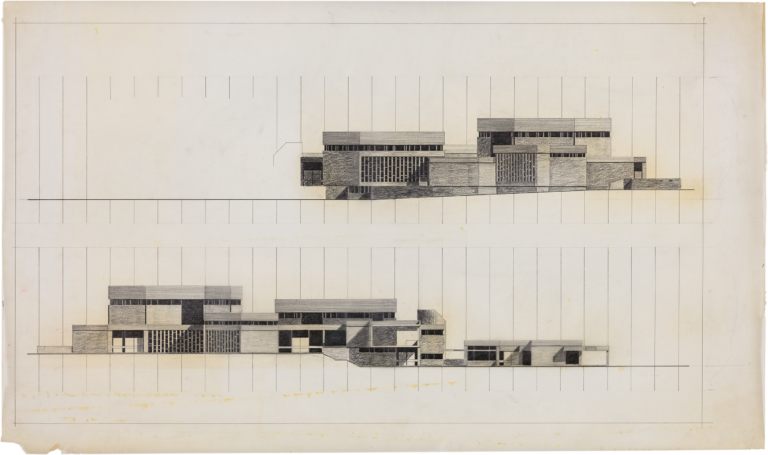

For this purpose, the altar with its simple substructure of squared timbers has the same design on all sides. On the off-form walls, lettering in different languages proclaims “Christ is risen”. The font typical of the time in combination with the longitudinal banner format is reminiscent of political rallies of the 1960s and 1970s and expresses the will for reform of the time. It was in this spirit that the church centre was also designed for the politically active congregations of both denominations, which took part in peace marches and campaigned for medical care in the neighbourhood. The aim was to counter the prevailing misgivings about the Church as an institution by adopting a new formal vocabulary. To this end, a customised architectural language with a recurring façade scheme was used, which in large parts barely distinguishes between church, retail, administration, cultural institution or leisure facility. This can be seen in grey-shaded elevation drawings of the community centre and the neighbouring Dortmund Scharnhorst Centre comprising shops, a swimming pool, comprehensive school and much more, for which the Werkgemeinschaft Gastreich, Gastreich-Moritz and Riepe drew up a surveyor’s plan from 1968 onwards. As can be seen from the plan documents, the community centre was also to become a natural part of the centre and the residential area in terms of the impression made by the buildings.

The restaurant

From the very beginning, the open and community-minded approach of the congregations also included hospitality, in order to facilitate informal gatherings as a continuation of the church service. Even today, the congregation and restaurant share a sign above the entrance, which was included in the planning as early as 1975. This juxtaposition of the lettering “Katholisches Franziskus Zentrum” and “Gaststätte Am Brunnen”, linked by the logo of a local brewery, testifies to the will to serve the people, far from any fear of contact. In the rooms of the restaurant, the congregation contrasted the austere simplicity and lack of ornamentation of the centre with a certain tavern romanticism by decorating the interiors with half-timbering, a historic-looking indoor fountain and wall paintings. As can be seen in the archive photo, the latter show important buildings in Assisi, the birthplace of St Francis. Decades later, the murals were replaced in the course of renovation, and the same artist, an active parishioner, again chose to depict Assisi, this time filling the wall. One can see the elevated forecourt of San Damiano, from which a (freely composed) panorama of the town of Assisi extends.

The window sill of the restaurant of the Franciscan congregation, which looks out onto unadorned exposed aggregate concrete façades, leads contrastingly from Scharnhorst to Assisi to the parapet of the central Italian convent against the spectacular backdrop of the medieval town. According to legend, St Francis was praying outside the ruined church of San Damiano in 1205 when God said to him: “Go and rebuild my Church, which is all in ruins.” As a result of this and other awakening experiences, St Francis committed himself to a renewal of the Church and chose to live a life of simplicity, dedicated to the service of others. Thus the depiction of San Damiano, on whose forecourt the artist has placed two people at the café table, serves not only to create atmosphere in the restaurant, but also to legitimise the location.

The present text was first published in: Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, Wolfgang Sonne, Barbara Welzel (ed.): Religion@Stadt_Bauten_Ruhr, Dortmund 2021, pp. 290–305.