Jewel of the North

Christin Ruppio“A jewel of the north that is as beautiful as it is expensive, the new building of the Natural History Museum is to sparkle and shine as early as next year.” Mayor Willi Reinke Back in 1928, a Dortmund newspaper article stated: “The Fredenbaum forest […] is, after all, the lung by which the whole of the north of our city breathes”. And this was not only true for the Dortmunders who lived in the north. More than a century before Dortmund’s Westfalenpark opened with the Federal Garden Show in 1959 and became a widely known attraction, the Fredenbaum was already an important local recreation area in the region. It is therefore not surprising that it was the destination of the city’s first tram line at the end of the 19th century and became a favoured location from the 1960s onwards in the debate about a site for the Naturkundemuseum (natural history museum), now known as the Naturmuseum (nature museum).

Steadily growing collection

In c.1900, when the Fredenbaumpark was being created, Dortmund’s natural scientific society was founded, with whose support the Naturkundemuseum was opened in Viktoriastrasse in 1912. Just two years later, however, the museum began to think about another move, as the collection had grown immensely, especially as a result of donations from the public. But it was not until 1931 that a new home for the steadily growing collection could be found in the city centre in Balkenstrasse (today’s Friedensplatz). During an air raid in the Second World War, a large part of this building burned down completely and 90% of the exhibits were also destroyed. Thanks to generous donations, however, it took very little time to rebuild the collection.

Improvements in the living conditions

After the war, this important collection of sensitive exhibits in a museum that had only been partially rebuilt amplified the call for a new building. As early as 1953, definite ideas were being aired, and the architects Mechtild Gastreich-Moritz and Ulrich Gastreich submitted their first plans for a new building. At the time, however, the plans were for a site in Rombergpark. The question of location – whether in Dortmund’s north or south – kept the city council busy into the 1970s. This lively discussion can be easily traced in the press review preserved in the Dortmund city archives. The articles from this period also reveal how much the residents of the Nordstadt were pressing for improvements in the living conditions in their neighbourhood.

Nordstadt

The Nordstadt – the northernmost inner-city district – had been heavily damaged during the Second World War and was noted for its high population density and a diverse neighbourhood. Key impetus for the intended regeneration of the Nordstadt came from the extension of Münsterstrasse, the street on which the Naturmuseum now stands. While some favoured Rombergpark in the south or argued that museums belonged in the centre of the city, the Social Democratic Party (SPD) campaigned for the museum to be built in Nordstadt.

Since at the time of the museum’s construction the Fredenbaumpark had one of the highest emission rates in the city – meaning that the air was anything but ideal for the sensitive exhibits – building at this location also meant higher construction costs for appropriate protective measures. The fact that the council nevertheless decided in favour of Fredenbaumpark in 1972 was an important pointer to the future prospects of the Nordstadt and represented an acknowledgement of the importance of cultural buildings for the city’s outward appearance.

Light-coloured natural stone

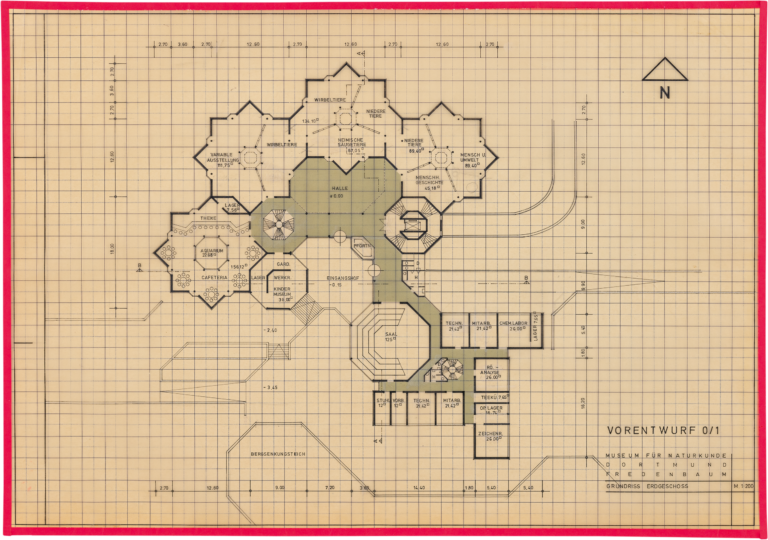

The husband-and-wife architects Mechtild Gastreich-Moritz and Ulrich Gastreich, who had previously submitted the earliest plans for a new building in Rombergpark, were invited to design the museum building in close consultation with the museum’s director Wolfgang Homann. Gastreich-Moritz and Gastreich created a building with a sculptural quality by designing a dynamic composition of squares and octagons set into each other in a stellar pattern. The north-eastern exhibition area is also easily identifiable from the outside by its jagged projections, while the administrative area in the south-west looks more discreet with its square rooms. The building’s sculptural look is also reinforced by the natural stone façade of gneiss quartzite. A refurbishment from 2014 to 2020 added new materials to the façade with an entrance area of glass and Corten steel. Gastreich-Moritz and Gastreich continued the idea of representing nature in the architecture’s materials by using light-coloured natural stone for the surfaces of the floors and staircases.

Dovetailing of the building with its surroundings

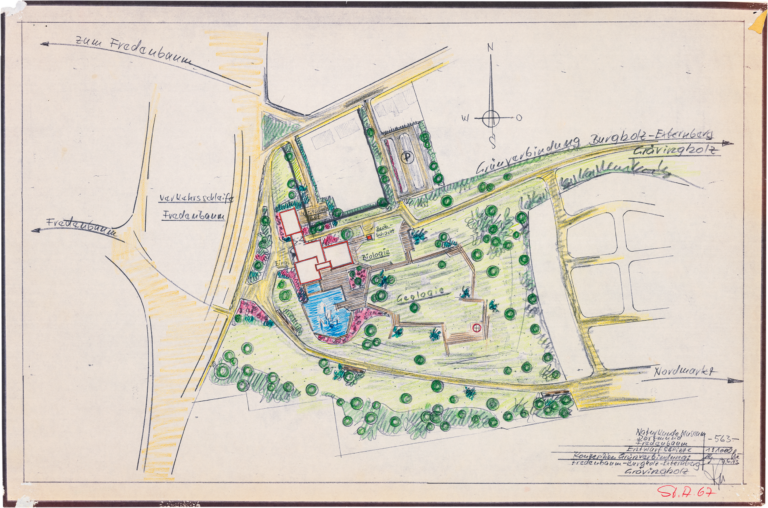

Between the exhibition and office sections is a lecture hall, the basement of which was designed as an outdoor space. This was a place to dwell on the walking path that led right across the site and at this point through the architecture. This opening has since been closed off, so that the notion of interlinking is now only visible on plans. The grounds were also designed by the architects. A design drawing for the green link from 1975 shows how the immediate surroundings of the museum building were planned – with an artificial pond, school gardens and exemplary greenery. Great importance was also attached to the transition to the surrounding park. If the ground plan of the building still looks different in this sketch and the entrance to the building is still further east towards Münsterstrasse – in the final design, the architects placed the main entrance towards the southern façade – one can already see that the idea of routing the walking path through an open basement already existed at this time. The dovetailing of the building with its surroundings was thus an important feature of the planning from the very outset.

Iguanodon in the atrium

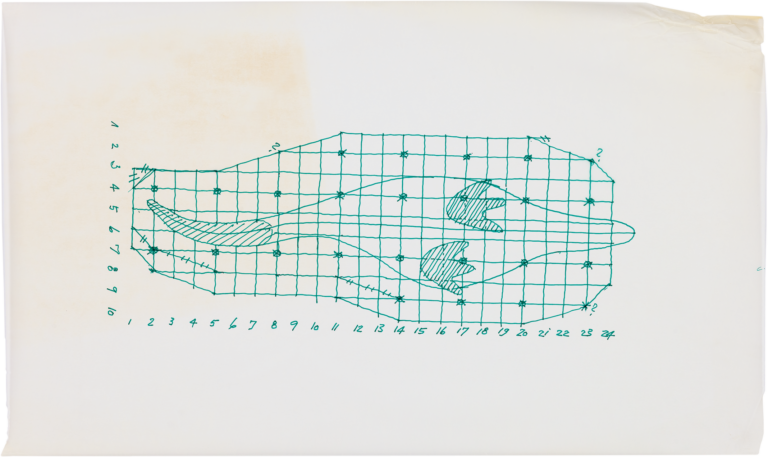

Inside, the rooms’ use of restrained materials allows the exhibits to catch the visitor’s eye. Since the museum’s opening, the life-size replicas of two dinosaurs made on site by the Italian animal sculptor Pietro Rabacchi have been a particular focus of attention. For the reopening of the Naturmuseum in 2020, the smaller dinosaur had to yield, as it no longer fitted into the museum’s new concept concentrating on regional flora and fauna. However, the large upright iguanodon spent the entire period of renovation under a tarpaulin and has kept his place in the atrium, as it has since been proven to have inhabited the region. The architects Gastreich-Moritz and Gastreich also already had to give consideration to this exhibit when designing the museum, as evidenced by some sketches from the Baukunstarchiv NRW. The drawings impressively illustrate the special tasks and challenges involved in designing a museum building.

Aquarium

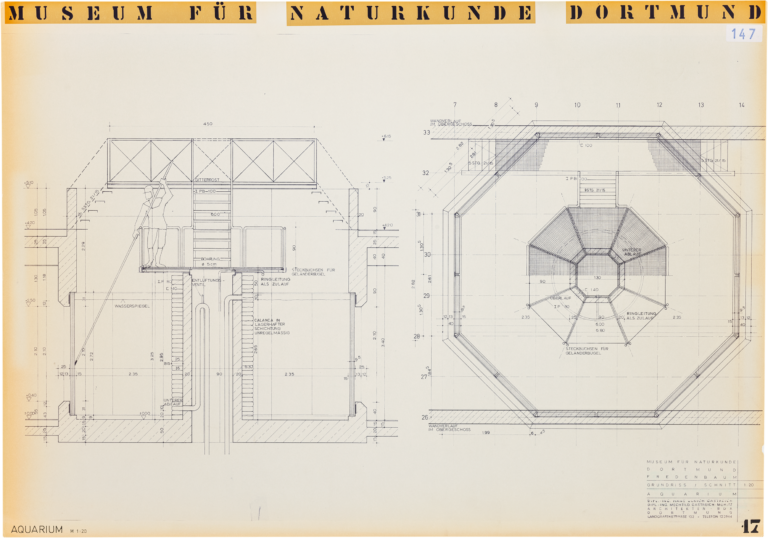

The architects had to find solutions for the display of a multitude of diverse exhibits – including the stability of a dinosaur model over five metres tall. Gastreich-Moritz and Gastreich also designed another of the museum’s crowd pullers, the aquarium. At the time of construction, it was a tropical freshwater aquarium with a volume of 73,000 litres. The octagonal tank 3 metres high and 6 metres in diameter was one of the largest of its kind in the Federal Republic at the time. The shape fitted into the compositional elements of the ground plan, while the column in the centre of the tank concealed all supply lines so as to create the appearance of a natural environment. As the aquarium began to leak after more than thirty years, it has since been converted into a 90,000-litre round tank. In line with the new exhibition concept, it is now home to fish from nearby Möhnesee lake.

Leisure destination for all residents

After only three and a half years for construction, the museum opened to the public on 24 May 1980. The opening event lasted six days and offered a wide range of activities for all age groups and interests. Since the museum was not targeted solely at an expert audience, but was intended as a leisure destination for all residents, this was a successful start. In addition to 10,000 citizens and the Lord Mayor, nature filmmaker Heinz Sielmann also turned up for the occasion. Sielmann was enthusiastic: “I don’t know of any museum on this earth where the citizen, the young person, can benefit so much in a short time as here.[…] I can only congratulate all those responsible and all the people of Dortmund for this.” To this day, the Naturmuseum is an important fixture in the network of cultural offerings and opportunities for leisure activities extending right across the city. Since reopening in 2020 – this time, owing to the pandemic, regrettably without a big celebration – the “jewel of the north” now shines with renewed lustre.

The present text was first published in: Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, Wolfgang Sonne, Barbara Welzel (ed.): “Und so etwas steht in Gelsenkirchen…”, Kultur@Stadt_Bauten_Ruhr, Dortmund 2020, pp. 150–163.