“No longer a trace of confinement”

Sonja PizonkaAt the end of the Second World War, the opera house in Essen (architect: Heinrich Seeling), which opened in 1892, was badly damaged, and the playhouse in Hindenburgstrasse was completely destroyed. From the 1945/46 season, the youth centre in Steele was used as a provisional alternative venue, joined later by the Saalbau Maas concert hall in Werden for opera performances. The two venues were located about seven and ten kilometres respectively from Essen’s city centre so “visitors could not be expected to travel the long distances” in the long run. Moreover, they were only suitable for theatrical productions to a limited extent.

Rebuilding

Artistic director Karl Bauer was constantly campaigning for a venue in the city centre, and after three years in Steele and Werden, even the construction of a temporary opera house seemed acceptable to him. He complained that good actors were avoiding Essen as a location: “We will have to resign ourselves to the fact that in a few years Essen will be bottom of the league in the theatre sector, because it will not be possible in the long run to keep top-level performers here, given the particularly difficult living conditions in Essen, as the city lacks the conditions for truly artistic work.” In the summer of 1949, the decision was taken to rebuild the opera house. The preserved scenery building and the only slightly damaged stage house were crucial to this decision, as it was hoped to cut costs under these conditions. The Essen architects Johannes Dorsch (1908–1976) and Wilhelm Seidensticker (1909–2003) were awarded the contract; no competition was held.

With its own distinctive character

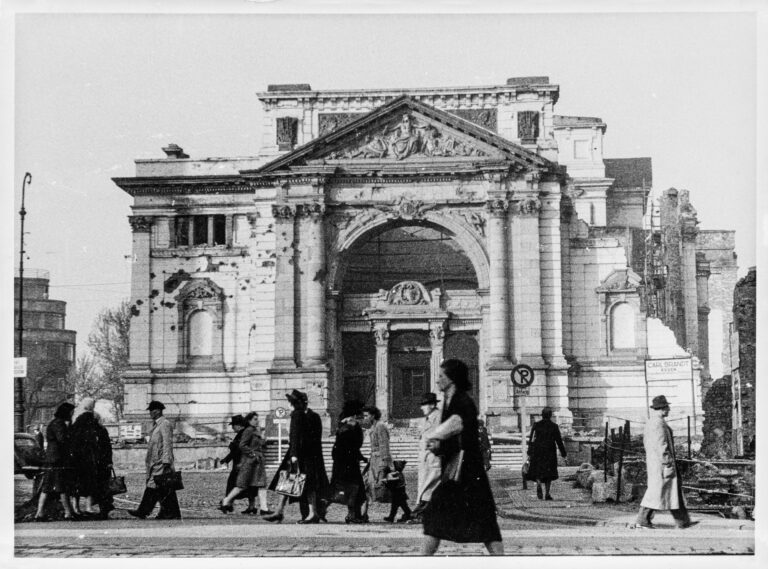

Wilhelm Seidensticker’s estate contains photographic documentation of almost every one of his building projects in a separate folder. The pictures were taken by a variety of photographers. The portfolio on Essen’s opera house, today known as the Grillo-Theater, contains photographs of the severely damaged building as well as pictures of the building under construction and in its finished state.

The rebuilding of the old opera house was not intended as an exact reconstruction of the original building. Dorsch and Seidensticker argued that, thanks to their design of the central section of the new entrance façade with its 17-metre-high pillars, the theatre would hold its own in its urban setting. And the local press also said: “The building must blend in with the neighbouring buildings, and especially the municipal office building and the future bank building on the northern side of the square. However, despite its integration, it had to stand out with its own distinctive character, which is all the more difficult because the neighbouring buildings, with their much greater height, easily overwhelm the architectural effect of the theatre’s frontage.”

Extension of the auditorium

Dorsch and Seidensticker not only created a new entrance façade, they also extended the theatre building as a whole by shifting the main entrance nine metres forward. They integrated the staircases, foyer and refreshment rooms into this stark and austere part of the building. The overall design, with its space-saving spiral staircases and low entrance area, was intended to permit an extension of the auditorium as well as to gain space for a lounge on the first floor.

An imposing hall with high ceilings

On completion at the end of 1950, the latter came in for special praise in the press: “There is no longer any trace of the confinement and oppressiveness characteristic of the old corridors and staircases due to their completely different design. An imposing hall with high ceilings opens up. The windows are tall and rectangular, the ceiling is vividly patterned, and the walls and curtains display in an intimacy of matching colours. Via four tall openings on the Kettwiger Strasse side, a festive room opens up that is also intended as the venue for the city’s receptions.”

Plans for a large opera house

However, from the 1951/52 season onwards, the number of 800 seats was already proving insufficient. During the official opening of the rebuilt opera house, building director Richard Rosenthal had already referred to plans for a large opera house with 1700 seats, which was to be given its place next to the theatre. It then took until 1959 until the “Gesellschaft zur Förderung des Essener Theaterneubaus” (Society for the Promotion of the New Theatre Building in Essen), founded four years earlier, announced a competition for this opera house. Although the plans of the competition winner Alvar Aalto were received with great enthusiasm, almost 30 years were to pass before the new opera house was be opened in 1988 (#Aalto-Theatre).

Rehabilitation work

By the end of the 1980s, the closure of the Grillo-Theater was under discussion. The building needed refurbishment because little had been done in this respect in the preceding decades; the repeatedly updated plans for the construction of the opera house to Alvar Aalto’s designs had led to several postponements of the necessary rehabilitation work. Hansgünther Heyme, artistic director of the Grillo-Theater from 1985, saw this as an opportunity to finally comprehensively modernise the building. The architect Werner Ruhnau (1922–2015) was commissioned with the upgrade and found in the Grillo-Theater a perfect example of the auditorium that he had been criticising for almost 30 years as unsuitable for modern theatre.

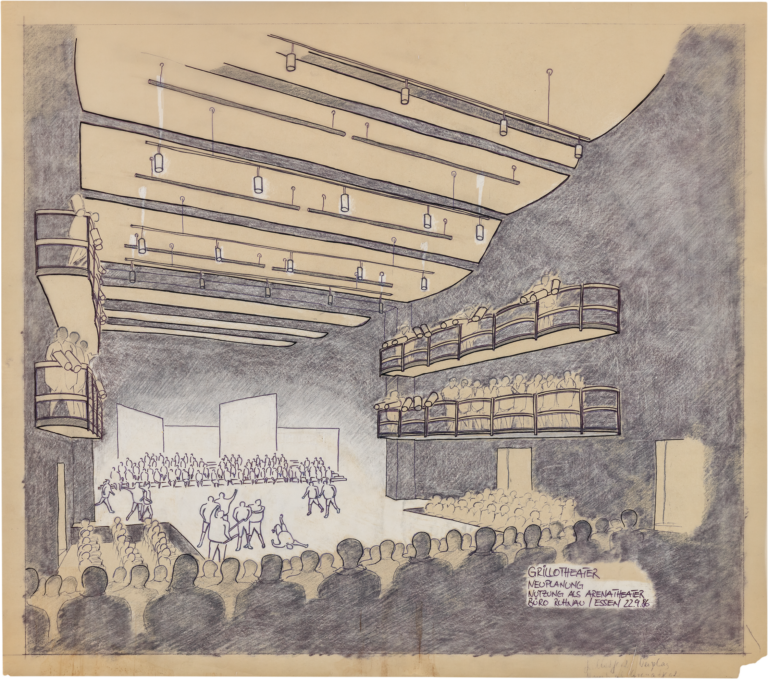

“Arena theatre”

Under the title “Existing, non-enlargeable stage opening”, he drew the existing spatial situation and contrasted it with conception of flexible theatre usage, in which the stage and audience seats can be reorganised to suit the situation. Under the title “Arena theatre”, he showed one of the various possibilities in which the action on stage was surrounded by theatre-goers. With his “holistic, contemporary understanding of theatre”, Ruhnau wanted to overcome the separation of performers and audience (#Musiktheater im Revier) , but also included traditional forms of presentation in this flexible approach: “In addition, of course, the old proscenium stage remains possible for historical repertoire.” However, the redesign made it necessary to reduce the number of seats to between 350 and 550, depending on the type of stage. And almost nothing remained of the theatre hall’s old furnishings after refurbishment. The stucco and chandeliers had been removed and replaced by highly visible lighting, sound and projection technology. The room now had “the character of a workshop theatre”.

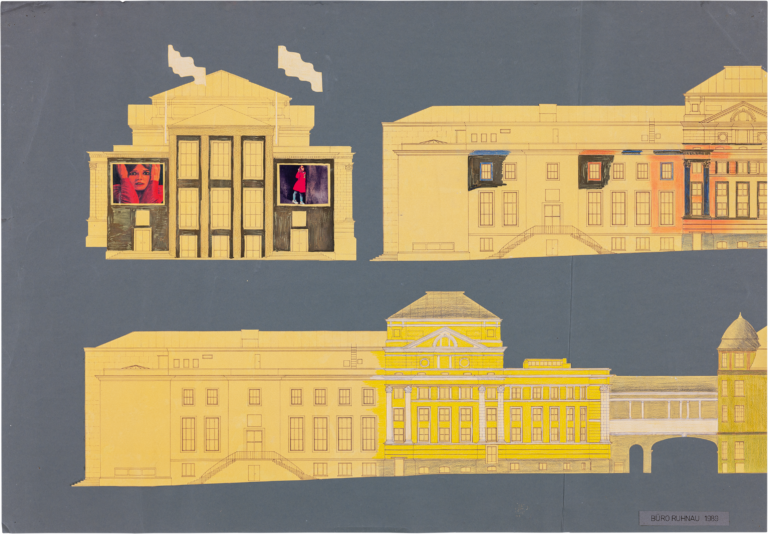

Pompeian red

On several large boards, Ruhnau tried out various colour schemes for the façade of the renovated Grillo-Theater. According to Ruhnau, the building has no need to not hide itself: “The exterior design of the theatre should attract attention, stand out from the grey drabness of its surroundings and be inviting. Colour of the exterior walls Pompeian red, projecting components light-coloured and preferably white. Capitals, cornices, friezes and classical capitals coloured.” Attention was to be drawn to the invigorated old theatre building with bright colour and large outdoor advertising, almost like the advertising strategies from the controversial US book “Learning from Las Vegas”. In his designs, Ruhnau therefore filled the large information areas on the theatre façade, which were already in place before the closure, with colourful photographs and drew on waving flags. In addition, he planned various signages that would draw attention to the new bookshop and the theatre café.

Colour dispute

The “austerity of form” and “dignified festive touch” of the main façade no longer featured in these designs; instead, the aim was to outdo the advertising of the inner-city shops. In the end, however, these designs were not realised in their entirety. The theatre was given the “Grillo-Theater” lettering, but the requested Pompeian red, which in the meantime had prompted a colour dispute, was not used. The building department favoured a rich red-brown, whereas Ruhnau and Heyme favoured the bright red. In the end, the theatre was painted in a less conspicuous light reddish brown and greyish white.

The present text was first published in: Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, Wolfgang Sonne, Barbara Welzel (ed.): “Und so etwas steht in Gelsenkirchen…”, Kultur@Stadt_Bauten_Ruhr, Dortmund 2020, pp. 238–251.