On the simultaneity of performance spaces

Anna KlokeIn a photograph taken in c.1960, a bright white showcase, expansive and strictly axially symmetrical in composition, contrasts starkly with the clouds of smoke from the chimneys on the horizon. While the Musiktheater im Revier is shown here from a bird’s eye view like a UFO that has just landed in the setting of an industrial city in the throes of reconstruction, the photographer’s view in the November 1959 issue of the Westfalenspiegel blanks out this framing. Against a bright sky, the theatre is staged here from the point of view of a stroller passing the symbol of the German economic miracle neatly parked outside shops. Only in the text is reference made to a supposed culture clash: with its theatre, the “City of a Thousand Fires” has “re-kindled its cultural will to live by adding a modern manifesto”. Where industries have combined in a “symphony of labour” and football and horse racing are at home, “now a worthy new abode is also being built for the Muses”.

Stages of the Gelsenkirchen

Having grown rapidly into a large city as a result of industrialisation and municipal incorporation, Gelsenkirchen had already been short of public cultural buildings before the Second World War, but makeshift stages in cinemas, restaurants and municipal institutions, among other places, provided opportunities for the unfolding of cultural life. There was also a stage for theatre performances in the new civic hall built in 1935, but it was destroyed during the war and was replaced in 1955 by a conversion of the concert hall in the Hans-Sachs-Haus.

In 1952, an expert opinion commissioned by the city for the construction of a new theatre emphasised the significance for the urban setting of precisely this brick building designed by the architect Alfred Fischer. On the basis of the expert opinion, the position of the new theatre in Florastrasse was therefore determined in a competition as an “urban hinge” between the Hans-Sachs-Haus and the Romanesque revival Georgskirche (St George’s Church) in Florastrasse. The initially unobstructed view of the Hans-Sachs-Haus from the glazed theatre foyer is documented in an archive photo. The picture turns the urban space into a proscenium stage. As if from a box seat, lined-up chairs specially designed for the building by the architect invite one to watch the drama unfolding in the street.

Building description

This deliberate staging of the simultaneity of performance spaces originates from the architect Werner Ruhnau, born in 1922, who was commissioned in 1955 to build the “Städtische Bühnen Gelsenkirchen” (municipal theatre), later renamed the “Musiktheater im Revier”.

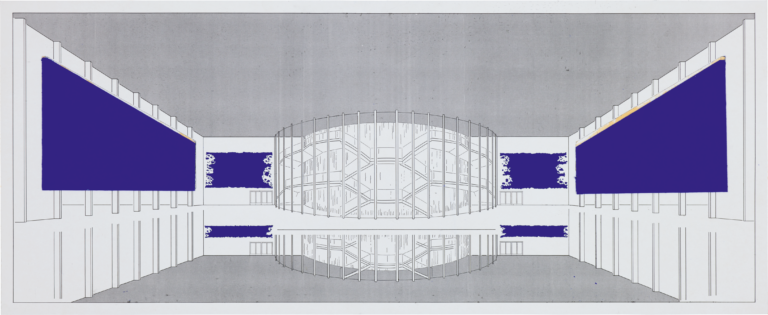

Next to the “Kleines Haus” (small house), which the Essen architect developed in a second competition stage from an outbuilding with a rehearsal stage, the so-called “Grosses Haus” (large house) forms the focal point of the ensemble with a square in front of it. The axially symmetrical, cuboid structure of the large house hovers on the entrance side above a recessed black-tiled plinth. The glass façade extends above it, enabling views inside the two foyers. These extend across the entire width of the façade and are separated from the auditorium behind by a white plastered rear wall with a central stair well rotunda. The entrance to the building is in a one-storey low building in front of it on the central axis, which has a sculpture by the artist Robert Adams right across its front. Surmounting everything is the box on the roof containing the catwalk and fly system, which had to be enlarged in the 2000s for technical reasons.

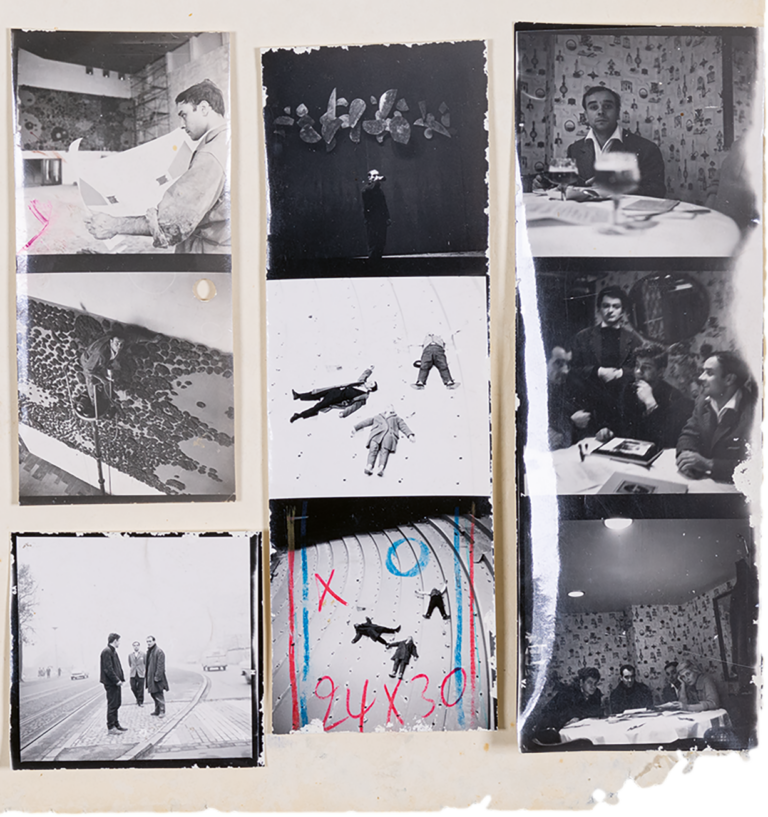

A two-storey, fully glazed bridge creates a link to the small house on the west side, which, in contrast to the three-tier auditorium in the large house with over 1000 seats, can accommodate only 336 visitors on movable seating. The block clad in grey natural stone slabs under a lead-surfaced roof seems to float on slim pillars above a recessed, glazed plinth. The intermission foyer on the first floor also has full-surface glazing overlooking Overwegstrasse. On the wall is an installation by the artist Jean Tinguely, which can also be seen in a photo collage by Ruhnau.

Special experts for aesthetics

The pictures literally tell of the interplay of those involved in the project. Ruhnau saw himself “as an intendant or director who creates a work in collaboration with visual artists and such specialists as structural engineers, craftsmen and acoustic engineers.” After a competition, an international group of artists was commissioned with the artistic design of the theatre in February 1958. The collage composed of contact prints conveys the impression of a building process whose peculiarity is also rooted in the temporary cohabitation of the artists on the project site, on the model of a medieval building lodge. Ruhnau’s “special experts for aesthetics” included the aforementioned Frenchman Jean Tinguely and the Briton Robert Adams, as well as the German artist Norbert Kricke, who created a relief on the outside wall of the small house. Coming from Berlin, Paul Dierkes designed the rotunda in the foyer of the large house. Pride of place was given above all to Yves Klein, who can be seen here engaged in collage on a lifting platform in front of his ultra-mini blue “reliefs éponge”. The glass façade of the large house is its display case, spotlighting the works of art, especially after dark. In this way, the art can be enjoyed not only the paying public but also by passers-by.

Homo ludens

Ruhnau was always keen to point out that the transparency of the building was not only intended as an expression of the democratic openness typical of the time, but also sought to continue the stage into the foyers and beyond into urban society for the benefit of the “homo ludens”. As stated in various manifestos and other publications, Ruhnau saw the theatre as a pilot run for new social interaction that should not only be visible in the city, but also be experienced. Thus, as already mentioned, the main building with its open foyers is deliberately designed as a window and showcase to the city.

With the help of one-point perspective, Ruhnau placed the theatre at the centre of a wider urban development in a drawn vision of the city in c.1960. The drawing illustrates the architect’s comprehensive design aspirations and epitomises his lifelong preoccupation with the building. He thus involved himself in debates on urban planning and was most recently commissioned with refurbishment work in partnership with his son Georg at the beginning of the 2000s. From the beginning, Ruhnau proactively pursued international public relations for the building, which was listed in 1997, and documented this for his own archive, which became the property of the Baukunstarchiv NRW after his death in 2018. His estate, remarkable in its scale alone, displays a huge diversity of media and reveals the Musiktheater as Werner Ruhnau’s key early work.

The present text was first published in: Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, Wolfgang Sonne, Barbara Welzel (ed.): “Und so etwas steht in Gelsenkirchen…”, Kultur@Stadt_Bauten_Ruhr, Dortmund 2020, pp. 28–41.