House of Culture

Sonja Pizonka“From now on, life at home and at work will be dominated by knowledge, education, learning and teaching.“ City of Gelsenkirchen

The certificate for the laying of the foundation stone for the Gelsenkirchen education centre (Bildungszentrum Gelsenkirchen) in 1968 begins with the preceding quotation and explains the decision to build it with the intention of it being “of benefit to the citizen for his development, to the community for progress, and to democracy”. This building, a centrally located institution for adult education (#Adult Education Centre), had already been demanded by the lecturers’ association for adult education in Gelsenkirchen in a letter to the city director in 1957: “Today, our adult education institution is one of the leaders among those in the German Länder. However, this reputation can only be upheld as things continue to develop if our own education centre, long proposed from various quarters, is realised in the foreseeable future. Such neighbouring towns as Dortmund, Marl and Oberhausen have already taken the lead in this area, so that our current leading position in the region is at risk of being eroded, if not lost.“

Makeshift decentralised solution

At the time, adult education courses in Gelsenkirchen were mostly held in the evenings in various municipal school buildings. The cycle of the school year also dictated the work of the adult education institution – the rooms remained closed during the school holidays and on public holidays. The lecturers wanted an end to this makeshift decentralised solution, citing a fine example in the immediate vicinity: “What such an education centre as a meeting place and open door can mean in terms of its human, spiritual and political impact is illustrated, for example, by ‘die insel’ in the neighbouring small town of Marl. This institution has become the centre of adult education for the whole community. It has become apparent that in its own building its work is not limited to evening classes, but extends to mornings and afternoons. Accordingly, adult education in Marl has experienced an unexpected boom.“

Not only classrooms

Germany’s first post-war centre for adult education was built in Marl in 1955 (architect: Günther Marschall); the building contained not only classrooms but also the municipal library with a magazine reading room. In Gelsenkirchen, too, the education centre’s room programme first had to be defined. The building project bore the working title “House of Culture”, as the planned new building was to house not only adult education, but also the municipal library and the municipal archives.

Development of the cultural institutes

To lend more concrete shape to their own plans, Gelsenkirchen’s civic leaders and the staff of the municipal library and adult education centre (Volkshochschule) gathered information on the development of the cultural institutes in neighbouring towns and cities. Director of the adult education centre Andreas stressed: “In terms of size and ambition, this institution […] should in any case – not least for reasons of our city’s reputation – be able to hold its own with the much-lauded Fritz-Henssler-Haus in Dortmund”. In Dortmund, the members of Gelsenkirchen’s administration and the cultural committee also visited the “House of Libraries” (#House of Libraries) at Hansaplatz (1958, architects: Walter Höltje, Karl Walter Schulze) at the end of 1963. This building was shared by various institutions, in this case the public library, the more academically oriented municipal and Land library and the Institute for Newspaper Research. Fritz Hüser, head of the public library, advised the visitors to plan generously and with an eye to the future, because the subsequent incorporation of the children’s library had resulted in space problems in Dortmund. In the original plans, it was assumed that the city centre would not be suitable for children because of the “traffic hazards”, so children’s literature was initially omitted.

Adult education building in the city centre

In addition to the room programme, the location of the education centre was also discussed at length. In their letter of 1957, the lecturers favoured a green site near the city centre, similar to “die insel« in Marl; they therefore suggested the Stadtgarten park as its location (#Josef Albers Museum Quadrat). However, there were also voices critical of the idea of an adult education building in the city centre. The Buersche Zeitung, published in the northern district of Gelsenkirchen-Buer, argued in favour of retaining the concept of many smaller locations and flatly rejected the idea of combining the adult education centre and the municipal library in a single building: “The municipal library cannot be centralised at all; it has to go to its users.” That’s why it makes sense, “as various banks do, to spread its branches as widely as possible.” Library users and course participants should be spared long journeys, it said.

Close to the new theatre

But the centre of the city was changing. In 1959, the new Musiktheater (music theatre) opened on the northern fringe of the city centre (architect: Werner Ruhnau). This new and internationally acclaimed building showed that post-war Gelsenkirchen was a city on the ascendant (#Musiktheater im Revier). In 1960, Lord Mayor Hubert Scharley therefore insisted that the combination of library and adult education centre absolutely had to be built in the vicinity of the Musiktheater. The minutes of the cultural committee stated that “the erection of a separate building […] in the forum of the city, close to the new theatre, was vital.” In the ideas competition for the design of the theatre forecourt, the location of the education centre was decided in 1962. The Münster architect Harald Deilmann (1920–2008) won second prize in this competition with his forecourt design and was immediately commissioned with the design of the education centre.

Redevelopment of the northern area

Prior to that, Deilmann had successfully participated in two other competitions for this location: 1954 with Werner Ruhnau, Ortwin Rave and Max von Hausen as the team of architects in the competition for Gelsenkirchen’s new Musiktheater building and in 1961 in the competition for the building of the Metal Vocational School (now the Vocational College for Technology and Design) to the north of the Musiktheater. The school built to his design then opened in 1968. The press welcomed the redevelopment of the northern area of the inner city. At the start of work on building the education centre, it was said: “The new project will be another step towards the finalising the arrangement of buildings flanking the theatre forecourt (the public baths, police station and an insurance building will also be erected). By then, the city centre will have changed beyond recognition.“

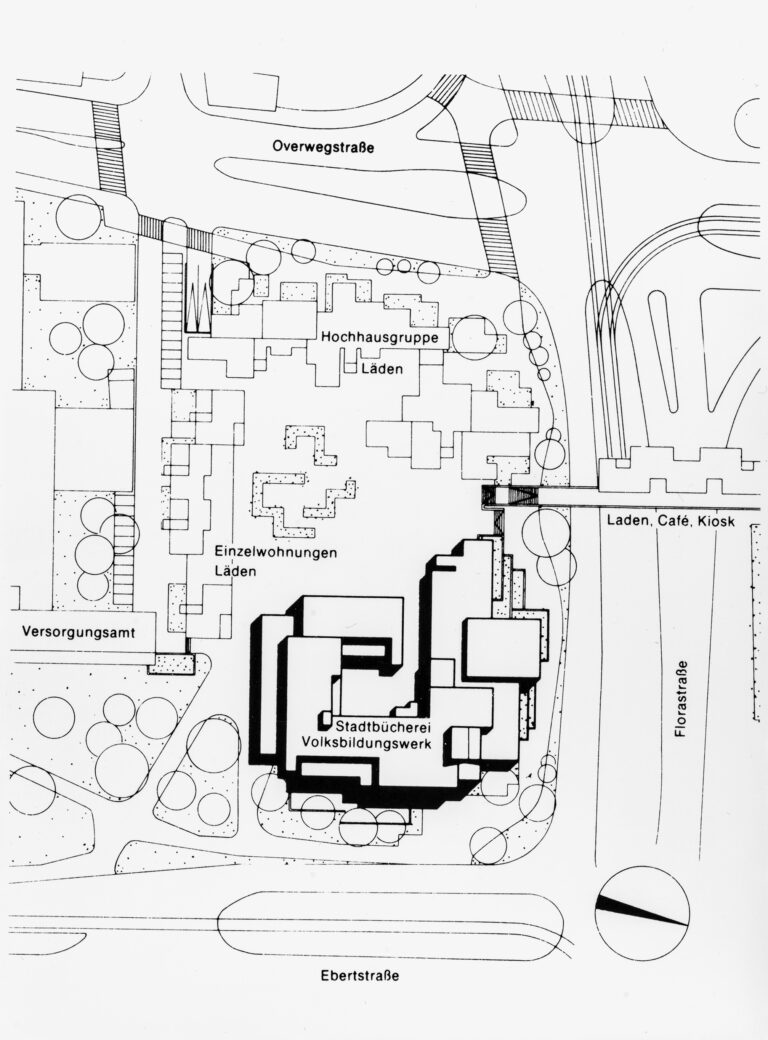

Junction of Florastrasse and Ebertstrasse

Deilmann started designing the education centre in 1966 and conceived an architecture that would include rooms for the library, municipal archives and adult education centre as well as various offices and service rooms for the administration. Although the building site for the new education centre was opposite the Musiktheater, they were separated by the busy Florastrasse. This location right beside a major thoroughfare prompted Deilmann to organise the building around a sheltered courtyard. He noted: “The location’s siting at the busy junction of Florastrasse and Ebertstrasse prompted the development of an introverted building form with its back turned to the sources of noise, which, on completion of the adjoining buildings, will be accessed via a courtyard.” To enable pedestrians to cross Florastrasse without encountering motor traffic, early plans also envisaged a footbridge with shops, cafés and a kiosk that would provide a link to the Musiktheater. However, this bridge structure, for which Deilmann drew inspiration from the famous Ponte Vecchio in Florence, was never built.

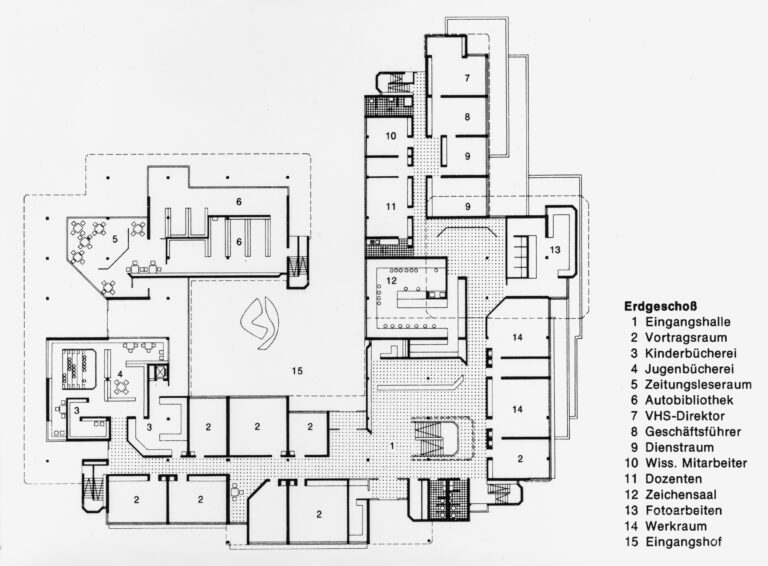

Language laboratory and “library on wheels”

The education centre opened on 21 January 1972. Here, the building’s façade clad extensively in roof slate contrasted with the neighbouring Musiktheater with its glass frontage. Deilmann cited pragmatic reasons: “Given the high levels of air pollution, this cladding provides a practical weatherproof skin.“ The building with its underground car park housed the adult education centre and the municipal library with the affiliated municipal archives as well as the offices of the culture department and the general music director. On the ground floor, accessible to visitors from both Ebertstrasse and the courtyard, were the foyer, children’s and youth library, newspaper reading room, lecture and work rooms, and language laboratory. In the language laboratory there were places for 28 course participants who could learn foreign languages under guidance with the help of sound recordings. On the west side next to the entrance to the inner courtyard was also the entrance to the mobile library, a “library on wheels”, that brought the lending service to various locations in the city. From the entrance hall on the ground floor, two staircases illuminated by custom-made “lamp trees” led to the upper floors.

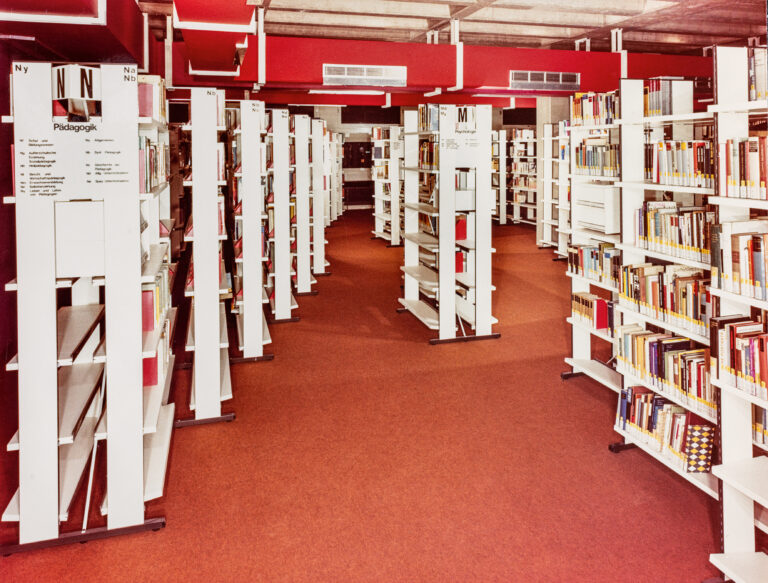

Events and exhibitions

Coffered fair-faced concrete ceilings and bare concrete columns in combination with brick floors on the ground floor and cognac-coloured needlefelt on the upper floors dictated its appearance. Supply and exhaust air installations remained visible and were painted in different shades of red. The entrance hall and the open shared space on the upper floor could also be used for events and exhibitions. The building housed the open-stack and music library as well as a television room, directing and recording areas, and a lecture theatre with seating for over 170 people and a demountable stage.

Cultural centre

In 1997, to mark the 25th anniversary of the education centre, an exhibition took a look back – not only at the preceding quarter of a century, but also at the very first competition on the site. For there, on what was then called the “meadow”, a competition was announced in 1919 for the design of a cultural centre with a “House of Art”, “House of Education” and “House of Labour”. Hans Scharoun also submitted a competition entry under the title “Man is Good”. Due to the economic circumstances at the time, these plans were shelved. Instead, it was to take more than fifty years before literature and educational opportunities along with theatre found their place in the northern part of Gelsenkirchen’s city centre.

The present text was first published in: Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, Wolfgang Sonne, Barbara Welzel (ed.): Bildung@Stadt_Bauten_Ruhr, Dortmund 2022, pp. 342–357.