Referencing the outside world

Christin RuppioWhat do Bottrop’s Stadtpark (municipal park) and Yale University in New Haven have in common? They are the two places in the world to visit if you want to explore the work of Josef Albers (1988–1976). Albers – incumbent of various positions at the Bauhaus from 1923, and its deputy director from 1932 – fled Germany for the USA as early as 1933 accompanied by his wife Anni, also an artist at the Bauhaus. In 1979, Anni Albers and the Albers Foundation donated 91 paintings and 234 prints to the city of Bottrop. The artist’s home town thus preserves almost his entire graphic art oeuvre and the world’s largest Albers collection.

Head of the building department

The place where this important collection is preserved and exhibited was designed by the architect Bernhard Küppers (1934-2008). As head of the building department of the city of Bottrop, Küppers attached great importance to being creatively involved in design work. During his 10-year tenure, Küppers added 35 urban buildings to Bottrop – an extensive legacy of urban design, some of which is now threatened with demolition. The Museum im Stadtpark thus not only preserves collections, but is also the work of an architect who played a major role in post-war urban planning. The architect’s estate is preserved in the Baukunstarchiv NRW.

Spaces and people

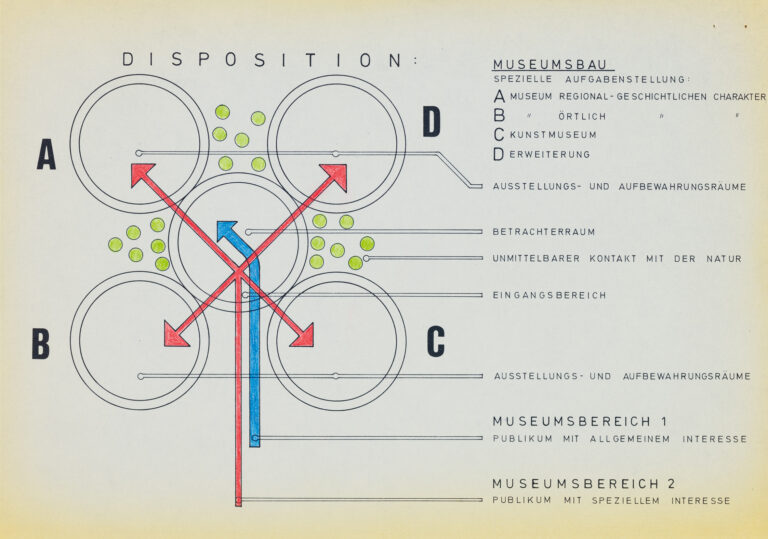

This collection of numerous sketches, drawings, photographs and texts illustrates how Küppers approached the museum project in great depth and from multiple perspectives. Included, for example, are a large number of small-format sheets of sketches in which the architect explored the spatial arrangement, as well as a theoretical text on the expectations of new museums, to which Küppers added diagrams on sensible visitor routing in his museum. Küppers’ legacy on this project shows an insistent inquiry, characteristic of the post-war period, into how spaces and people interact.

Local history collection and Albers paintings

The first post-war exhibition of Albers’ works in his home town was privately organised in as early as 1958. Albers subsequently donated six paintings to the town, prompting it to consider building a museum. It was decided to add a spacious extension to the already existing museum of local history. This is why the “Quadrat”, which opened in 1976, proved to be an exciting combination of a Wilhelminian-style villa to which Küppers attached three square pavilions of equal size in a steel skeleton construction. Built in 1903, what was once the official residence of the magistrate was actual due for demolition in 1960, but was instead converted into a local history museum with a collection of mammoth skeletons as its special attraction. The extensive collection and especially these monumental exhibits soon highlighted the need for a larger exhibition space. An appropriate exhibition space for the local history collection and the first Albers paintings donated to the town was found on a single site. Despite the very limited financial resources, a museum centre was to be established here to accommodate a rather unusual collection of objects and thus also be a place for comprehensive cultural education in a museum setting.

“Homage to the Square”

According to a booklet issued for the opening of the museum: “The ‘square’ has an active meeting place: the action space. […] a very lively meeting place: the Museum für Ur- und Ortsgeschichte (museum of prehistory and local history). […] a colourful and stimulating meeting place: the Moderne Galerie (modern gallery).” Küppers housed these three quite different requirements – a modern art exhibition, a media centre with space for events and a place for learning about local history – in three square pavilion buildings of equal size. The arrangement of the three building elements allows views from the gallery via the media centre into the Ice Age hall containing the mammoths, a fluid experience of space.

Although the bulk of the collection of visual art at the time did not consist of works by Josef Albers, both the name of “Quadrat” and its implementation as a multi-faceted place of learning suggested a reference to Albers’ Bauhaus teachings and his work as an artist. Without wanting to force a comparison, links can be found between Albers’ work and Küppers’ approach. Albers varied the square in his famous series “Homage to the Square” for over a quarter of a century. And from Küppers’ sketches we can also see that he developed the museum building from the geometric form of the square from the outset.

Interrelationship

While the interaction of colours is a prominent theme in Albers’ famous Square series, Küppers addressed the interaction of art and environment, interior and exterior space in his architecture. Consequently, Küppers also helped design the surrounding greenery and paths in the Stadtpark. In photographs from the time of its creation, it is very easy to see how the extensive glazing creates a transition between interior and exterior. The gaze can wander over the sculptures in the gallery into the park, and glimpses of the museum are also possible from the outside. The interrelationship between interior and exterior is further intensified by the sculptures located in the park. In this way, people walking in the Stadtpark can also share in the experience of the “Quadrat” as a meeting place without entering the building.

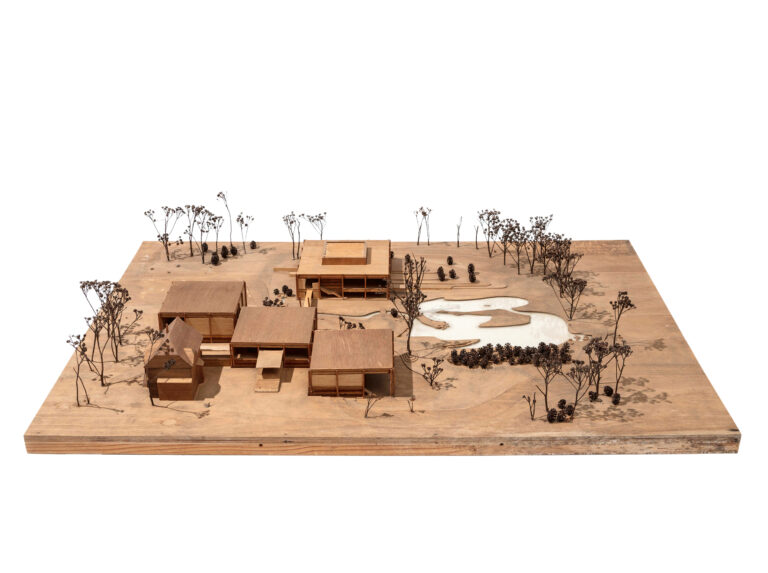

Plans for an Albers museum

When Anni Albers made a substantial donation from the estate of her recently deceased husband in 1976, it became clear that the “Quadrat” needed another extension. Interestingly, sketches from 1974 – three years before Anni Albers first approached the town with her proposal – show that the option of an extension was already being aired at the time. When the plans for an Albers museum were fleshed out, however, Küppers stressed that it should not be a mere annex, but a building with an impact of its own. Thus, the Albers Pavilion is situated somewhat removed from the three clearly interconnected pavilions of the “Quadrat” and yet linked to them by a bridge. A wooden model from the Küppers collection – whose materiality reflects the project’s proximity to nature in a special way – gives an impression of the relative positions of the various pavilions and their interaction with the park landscape.

Meditative atmosphere

The Josef Albers Museum opened in 1983; exactly 50 years after Anni and Josef Albers fled from the National Socialists to the USA. The entire complex is thus significant not only as a high-quality post-war International Style building, but also as a gesture visible from afar: although the artist vilified by the National Socialists only returned from exile to Germany for visits, his works had now found a permanent home in his home town.

For the opening of the Albers Museum in 1983, Küppers wrote that Albers’ art needed rooms that had a meditative atmosphere but did not turn its back on the outside world. Küppers situated smaller, semi-open rooms around a larger main hall, which he created by inserting wall slabs. These cabinets are suitable for the presentation of smaller works and especially graphic art. Although it was not possible to design this part of the museum as openly as intended, to protect the graphic works in particular from excessive light, Küppers also attached great importance here to the integration of daylight and openings onto the park.

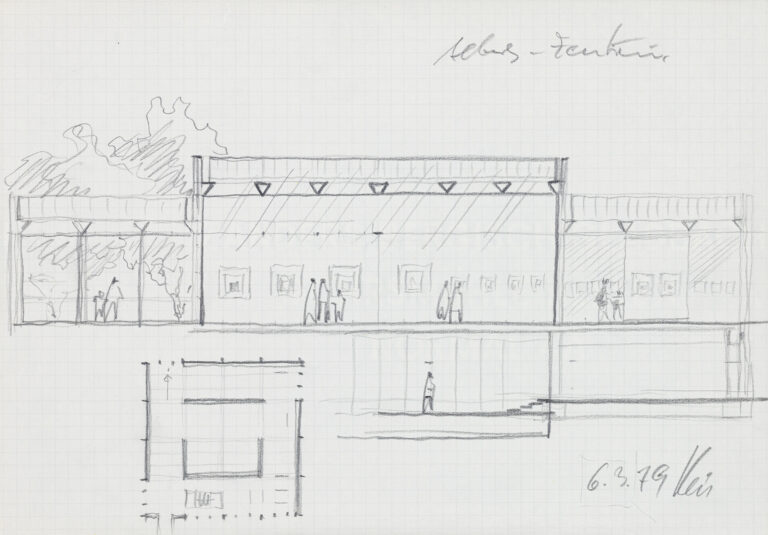

Lights

Light is an important factor for any museum, but for the exhibition of Albers’ work, the play of light on surfaces is of crucial interest. In some sketches for this project, Küppers explored the scope for opening up to the outside space and admitting light via sawtooth roofs, which he ultimately put into practice. In addition to this natural lighting from above, Küppers had additional fluorescent tubes installed on the undersides of the roofs for uniform artificial lighting. Küppers pointed out that Albers himself had used this light source when painting. The direct incidence of light via a number of large window openings – which were essential for the connection to the surroundings – can be regulated by louvres, as on the other pavilions.

Extension

Küppers succeeded in reconciling very different requirements in this museum complex, and he created an architecture that opens up and, through its modularity, invites extension. And so the “Quadrat” continues to grow, now with the participation of the next generation of architects. In 2020, an extension to the south-west of the Albers museum was built by the architects Gigon/Guyer. This extension is also accessible via a bridge so that all the squares remain interlinked.

The present text was first published in: Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, Wolfgang Sonne, Barbara Welzel (ed.): “Und so etwas steht in Gelsenkirchen…”, Kultur@Stadt_Bauten_Ruhr, Dortmund 2020, pp. 134–149.