Expression of the cultural will of a great city?

Anna KlokeIn the archive photograph, the architecture is assembled like a stack of building blocks, its rigour reinforced by the continuous joint pattern of an exposed aggregate concrete façade. Windows flush with the façade underline the structure’s three-dimensionality, emphasised further by the shadows captured in the photograph. The soberness of the impression is broken up merely by the occasional plant projecting above the parapet walls. The building traces the terrain sloping down to the north in a step-like manner, thus creating terraces. On the street side, the building opens up with concrete columns and thus defines an entrance area. The white-painted reinforced concrete parapet elements of the noise-abatement and solar-protection balconies stand out against the exposed aggregate concrete façade. Here, too, the play of light and shade enhances the dramaturgy (#University Library Bochum). The surrounding grounds are designed with nested, flat fair-faced concrete elements. A well-placed sign draws attention to the use of this multi-faceted building complex as an adult education centre (Haus der Erwachsenenbildung).

The history of the VHS Essen

As early as 1919, with the support of the then Lord Mayor and later Reich Chancellor Hans Luther, the Essen adult education centre was founded, initially housed in the Grillo-Haus at Burgplatz and later in the Keramikhaus am Flachsmarkt. According to the charter of the new educational institution, the aim was to “educate people to true nationhood, joyful public spiritedness and noble humanity, […] to introduce them to the context of world events and thereby make their occupational work joyful and valuable”. After its closure by the National Socialists in 1933, in 1946 – a year after the end of the Second World War – the British Military Government granted the application of the city of Essen to reopen the adult education centre, so that classes could be provisionally resumed in various public buildings.

The competition

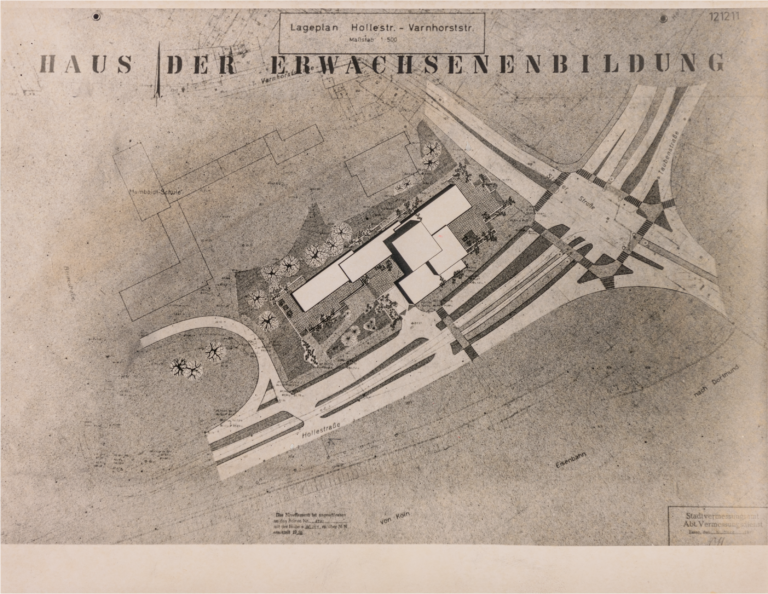

In 1962, the city council decided to erect the adult education centre building, which would also house the administration and business academy. Three years later, a competition was held among five invited architects and Holleplatz, “one of the most welcoming spaces in Essen’s city centre”, was chosen as the site. The site plan from the competition demonstrates the property’s convenient city centre location not far from Essen’s main railway station on Hollestrasse/corner of Steeler Strasse, the latter being one of the city’s main traffic arteries. Since none of the submitted designs was entirely convincing, the decision to omit the first place and award a second prize to Wilhelm Seidensticker (1909–2003) and a third to Heinz Budde (1924–2008) secured negotiation leeway for the next steps. The department of urban development expressed the wish to erect a building in such a prominent location as the “prelude to giving Essen’s city an interesting overall appearance”, creating “an energetic and distinctive landmark”. For this reason, the jury together with the Lord Mayor favoured Seidensticker’s design, which, with a “lively and exciting interplay” of building masses, surmounted by a seven-storey main structure, was convincing above all as an urban structure, but also from an economic point of view. Because of its positive functional and pedagogical features, Budde’s design, on the other hand, went down well with the culture working group, the then director of the adult education centre, Wilhelm Godde, and the head of the building department, among others. In the course of the negotiations, the room programme had to be adjusted due to financial difficulties and the additional inclusion of the Institut Français.

Finally, in 1967, the two architects were commissioned to submit a joint design plan, on the condition that the building be erected in two stages for reasons of financial affordability. Thus, the adult education centre areas with provisional rooms for the Institut Français were built first, from 1969 to 1971. In the second stage, the lecture halls of the academy and the Institut’s final rooms were then built. The high-rise building, previously lauded as a landmark feature and strikingly depicted in Seidensticker’s competition entry, was omitted. Nevertheless, at the topping-out ceremony for the second phase of construction in 1974, the Lord Mayor Horst Katzor, during whose term of office the 106-metre towering town hall was also built, praised the skeleton construction of precast reinforced concrete elements as a “functionally and aesthetically convincing expression of the cultural will of a great city”. Such an exemplary building in the heart of the city helped to democratise education, science and culture, he claimed. “It is precisely those people who, after attending in some cases miserable youth schools, now want to continue learning as working people, who, in the spirit of social democracy, have a right to state-of-the-art conditions for further education,” said the SPD politician. The building expresses the “importance of modern adult education” and “our city’s commitment to education” in the best possible way. We have taken a good step forward “on the way to a humane city […] by continuing the construction of this building”, said Katzor. The city of Essen wanted to create an “architectural atmosphere of freedom and playful surprise”.

Building description

In fact, the building, designed in the spirit of “democratic construction”, with its projecting terraces always permitted new inward and outward vistas, depending on the angle of view. Most of the 30 or so study rooms opened out onto roof terraces. A painting studio with a roof garden and a modern language laboratory were also included in the programme. Openly designed floor plans with mezzanines permitted exciting sight lines and, above all, participation in what was going on. The desire for the democratisation of education, science and culture found particular expression in the design of the “Forum for Cultural Manifestation”, the “centrepiece of the entire complex”. As can be seen from the ground floor plan and various archive photographs, the forum opens onto the foyer, the cafeteria and, via full glazing in the outer wall, also onto its surroundings. In addition, freely positionable seating was deliberately chosen here, as opposed to seating frontally facing a raised podium. Instead, in order to create a communication situation, rows were arranged around corners, forming steps down to a moderation area (#University Library Bochum). A wall relief, side tables with ashtrays and the provision of low, leather-covered armchairs communicated both quality and a certain conviviality. The wall and ceiling design highlights the grid not only as a structural feature (structural grid 4.80 × 7.20 metres generated from the basic grid of 1.20 × 1.20 metres), but also as one of the building’s design features, both externally and internally. Accordingly, the photographer captured the modern swivel chairs at the bar all facing exactly the same way and the ashtrays on the cafeteria tables arranged at exactly the same distances apart. The photographs, which were published in numerous (professional) journals, could just as easily depict the conference area of a business enterprise and convey to the viewer in their portrayal of order, earnestness and a certain elegance the importance of adult education for town and country at that time.

Reactions to the new building

In his speech at the topping-out ceremony in 1974, Werner Morgenstern, chairman of the city’s culture committee saw “that the time has now come to harmonise economic and cultural policy considerations in the evaluation of urban development.” The equipment and furnishings were considered exemplary among professionals and boosted the existing demand for adult education at that time. The Land government praised the building as exemplary and in 1974 even declared it the model adult education centre of the Land of North Rhine-Westphalia. This was underlined by a subsidy covering 50 per cent of the building costs for the second stage of construction, the pro-rata financing of the fittings and furnishings to the tune of DM 300,000 and the funding of further teaching posts. In the same year, North Rhine-Westphalia passed its “First Act for the Regulation and Promotion of Further Education in the Land of North Rhine-Westphalia”, which defined further education as the fourth pillar of the education system and elevated its promotion to a municipal duty. Many new institutions for further education were established as a result. The Heinrich Thöne Adult Education Centre in Mülheim was then built in 1979 by Dietmar Teich to a competition design by the architects Seidensticker-Spantzel-Teich-Budde-Gutsmann-Jung. Its terraces, among other things, are reminiscent of the Essen House of Adult Education and was listed for protection as a monument in 2015.

Demolition and new construction

In Essen in the 1990s, the House of Adult Education was found to be contaminated with health-hazardous PCB. The cost of remediation was put at seven million euros, as opposed to two million euros for demolition. Finally, in 2000, the city decided to build a new adult education centre at Burgplatz. The school building designed by Hartmut Miksch, with its glass curtain façade adjoining the historic Lichtburg film theatre, opened in 2004. The Haus der Erwachsenenbildung fell visibly into disrepair and stood out in the heart of the city as a supposedly off-putting example of 1970s architecture until it was completely demolished in 2014. For years now, there has been a large gap in what used to be the reception room of Essen’s city centre.

The present text was first published in: Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, Wolfgang Sonne, Barbara Welzel (ed.): Bildung@Stadt_Bauten_Ruhr, Dortmund 2022, pp. 308–323.