Light in the darkness

Anna KlokeThe career of architect Josef Franke (1876–1944) was shaped by two world wars, the Ruhr uprising and the Great Depression. His estate is one of the most personal collections in the Baukunstarchiv NRW. In addition to design documents, photographs and various publications, the family also entrusted the Baukunstarchiv with such personal documents as letters from the front, letters of condolence and medical records.

Press review

When Wattenscheid-born Franke died in January 1944, obituaries for him appeared in such regional newspapers as “Der Mittag” and the “Rheinisch-Westfälische Zeitung”, highlighting the significance, abundance and versatility of his work, especially for the Ruhr region at that time. In addition to private houses, residential and commercial buildings, housing estates, schools, and administrative and industrial buildings, Franke achieved regional fame primarily through his churches. Franke, strong “both as an inventor and in finding practical solutions to the tasks constantly arising in the industrial area at that time”, “brightened up the gloomy and dreary façades of industrial towns” with his buildings, according to “Der Mittag”. He invented building concepts and layouts that were “based on a sound perception of what is necessary and what is possible, of the intended purpose of the local context and, first and foremost, of the overriding sense-imparting idea”. In 1929, the Heilig-Kreuz-Kirche (#Church of the Holy Cross) in Gelsenkirchen-Ückendorf, probably Franke’s foremost work, was built in the style of Brick Expressionism. The Gothic sense of form, which was actually “doomed in an industrial town”, made its breakthrough with this building in particular, said the obituary.

Shortly after the completion of the Heilig-Kreuz-Kirche, Franke was commissioned by Franciscan nuns to build the Lyceum Aloysianum secondary school with a study institution in Gelsenkirchen-Bulmke-Hüllen.

The structure of the Aloysianum

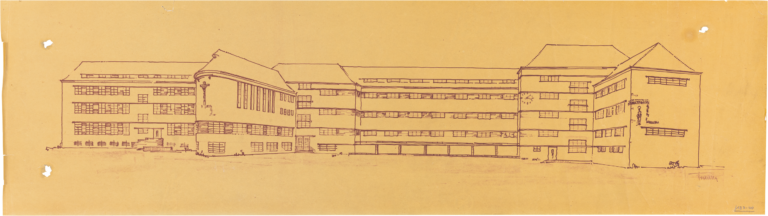

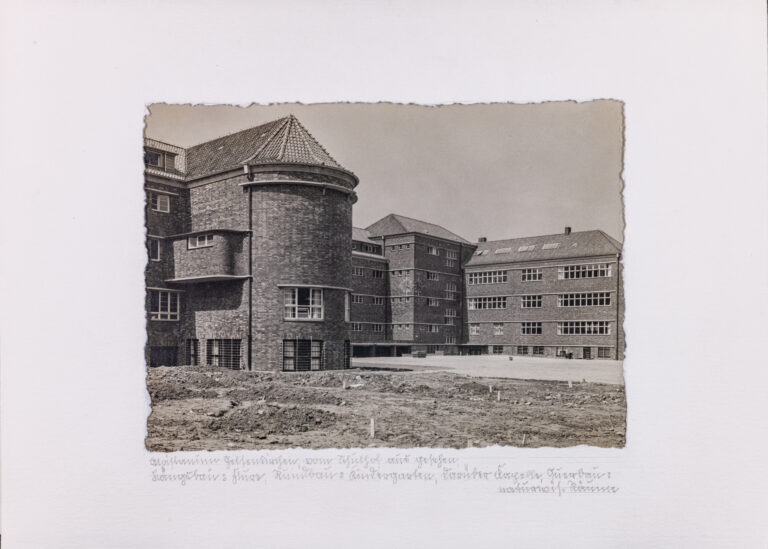

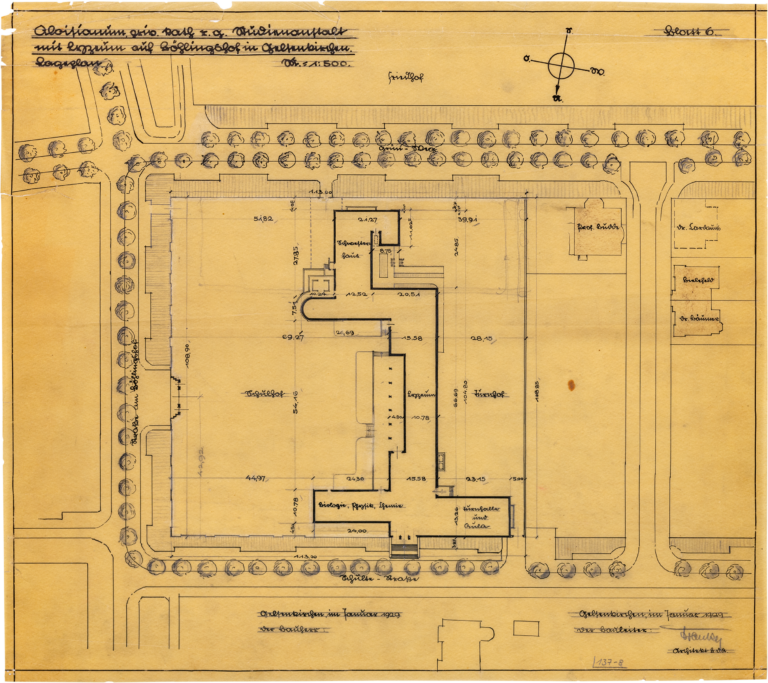

Looking at the site plan of the school building completed in 1931, one can see a regularly rectangular plot on which a richly structured, asymmetrical ground plan has been laid. It divides the 12,000 m² site into a playground and a gymnastics yard. Franke structured the building primarily according to its functional requirements. For example, the location of the classrooms in the central long building was intended to protect pupils from glare from the sun. On the ground floor, six columns mark a recessed break hall, from the roof of which the teaching staff were to supervise breaks in the playground. Adjacent to the long building overlooking Schultestrasse is a transverse building that houses the assembly hall and the gym in addition to the halls for the natural sciences, in a slightly offset alignment. Franke located these areas, which were also frequented by the public, in immediate proximity to the entrance from the road. The sisters’ house is located overlooking the local community cemetery on the opposite side of the school grounds, connected to the central school building via a wing that opens into an apse. This is where the school chapel designed by Franke was housed. In a perspective drawing of the courtyard, one can see how the various blocks of the building derive their identity from differences in height and in projecting and recessed building sections. The chapel is identifiable as such not only by virtue of its rounded roof and wall, but also by an appended cross and large upright window openings. Continuous cornices of sandstone accentuate the horizontal and unite the various façades into a single entity. Squat rectangular mullioned windows adjoin the cornices or are framed by them. The light sandstone bands contrast with the dark brick, an inexpensive building material that resists industrial gases and was chosen to make the building blend in with the houses in its surroundings.

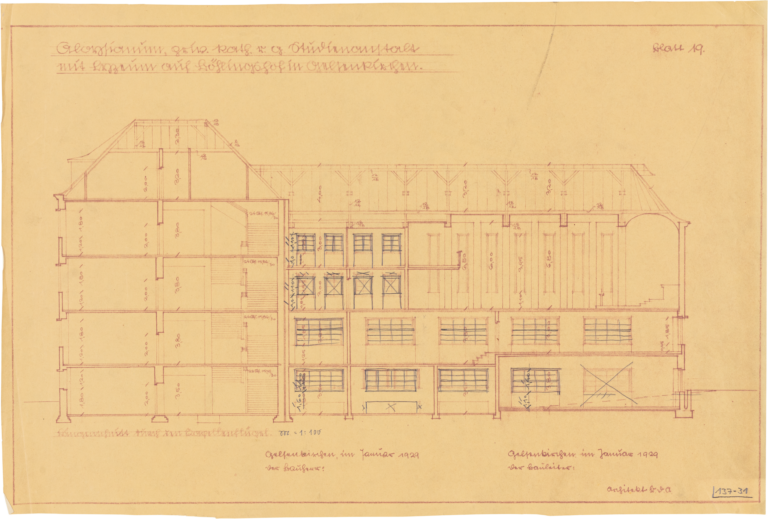

A longitudinal section through the chapel and the central building with the staircase shows the classical roof frame structure and two-storey design of the chapel. Of particular interest on this sheet are the slight corrections that trace the evolution of Franke’s design ideas. Whereas the last of the five basement windows is simply crossed out when viewed from the central building, the penultimate window is missing in the perspective drawing, thus visually demarcating the apse.

Despite their low height, the skyline of traditional hipped roofs defines the view of the school as seen from the spacious playground.

The architectural style of the Aloysianum

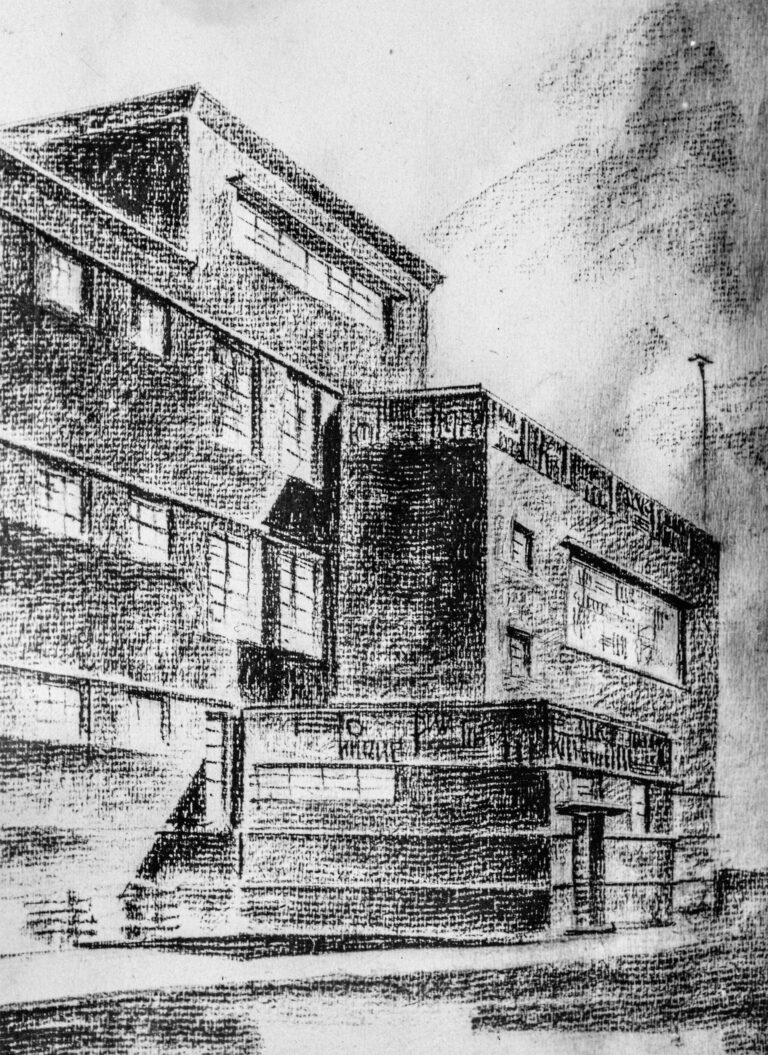

However, viewed from the narrow street space at the main entrance on Schultestrasse, it looks more like a modern flat-roofed building. This impression is also conveyed by the historical photographs and another perspective drawing by Franke from the archives. The perspective shows an alternative design of the entrance situation, which appears less imposing with a single-leaf door and small canopy. Here, too, the angle is chosen in such a way that the building ensemble resembles modern interlocking cubes.

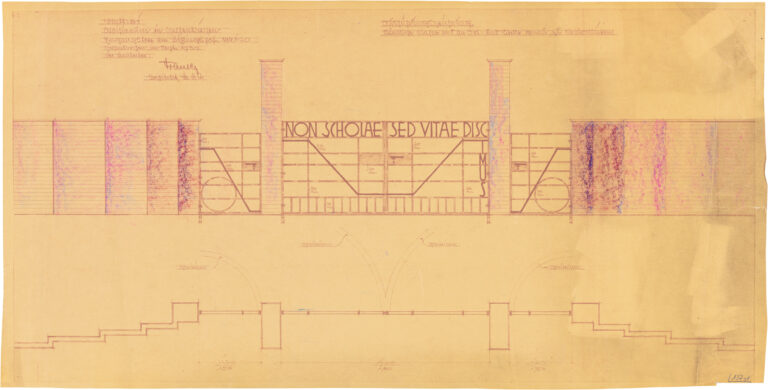

In addition to a delicate-looking flat roof as a visual continuation of the cornice, the actual main entrance is marked by its bricked roof columns, the wide, stringer-framed flight of steps and the Latin inscription – a greeting from the Franciscans – “pax et bonum” (“peace and well-being”). This is one of the few places where the geometric shapes of the bricks have been used for Expressionist design on the building. This building ornamentation was designed by Franke’s daughter Margarethe, 16 at the time. A gate to the playground was particularly elaborately designed, to which only the project plans in the Baukunstarchiv still testify. As can be seen on the plan, the brick wall of the playground recedes in increments towards the gate, creating a small forecourt. Two adjoining pedestrian iron gates are separated from the central gateway bearing the Seneca inscription “NON SCHOLAE SED VITAE DISCIMUS” (“We learn not for school, but for life”) by two distinctively tall supporting pillars. The symmetrical layout of the gateway with its geometric play of forms has been skilfully disrupted by the asymmetrical lettering.

Josef Franke is often labelled a modern traditionalist, a term that also applies to the Aloysianum building. Thepronounced horizontal structuring and staggering of the building units, together with the seemingly delicate flat roofs of the main entrance and the canopy on the playground side, and last but not least the elaborately designed school gate, derive from the formal canon of New Objectivity and also display typical elements of the Brick Expressionism widely adopted in the Rhenish-Westphalian industrial area. However, these contrast with the traditional hipped roofs of the complex. In a publication of his work edited by Franke in 1917, he states: “Purpose takes precedence over effect, content over form.”

The (building) history of the Aloysianum

Inaugurated in 1931, the Aloysianum had around 600 pupils in 18 classes despite the harsh economic situation during the Great Depression. In 1938, the Franciscan Sisters closed the school under pressure from the National Socialists. The city of Gelsenkirchen acquired the school building and opened the Kirdorf secondary school for girls, named after Emil Kirdorf, in 1939. During the Second World War, the building was mainly used as a military hospital until it was almost completely destroyed in November 1944. In March 1946, classes were resumed at the school, which was now a secondary school named after the author Ricarda Huch. Rebuilding the school took until 1955. Where the chapel once stood, a rectangular structure stands today, which also has a clinker brick façade and a hipped roof, but neither mullioned windows nor a continuous sandstone cornice. The assembly hall, which – as can be seen in the perspective drawing and in archived photos – had a single large-format, horizontal window, now has a row of large, upright windows formats following reconstruction. Intricately mullioned windows were also omitted from the science halls. Since the mid-1990s, this section has been adjoined by a new building that has little in common with Franke’s architectural language.

Conclusion

While Franke’s designs were initially still clearly rooted in Historicism, his buildings in the 1920s are mainly in the style of Brick Expressionism and later of New Objectivity. The importance of his work is reflected in the large number of his listed buildings, especially in his home town of Gelsenkirchen. These bear physical witness to the rapid urban development of the Ruhr region at the onset of the 20th century. Furthermore, Franke’s estate at the Baukunstarchiv NRW also documents the life and work of an architect in socially and politically unstable times.

The present text was first published in: Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, Wolfgang Sonne, Barbara Welzel (ed.): Bildung@Stadt_Bauten_Ruhr, Dortmund 2022, pp. 68–85.