Open-door centre

Sonja PizonkaThe publication “Jugendbauten unserer Zeit” on contemporary youth buildings came out in 1953. The editors presented recently built day care centres, children’s homes, boarding schools, youth hostels, youth homes and youth centres from Germany and abroad. The youth centres mentioned included buildings and designs by Otto Bartning, Jacob Berend Bakema, Alvar Aalto, Alfred Roth and Richard Neutra. These were regarded as examples of a potentially significant building task, as there had been only a few precedents in this area to date and it was thus still possible to develop new building forms in the design process.

In their own spaces

The editors also pointed out that youth centres had also come in for criticism: “Many think that it is not good to explicitly isolate young people in their own establishments […]. They justify their view by saying that the nuclear family is disintegrating anyway and should not be encouraged by providing separate places where children and parents can spend their free time”.

Proponents of youth centres, on the other hand, saw potential for young people to interact with their peers. To allow them to meet in their own spaces without membership of a group (including, for example, trade union youth groups, political parties, Christian denominations), there was the concept of the “open-door centre”. On this subject, the Gauting resolutions passed in 1953 stated: “The open-door centre is a leisure and meeting place in the independent pedagogic space and complements upbringing in the parental home, at school and at work. It serves all young people and must be open to all on a daily basis.” These resolutions were drafted by sub-committee members of the working group for youth care and youth welfare in Gauting, Upper Bavaria, serving as the definition of the term “open-door centre” and were to be the working basis for the ongoing development of the concept.

A “semi-open door” home

When the Jugendbund Neudeutschland opened its own youth centre in Dinslaken on 8 December 1958, it was initially to be a “semi-open door” home. This meant that there were areas on the premises for young people without membership as well as rooms reserved for the members of the youth association.

The Jugendbund Neudeutschland (ND) had been founded in 1919 as part of the Catholic youth movement. In Dinslaken, an ND group was formed in 1926. Banned under National Socialism, the groups re-established themselves in the post-war period; in Dinslaken around 80 members came together.

Their own youth centre

They initially met in rooms on the grounds of the former Pestalozzischule (school, now the Gartenschule), but these soon had to be vacated in the course of an extension of the school buildings. So they decided to build their own youth centre. The youth organised in the ND group were to decide on the activities in the house together with the adults who had previously belonged to the youth association and were now in the equivalent group for men. In retrospect, it was said: “We proceeded from the idea that the youth group should learn, going beyond its own interests, to reach out to non-organised youth, while the adults should leave behind their romanticised memories of youth and perform their own concrete tasks on behalf of today’s youth, as their free time permitted.”

“Tent” and “atrium”

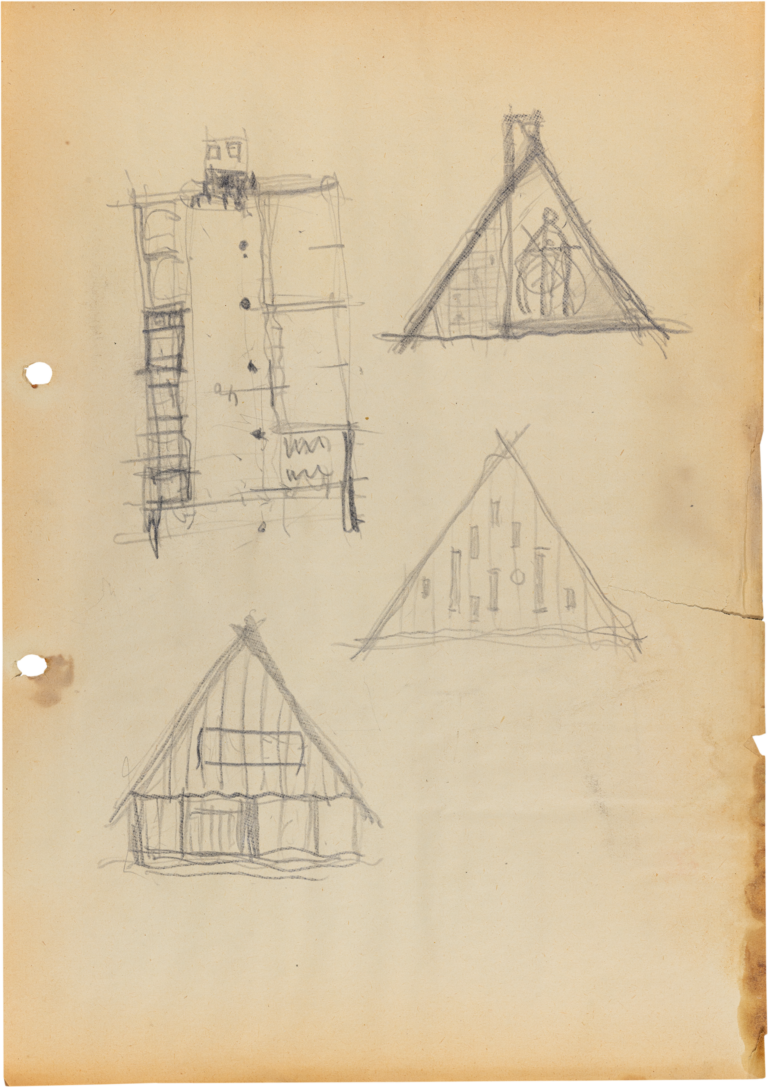

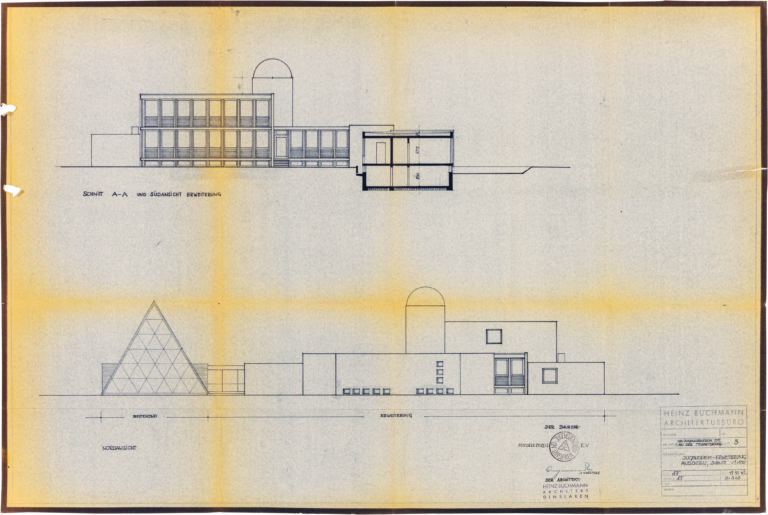

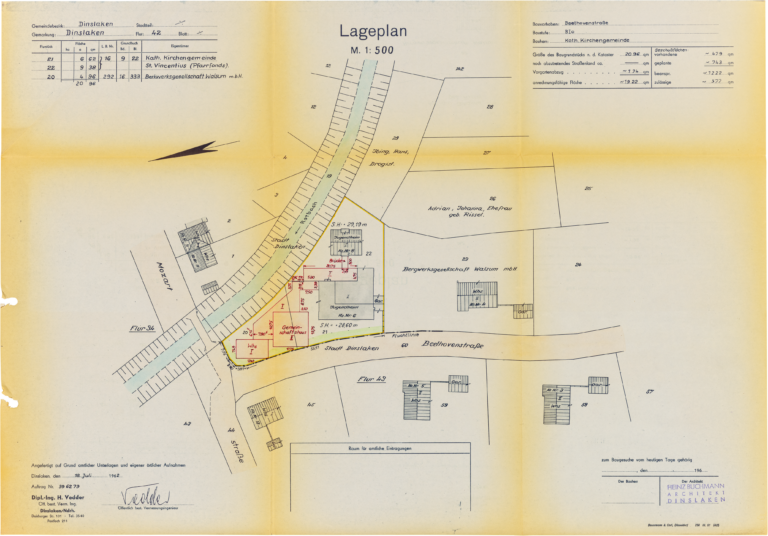

Starting in 1956, the architect Heinz Buchmann (1930–2004) from Dinslaken drew up the plans for the youth centre. He described the location of the property as follows: “The property is located in the west of Dinslaken in an area sparsely developed or yet to be occupied by well-appointed single-family houses. It adjoins a green belt that runs alongside the Rotbach stream and is only a short distance from the secondary school and the Burgtheater (approx. 350 m) via the Mozartbrücke (Mozart bridge) and Mozartstrasse. A sports ground is located on the Rotbach 500 metres downstream.” This meant the site was conveniently located in a housing estate close to the city centre, between the school and the sports ground. Buchmann devised a concept with two separate buildings. The so-called “tent”, a building under a gable roof that reached almost down the ground, was to be available for group work. The adjacent “atrium” bungalow was intended as an open-door building with workrooms, a library and discussion room.

A wide-open door

In Dinslaken it took only a few years for the original separation into group rooms and freely accessible areas to prove redundant. In 1968, Aloys Angenendt, initiator and first director of the ND Jugendzentrum (ND Youth Centre), recalled: “The ND Jugendzentrum became more and more a meeting place for the non-organised youth from the town and district. The number of young people visiting the centre grew rapidly from 200 to 400 and 600 to 800. The rooms that had been set aside for the organised youth now had to be made available for the varied wishes and needs of the non-organised. So the centre whose door had been semi-open became one with a wide-open door.” The ND group, which had met regularly in the tent, disbanded in 1966, but other organised groups continued to exist. Angenendt accounted for this as follows: “The willingness of young people to commit themselves firmly to a group as a community with shared lives and convictions grew weaker over the years, while there was a striking increase in the tendency to team up with peers for a limited time in the achievement a specific goal.”

Extension of the atrium

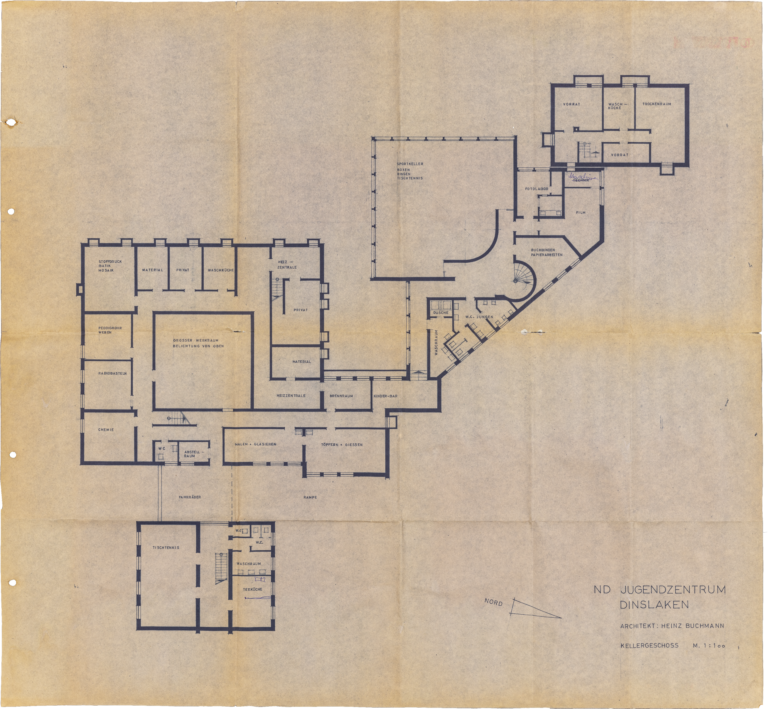

The youth centre became increasingly popular and those responsible were quite prepared to respond to the boys’ and girls’ wishes in the planned expansion. In the existing buildings, it was especially the common rooms for casual get-togethers and the workrooms in the atrium that attracted most interest. Therefore, Heinz Buchmann explained: “This led to the extension of the atrium and the addition of a group of buildings, whose liveliness responded to the young people’s searching restlessness and which comprised a bar, youth café, a hall as a meeting space as well as sports and communal rooms.” Buchmann continued his concept of an architecture with as many loosely connected areas as possible for different uses. He had planned a large recreation area on the ground floor and work and sports rooms in the basement. A ground plan of the basement, for example, shows areas for film, photography, bookbinding and papercraft as well as such sports as boxing, wrestling and table tennis.

Milk bar

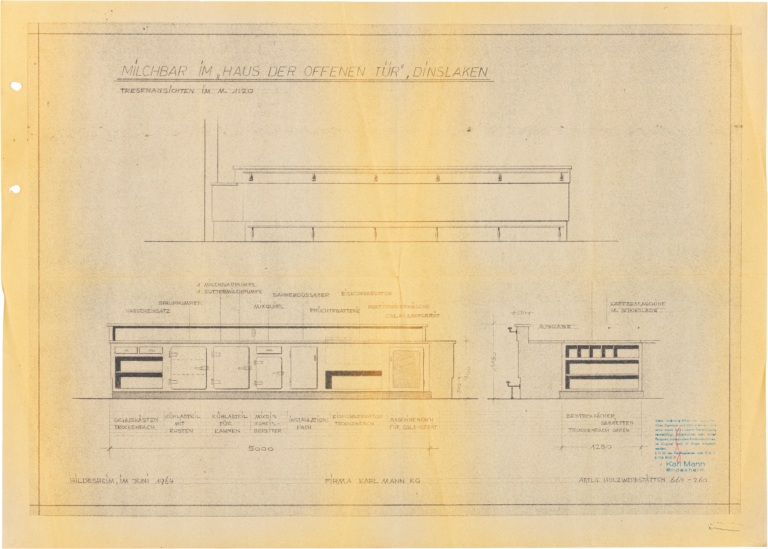

The architect also requested plans for a milk bar from the firm Karl Mann KG in Hildesheim, which built counters for serving the non-alcoholic drinks popular at the time. With the opening of the extension in 1965, there was not only more space for the young visitors, but amateur astronomers from Dinslaken and the surrounding area could now also use the newly inaugurated observatory, whose dome rose above the buildings of the youth centre. This extension meant that the Rotbach site was now almost fully occupied. Unlike many other facilities for boys and girls, the ND Jugendzentrum was a successful example of a new, purpose-built ensemble of buildings. The young people in Dinslaken were spared the experience of meeting in a makeshift facility. They had their own rooms at their disposal, which was also a token of appreciation and recognition. A study on youth centres stressed the importance of this factor: “One can hardly expect young people to feel at home in the long run in a ‘centre’ resembling a catacomb, a waiting room or a ramshackle shed.”

Visitors from Dinslaken, Walsum, Voerde and Hünxe

The “open-door centre” in Dinslaken was a success. In 1968, it was attended by an average of 432 young people per day, sometimes almost 700 on school-free days. The visitor statistics for that year showed the following figures: “Protestant 49.50%, Catholic 46.5%, other 4%. Of the visitors in 1968, 70% were boys and 30% girls. Visitors came from all over the district: 70% from Dinslaken, 21% from Walsum, 8% from Voerde and 1% from Hünxe. Over 50% of the boys and girls are children from families of workers and craftsmen.” The architecture with its multitude of rooms particularly accommodated the needs of the young visitors for gatherings and privacy; at the same time, it provided space for a varied programme of events. Highly popular in 1969, for example, were forum discussions on “Rebellious Youth” and “Youth Confronted with Alcohol and Drugs”. Small-scale dance parties, café afternoons and youth worship services were also popular.

Popular activities and new formats

Innovations announced for 1970 included tutoring in mathematics and German, English courses and a course in “experimental graphics”. Popular activities were maintained and new formats were added again and again. Heinz Buchmann, who was also a member of the association of friends, retained close ties with the ND Jugendzentrum for many years and supervised various restoration and modernisation measures. In Dinslaken and the surrounding area, he designed other buildings, including school buildings, hostels and swimming pools. Buchmann also designed the churches Heilig Geist (1963) and Heilig Blut (1965) in Dinslaken (#Church of the Holy Blood) and, in collaboration with the sculptor Josef Rikus, the church dedicated to Pope John XIII (1969) in Cologne.

The present text was first published in: Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, Wolfgang Sonne, Barbara Welzel (ed.): Bildung@Stadt_Bauten_Ruhr, Dortmund 2022, pp. 86–99.