Richness of the spatial experience

Christin Ruppio“And yet the spiritual and intellectual centre of the parish should also be visibly distinguished in the midst of its remodelling, through plain meaningfulness and contemplativeness.” Heinz Buchmann

The introductory quotation comes from the explanatory report attached by the architect Heinz Buchmann to his competition entry for the construction of the now no longer extant Kirche Heilig Blut (Church of the Holy Blood) in Dinslaken. Buchmann had already realised the Heilig-Geist-Kirche (Church of the Holy Spirit, 1961) in the Dinslaken district of Hiesfeld for the same parish and also won the competition for Heilig Blut (1965) in the Bruch district with his diversified room layout. In the explanatory report, Buchmann outlines the basic ideas for his design of a church that – in the sense of a community centre – fits into a growing part of the town and plays its part, but is also to stand out as a special place within this setting. Connected by a main traffic artery and bordering Dinslaken’s town centre to the north, the Bruch district developed rapidly in the period after the Second World War. As the Catholic congregation was growing steadily, the district’s planning for a church of its own began as early as 1953, but did not come to fruition until 1965.

Bell tower

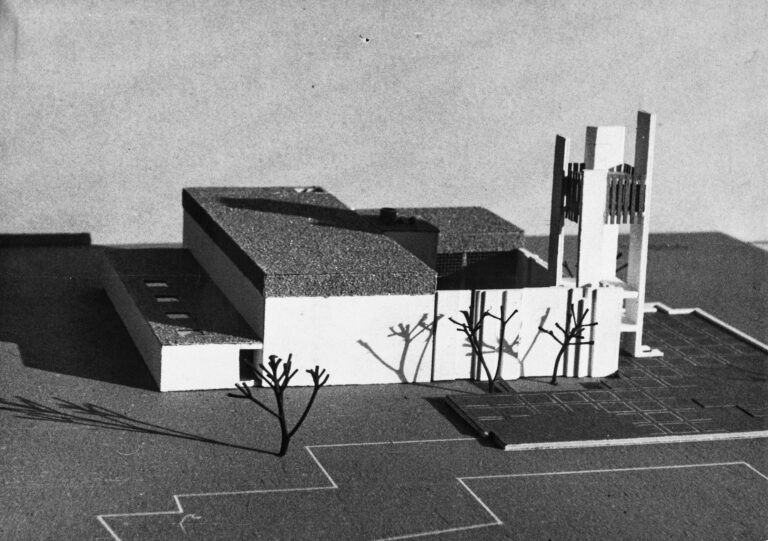

“The extreme simplicity in the choice of materials should match the richness of the spatial experience […]”, Buchmann states in his explanatory report, drawing attention here to two key features of the building. The façades of the church were made of a mix of brick and concrete, with brick dominating the exterior view from the street, since the bell tower and the surrounding wall consisted largely of this material. Through the use of flat roofs, the elevated nave and the transept adjoining it to the south hardly seem to have stood out from the surroundings when viewed from the street. Only the bell tower, which as part of the surrounding wall at the south-western corner of the site marked the entrance to the courtyard, made the church visible from afar. Buchmann decided against a solid tower, however, by arranging four free-standing walls with wide passages between them and connecting them only with the belfry in the upper quarter. Buchmann had already tested the idea of a less monumental tower with lattice elements made of reinforced concrete a few years earlier when building the Heilig-Geist-Kirche and further developed this look for Heilig Blut.

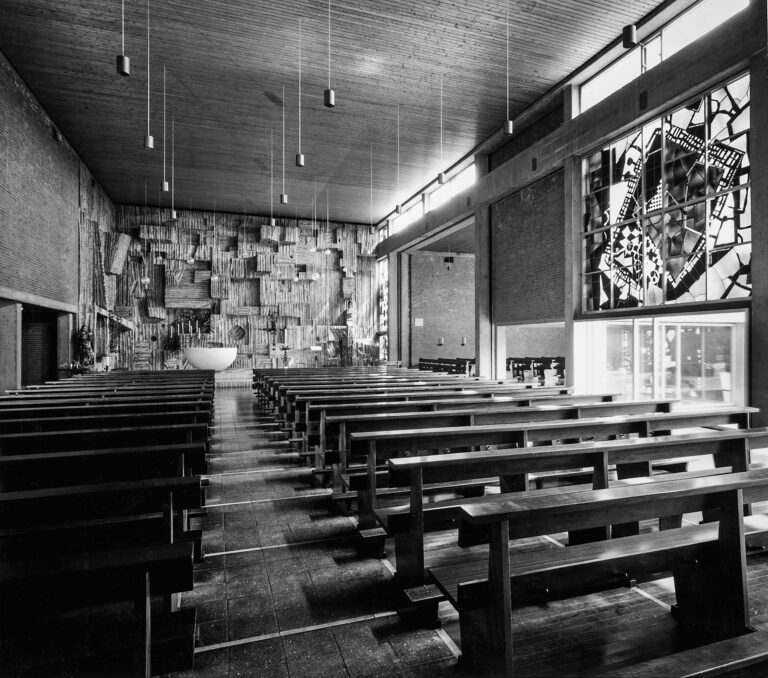

Distinctive altar wall

In the interior, on the other hand, the church exhibits design features that Buchmann was not to fully exploit until a few years later with the construction of St. Johannes XXIII (St John XXIII, 1969) in Cologne. Together with the sculptor Josef Rikus, Buchmann developed a spatial sculpture made of concrete in Cologne, which is now a listed building. But in Dinslaken, Buchmann also cooperated with an artist – Waldemar Kuhn – to introduce concrete as a sculptural design element and to realise a distinctive altar wall. Kuhn pointed out that the wall was “not designed on a drawing board with protractor and ruler, but measured with the human cubit and foot”, in other words, a spatial sculpture on the human scale.

Gradations

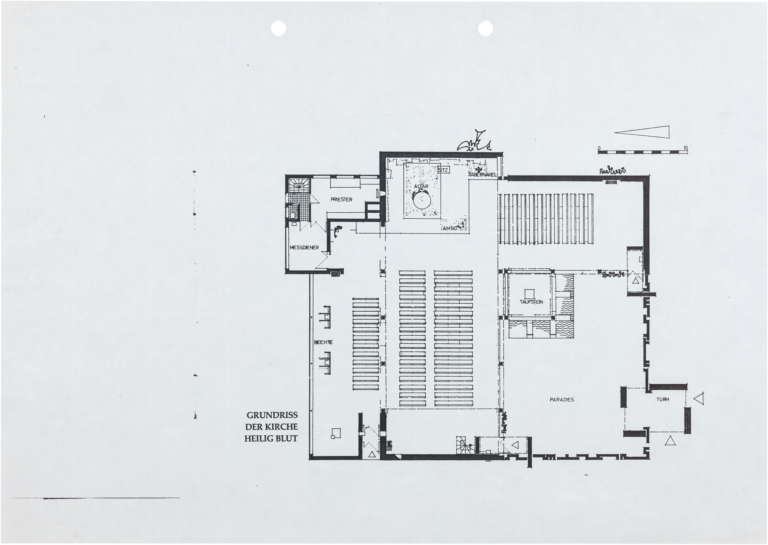

If one compares photographs showing the surrounding wall with the competition model, it becomes clear that the actually built wall was much lower. On the model, it extends to the eaves of the roof; in the final form, it was just high enough to obstruct the gaze of passers-by into the courtyard. About the courtyard Buchmann writes: “The ‘Paradise’ we want to enter via the tower is already part of the House of God, surrounded by a wall that encloses a large quadrangle, which is to be divided by a glass curtain into outer and inner precincts.” The interior and exterior of the church exhibited gradations. Seen from the street, the tower and walls shielded the Paradise – i.e. the courtyard – and yet permitted an initial glimpse of the flat-roofed buildings with their elaborately designed windows.

The Idea of an earthly Garden of Eden

On the western edge of the courtyard, a door invited the visitor to enter the inner sanctum; on the eastern edge, the baptistery, set in the right angle between the nave and the transept, allowed a first glimpse inside. In the courtyard, the sacramental significance of elemental water found expression in a basin surrounding the chapel. The inclusion of plants and water was a further referenced to the idea of an earthly Garden of Eden. In the Christian faith, paradise is not only a place lost through sin, but also a future place – at the end of time – and one whose location in one’s own present has been sought for centuries. These multiple readings of the term “paradise” impart special significance to its inclusion as an architectural element in this innovative sacred building. At the same time, the courtyard serves as a practical transitional zone between the urban space right on a main road and a place of contemplation. Buchmann concludes his description of the architectural dovetailing of the inner and outer precincts as follows: “A large space oriented to the altar […].” Buchmann also achieved this effect of a subdivided but coherent space by providing the nave’s lower window zone with window glass rather than stained glass – a direct line of sight was possible (#Lamellar Model Church). The low enclosure and the open design of the bell tower continued this gradated opening into the public space surrounding the church.

Sculpturally designed east wall

In the architect’s estate there is an extract from a brochure published for the consecration of the church, in which the priest of the St Vincent parish discusses the meaning of “Holy Blood”. He writes: “Water and blood refer to the two basic sacraments, baptism and the Eucharist. […] The Heilig-Blut-Kirche therefore gives the altar and the baptismal fountain prominent positions.” Buchmann noted this layout of the space in his explanatory report: “The core of the space is the heavy, dark altar in front of the brightly lit, sculptural east wall. It is brought forward almost to the point where the axes of the room intersect and is raised only slightly above the ground floor level. All the elements of the room are set in relation to the altar. This layout is evident from the floor plan as well as from a photograph showing the view from the entrance area to the altar wall. The sculpturally designed east wall together with the low ceiling height and the reiteration of the central walkway by the ceiling lighting draw those entering towards the altar. The transept adjoining the altar area to the south was also furnished with rows of pews facing the altar.

Bright daylight

On the eastern wall of this space were the Stations of the Cross on twelve stone relief panels by the artist Joseph Krautwald. Since the transept was set somewhat lower than the nave, bright daylight entered the altar area through a window zone that was also glazed with transparent glass. The central zones of the glazing on the south façade of the nave as well as the entire window in the south-east corner of the chancel were fitted with stained glass windows by Joachim Klos, which are now preserved by the Stiftung Forschungsstelle Glasmalerei des 20. Jahrhunderts, an organisation devoted to preserving 20th-century stained glass artwork. In addition to this clear orientation towards the main altar, Buchmann also created spaces for personal worship and contemplation. Buchmann accommodated the side altar required in the competition documents as well as a place for confession in the lower northern aisle.

Crèche

The Heilig-Blut-Kirche was demolished in 2009, on the grounds of financial constraints. A crèche was built on the same site, with bricks from the demolished church built into its walls. The parish continues to celebrate Holy Mass twice a week in the adjoining community centre. Although the building could not be preserved, its interior lives on in partner parishes in Romania and Africa. Ten years after demolition, the community centre was given a new bell tower, based on Heinz Buchmann’s design, albeit of much smaller scale.

The present text was first published in: Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, Wolfgang Sonne, Barbara Welzel (ed.): Religion@Stadt_Bauten_Ruhr, Dortmund 2021, pp. 214–225.