Library for all

Judith Klein, Christin RuppioThe founding of the Ruhr University of Bochum in 1961 can be understood as an important step in remedying the “educational emergency” feared at the time. It therefore not only makes sense for navigation on campus that the library is located on the Magistrale – i.e. the main traffic artery – but this placement can also be interpreted programmatically. The Ruhr University of Bochum has always been a university “for all”, intended to also enable members of less affluent or non-academic families to study at university.

System of prefabricated elements

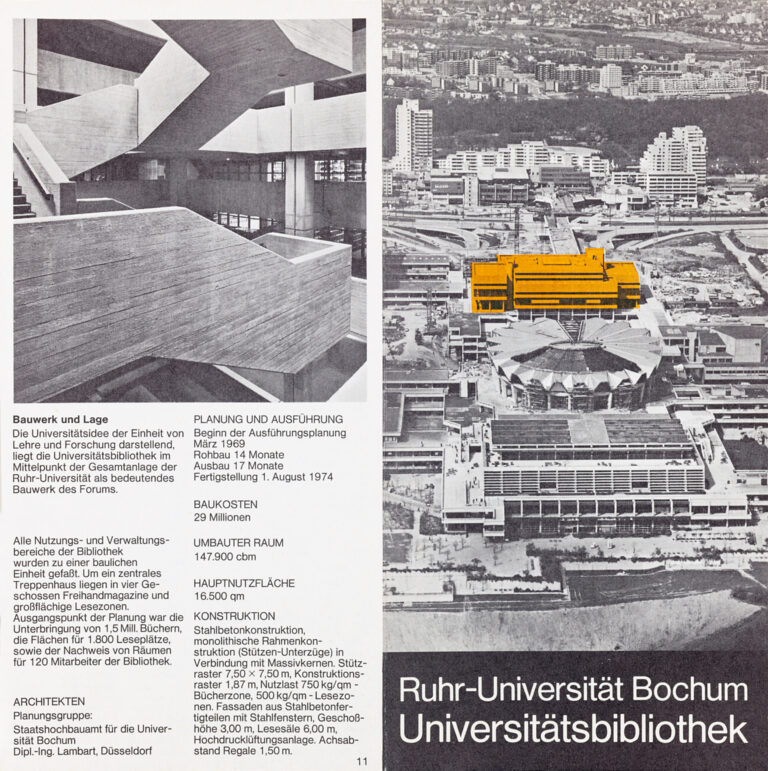

An open-stack library, which forms the hub in the ensemble with the sculpturally prominent Auditorium Maximum (main lecture theatre) and a spacious square extending between the two buildings, expresses this conception of an open university. Around this ensemble, the paths run on levels at different heights, offering varied views of the heart of the campus. The cover of an information booklet found in the estate of the responsible architect Bruno Lambart highlights this positioning of the University Library with a coloured marker.

The library built from 1970 to 1974 is a reinforced concrete structure devoid of load-bearing walls and supported by columns that are partly visible on the outside as well. Like the other buildings on the campus designed by Hentrich, Petschnigg & Partner, the library was built using a system of prefabricated elements, which was specially developed for this project and is based on a module of 7.50 metres. This building features both mass-produced precast concrete elements and concrete poured in situ. For the production of the precast concrete elements, a temporary production facility was run on site.

Zones and open spaces

The look of the exterior façades is dictated by four materials: steel, concrete, brick and glass. The different types of concrete finish – textured, smooth and off-form – enliven the façades in a special way (#Church St Nicolai). There are no plastered or ornamental elements. The library is thus a good example of the “material honesty” of post-war modernism.

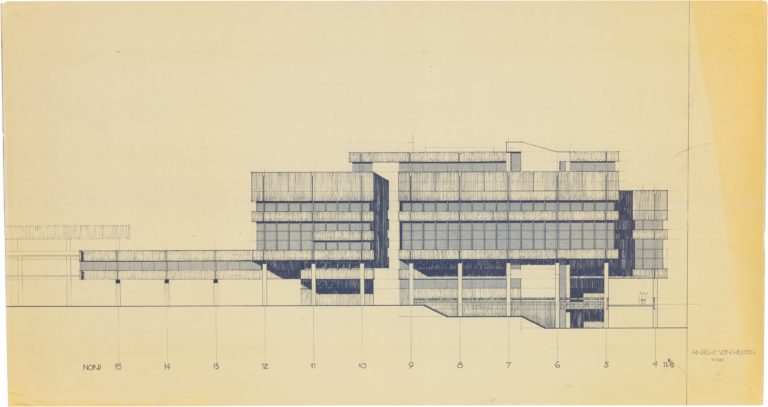

As a view from the west clearly shows, the building is divided into three superimposed zones. The upper third looks particularly compact and consists essentially of textured concrete slabs; in the middle third, glass windows with red steel frames – partly punctuated by concrete elements – begin to open up the façade; finally, in the lower third, the building recedes to reveal load-bearing columns. This opening of the façade in the lower third creates walkways and open spaces that connect the south façade of the library and the square in front of it on this side. It is here where the rooms of the university’s art collection are located today that a cafeteria and the main entrance were originally planned.

Places of gathering and interaction

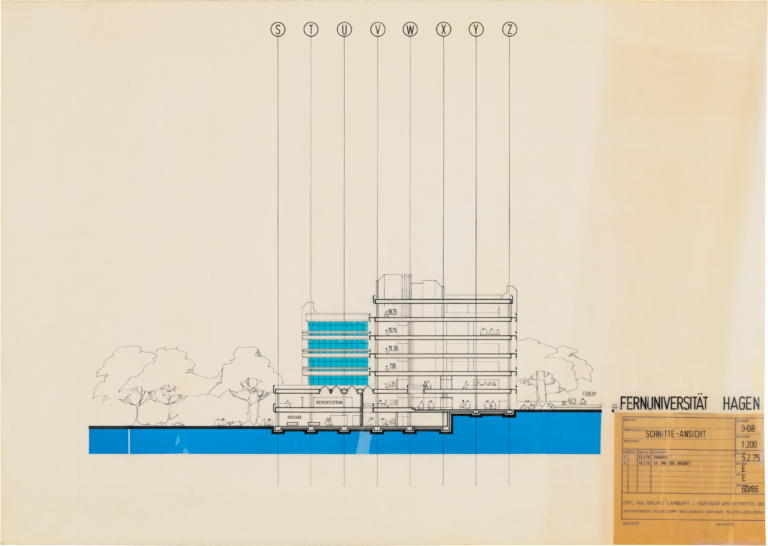

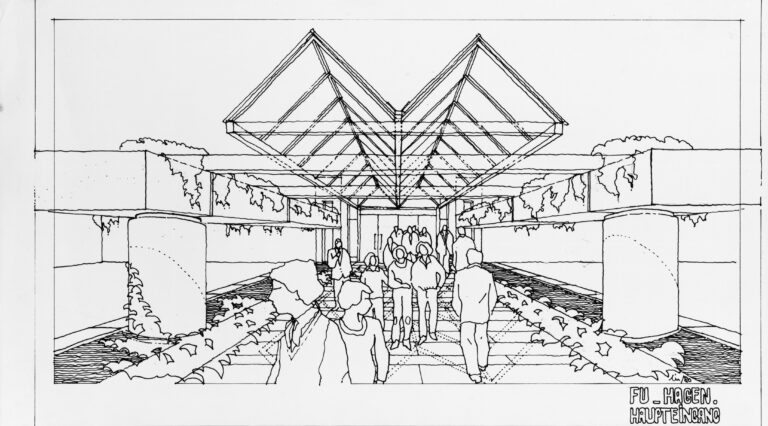

The decision to integrate the art collection into the library building meant having to move the main entrance to the north façade. Although the inclusion of the art collection is an enrichment of the central ensemble on the Magistrale, for Lambart’s design it also meant moving the library away somewhat from the central forum. In many of the designs in the architect’s estate, there is evidence that he considered forums important as places of gathering and interaction, especially for educational buildings, both indoors and outdoors. One example is the collection on the administration building of the University of Hagen, which Lambart built between 1977 and 1979. As this was the first – and still the only state-run – distance-learning university in the Federal Republic, a completely new spatial plan had to be developed here. A section shows how Lambart also planned the area outside the system building as a forum and used human figures in the plan to incorporate the ambient quality of the various building areas. A perspective view from the collection on the distance-learning university illustrates how Lambart imagined the lively location.

Central staircase

And Lambart also enlivened the interior of the Ruhr University Library by creating a variety of meeting and working zones as well as making skilful use of materials. The physical aesthetics of the off-form concrete, which was also used on the building’s exterior, is continued inside the library. On the unsupported and sculptural concrete staircase – the central access element – in particular, the material seems to be literally showcased by the natural daylight streaming in from above. The interplay of light and shade draws particular attention to the underside view and thus to the engineering achievement of constructing the staircase as a free-standing structure. Around the central staircase, there are galleries on each floor that serve as places for communication, for short breaks, but also as workplaces. The open-stack book collections are separated from the gallery by glass walls. In this area, further reading and work places are located directly at the strip windows. This makes optimal use of natural daylight, and at the same time the book collection is protected from excessive direct sunlight.

Third Place

This “library for all” is a place of learning and an information centre, but with the break areas in the galleries it is also an important Third Place for students and researchers. To help them navigate within the building, Lambart designed from the outset a numerically and colour-coded wayfinding system for the library. The coloured number combinations are applied straight onto the exposed concrete and refer to the various areas.

Open-stack principle

During the long period between the opening of the Ruhr University of Bochum in 1965 and the commissioning of the library in 1974, the library system at many universities was changed from closed to open stacks. The earlier system required large stacks from which books were only issued on request. The Ruhr University of Bochum was one of the first universities to design its library on the open-stack principle; in other words, the books are located in freely accessible rooms that allow anyone interested to take a book from the shelf. The realisation of this new, pioneering system was only possible through the use of new revolutionary computer technology from Siemens. And the architecture also had to be completely rethought.

Art collection

Today, two works of art outside the library show that it is a place that evolves with the campus and the demands of teaching and research (#TU Dortmund, EF 50). In the search for a suitable memorial against the War in Yugoslavia, it was decided at the end of the 1990s to bring Picasso’s “Guernica” – which had previously been reproduced elsewhere on campus as an anti-war memorial but had been destroyed during repairs – back to the Bochum campus. Since Picasso’s heirs banned a painted copy, a photographic reproduction has since adorned part of the south façade. Since 2005, there have also been two neon installations by the artist Mischa Kuball on the library’s north and south façades. On the south façade, the individual letters of “Kunstsammlung der Ruhr University of Bochum” (art collection of the Ruhr University of Bochum) flash at irregular intervals. On the north side, a mirror image of “Universitätsbibliothek Bochum” (University Library Bochum) is affixed, thus referring to the original plan to place the main entrance to the south, towards the Forum and the Auditorium Maximum.

Audio Guide

And the building has also been the focus of research and public interest in recent times: in 2018, it was commended by the Big Beautiful Buildings initiative. In 2020, the audio guide “ZukunftsSPUREN” (Traces of the Future) was developed in cooperation with the project “Stadt Bauten Ruhr”, in which Bruno Lambart’s library is discussed as a region-defining building. The guide can also be interpreted as an invitation to residents of the region and interested parties to truly discover this place as a “library for all”.

The present text was first published in: Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, Wolfgang Sonne, Barbara Welzel (ed.): Bildung@Stadt_Bauten_Ruhr, Dortmund 2022, pp. 294–307.