An urban structure of Jewish culture

Christos StremmenosWith the words “Who sings of love a house shall build, who cannot love stays unfulfilled” the Shulamite summed up the women’s conditions for the building of the new temple. The two verses borrowed from the festive play “Salomo” were spoken at the inauguration of the new synagogue in Essen on 25.9.1913 in the new community hall designed for 1,400 people. Appearing before Solomon in the play are not only Solomon’s lover, the Shulamite, accompanied by the women, but also the elders, the artist Hiram, the children, the boy who has returned to his true mother through the king’s wise judgement, and the king’s mother to emphatically express their will to build the temple by contributing their respective points of view.

The play written by Rabbi Emil Bernhard Cohn in celebration of the dedication of the new synagogue tells the story of Solomon, who reports his vision to his people “to create more beautiful things than we have created” in order to make “the diadem of the earth, the glorious lofty City of Jerusalem! … loftier still” with a temple building to crown it. After initial misunderstandings and their resolution by consulting with the representatives of his people, the king was persuaded that the building of the temple could only be mastered with the involvement and efforts of all, as a collective, professed work of love for God, for the community and for Jerusalem, which, with the building that he intended, was to become even grander and loftier.

The joyful festival play can be interpreted as an allegorical reflection on the “most splendid” synagogue building, as praised by commentators immediately after the two years it took to build. Through the voices of the Old Testament figures, the author announced that this building also represented such a profession and labour of love: to God, to the congregation, to German society and also to the city of Essen, which this magnificent building has ennobled more than most. With a votive plaque attached to the entrance’s arched reveal, a pledge of allegiance to the Kaiser and the empire was also visibly integrated into the building.

An appropriate location

With the growth of the Jewish community in the course of the industrialisation of the Ruhr from about 600 in c.1870 to about 3700 members in 1913, the synagogue building located in Webergasse (today Gerswidastrasse) on the north-eastern fringe of Essen’s Old Town became too small as a place of assembly. The pressure grew for an alternative location or even a new synagogue building, and suitable solutions were sought. With the acquisition of a plot of land at the junction of Alfredistrasse and Steeler Strasse in 1905 and the holding of a nationwide architecture competition in 1907, big steps were taken in the new synagogue project. The choice of site is not only justified by the proximity of the Jewish population, 80 per cent of whom lived in the adjoining Old Town. For the special triangular shape of the site, giving the synagogue a privileged location, offered the rapidly growing and increasingly confident “liberally minded unified congregation” an appropriate place for the erection of a new, prestigious synagogue building. With a difference in levels of five metres from the lowest point at the intersection of the two streets at Schützenbahn to the highest point on the eastern boundary of the site in Steeler Strasse, the site had a special sloping position with an exposed orientation towards the Old Town and was predestined to create a concise, tapering counterpart.

A Synagogue of metropolitan Aura

Edmund Körner’s synagogue design affirms the special location and topography and makes use of the characteristics of the slope and shape of the plot. Along a central west-east axis drawn from the narrowest to the widest point, he creates a choreography of successive alternating urban and synagogue spaces. The various main volumes, such as the bordered forecourt, the concave gabled house, the central dome structure, and the domed-roof turrets rising at the corners, are also interwoven via this axis to form a massive, upwardly staggered cubature. A varied, increasingly widening and rising sequence of spaces is composed with a cloistered forecourt leading to steps rising from street level, an arched entrance, an adjoining porch and the central domed hall with a semi-circular gallery, reaching a spatial climax at the highest point under the large dome in front of the monumentally articulated Torah shrine. But Körner’s interweaving of the synagogue building with the urban texture extended much further before the Second World War and began not at the kerb outside the synagogue along Schützenbahn. Framed by historic Old Town houses, a visual axis meandered from Marktplatz along Steeler Strasse (now built-over), showcasing the massive synagogue building forming the entrance to the street. Consequently, the heart of the city, the central historic Marktplatz (marketplace) and the large domed-roof hall with the monumental Torah shrine were spatially interconnected via this axis. Placing it in its urban context, most commentators refer to it as a free-standing synagogue building. However, this only partially reflects the quality of integration. With the directly adjoining community centre and secondary school along Steeler Strasse and the planned addition of a casino on Alfredistrasse, the building looks more like a distinct cornerstone crowning the urban fabric in stone.

Körner’s working method had the artistic aspiration of a holistic view of architecture, beginning with the building’s insertion in the stone urban fabric and extending to the formulation of original details as well as the design of furnishings under the roof of architecture of monumental proportions. With Jewish-Oriental and Christian-Occidental typological and ornamental borrowings and the use of new building materials and production methods, he succeeded in creating an exciting atmospheric combination of modernity and tradition, and produced a striking synagogue building with a noble metropolitan face. His design was one of three prize-winners from 72 entries in the architectural competition held in 1907. In 1908, he was commissioned with the planning and construction of the synagogue subject to the condition that he revise his submitted and squat-looking competition design in consultation with the congregation. In connection with this commission, he was even appointed artistic director of the design department of the Essen building authority in 1909, a circumstance testifying to the importance that Essen’s civic leaders attached to this building.

With the active participation of Rabbi Dr Salomon Samuel, Körner revised his original design and created a “Gesamtkunstwerk”, a work embracing all the arts. By using reinforced concrete and steel for the construction of the load-bearing elements, regional shell-bearing limestone worked into block form for the cladding of the outer walls, and by adopting traditional Jewish symbolism and ornamentation in a contemporary interpretation, Körner created a fusion of the traditional and the modern and generated his own expressive monumentality.

Malicious Destruction

However, the Jewish community was only able to use its unique new synagogue building, which dominated Essen’s skyline and was known and highly acclaimed well outside the Ruhr region, for 25 years. During the violent incidents of the November pogroms from 9 to 10 November 1938, the Essen synagogue building was also set on fire, along with numerous synagogues and Jewish institutions throughout Germany. The building suffered severe damage to its interior, and the Jewish community lost its impressive place of assembly. After defamation, persecution, genocide, and material and cultural dispossession during the Nazi era, the once large Jewish community, which had swollen to 4,500 members, numbered only a few survivors. Despite heavy bombing raids, the synagogue building at Steeler Tor was one of the few buildings in the immediate vicinity of the city centre whose outer shell survived the Second World War virtually intact and, with its remaining solid envelope, acted as a memorial in stone to pogrom, expulsion, persecution and genocide.

Negation of a memorial

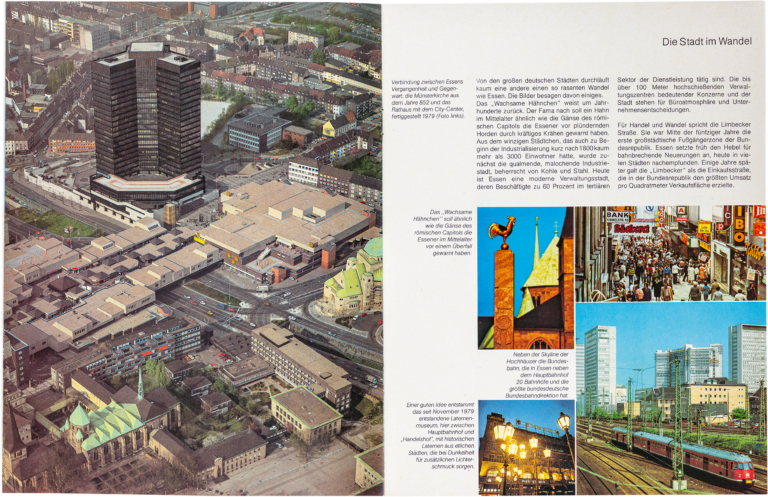

Despite the exposed position and presence of the building in the urban space, decades were to pass before the location’s relevance to history manifested appropriately in the collective memory. Much of what was not damaged or destroyed by war and the Nazi dictatorship was often lost in the course of car-friendly urban redevelopment. The forecourt, which in Körner’s design was compositionally and choreographically significant and mediated between the synagogue and the city, was completely demolished to make space for cars in Schützenbahn in front of it, despite the fact that it had survived the war almost unscathed. The building thus found itself right alongside an expressway planned and designed solely to aid the flow of motorised traffic. Reconstruction – which to a large extent also initiated the remodelling of the city – also transformed the immediate surroundings of the city centre into an almost interchangeable modern urban landscape. In a booklet published by the city marketing department in 1981, Essen presented itself as a city that had transformed itself from a “smoky industrial city “ into a successful and modern administrative and commercial metropolis, 60 per cent of whose population was now employed in the tertiary sector. The introductory aerial photograph very impressively shows the effects of this radical rebuilding. The expansion of the city centre was carried out solely in accordance with commercial, administrative and traffic needs. Today’s skyline is clearly dominated by the new town hall, built in 1979 on a plot of land outside the historic Old Town, and a bridge structure designed as a shopping arcade over Schützenbahn, planned to ensure a pedestrian link from the new town hall to the city centre. The synagogue with Essen Cathedral and the cathedral treasury opposite are the only landmarks referring to the location as it once was and fragmentarily highlighting the former historic urban fabric.

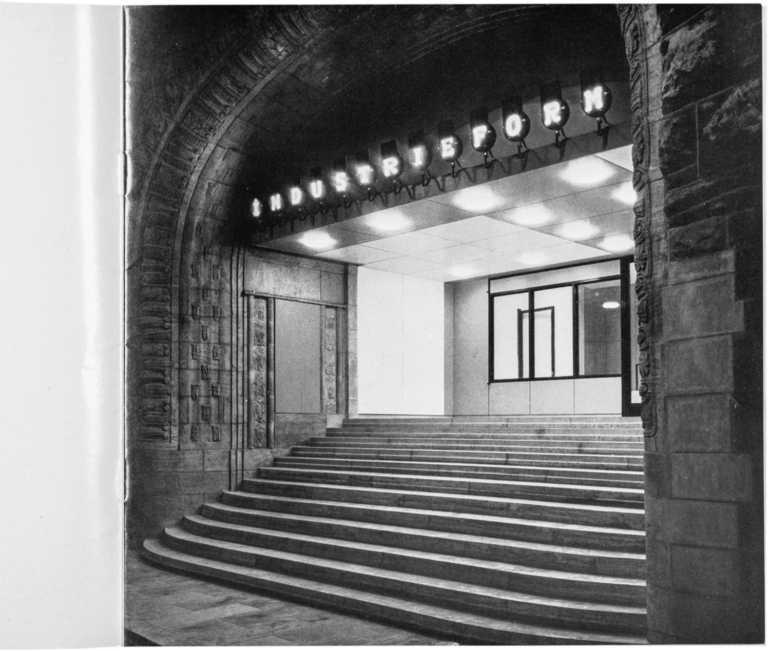

However, the destruction that the fabric of the old synagogue building suffered in the post-war period weighs far more heavily. In 1959, the city of Essen purchased the site of the former synagogue and in 1961 made the rooms available as an exhibition space for the “Industrieform” collection, which had moved out of the small building of Villa Hügel. With the presentation of beautifully designed objects and utilitarian items from industrial production in permanent and temporary exhibitions, the young institution had dedicated itself to promoting good function-conscious form and design. With newly inserted galleries, mezzanines and a free-standing staircase, an exhibition architecture was implanted whose underlying design intention was certainly discernible, but at the same time made no attempt to enter into dialogue with the existing synagogue space and its historical contours. Thus, remarkably, a reconstruction of the interior took place at the expense of the still extant structural fabric, which had survived arson and war and was stripped back to a white shell. The booklets published in the first few years of the “Industrieform” museum make no mention whatsoever of the site or of the old synagogue building and offer a view of an exhibition space in which the architectural shell has stepped back in favour of a presentation that is as free of distractions as possible. The reduction of the context to a white, self-effacing cube may be justified for museum spaces and concerns; in this specific case, however, it seems more like a negation of the site, disregarding its history.

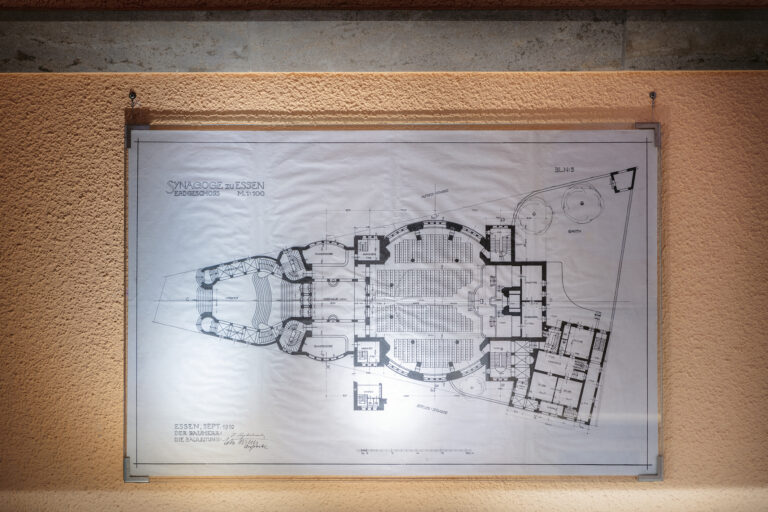

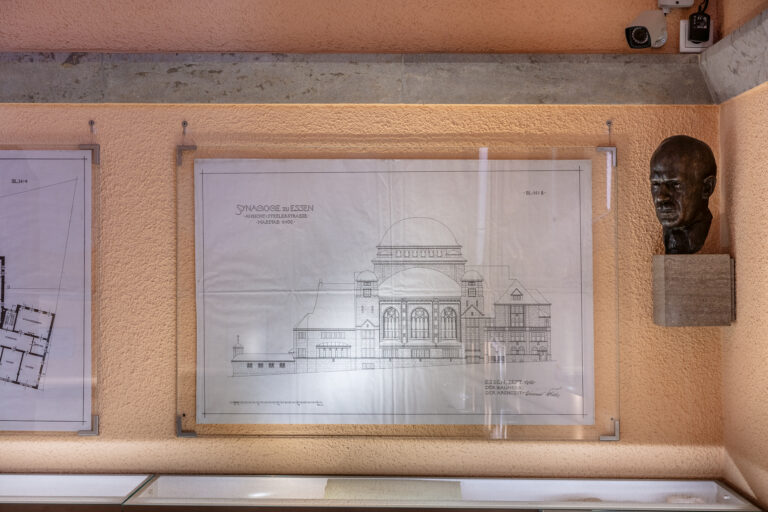

Rediscovery of an urban structure of Jewish culture

The “rediscovery” of the location and its inherited solid materiality only began in stages. In 1979, a short circuit caused a fire that destroyed a large part of the exhibition. When the “Industrieform” museum moved out in 1979, Essen’s city council decided, after lengthy discussions in the same year, to establish the Essen Old Synagogue memorial. During reconstruction work from 1988 to 1986, the synagogue was returned to its original appearance in a plain yet highly atmospheric manner. After several years of debate about the purpose and detailing of the programme as a place of remembrance, memorial, exhibition and event venue, the Haus Jüdischer Kultur (House of Jewish Culture) has now been housed in the former synagogue building since 2010. The house’s permanent exhibition includes the sections Sources of Jewish Tradition, Holidays and Shabbat, Jewish Way of Life, History of Essen’s Jews and History of the House; the latter also contains original drawings from 1910 of the revised synagogue design penned by Edmund Körner. The Haus Jüdischer Kultur accommodated by the historic building is an institution that does not focus solely on the brutalities and cruelties of persecution and killing, but presents Jewish life in all its traditional and modern facets as a thriving culture. Jewish culture thus again finds expression in a building that is one of the most striking and magnificent urban structures in the Ruhr region and Germany.

Rediscovery of an urban structure of Jewish culture

The “rediscovery” of the location and its inherited solid materiality only began in stages. In 1979, a short circuit caused a fire that destroyed a large part of the exhibition. When the “Industrieform” museum moved out in 1979, Essen’s city council decided, after lengthy discussions in the same year, to establish the Essen Old Synagogue memorial. During reconstruction work from 1988 to 1986, the synagogue was returned to its original appearance in a plain yet highly atmospheric manner. After several years of debate about the purpose and detailing of the programme as a place of remembrance, memorial, exhibition and event venue, the Haus Jüdischer Kultur (House of Jewish Culture) has now been housed in the former synagogue building since 2010. The house’s permanent exhibition includes the sections Sources of Jewish Tradition, Holidays and Shabbat, Jewish Way of Life, History of Essen’s Jews and History of the House; the latter also contains original drawings from 1910 of the revised synagogue design penned by Edmund Körner.9 The Haus Jüdischer Kultur accommodated by the historic building is an institution that does not focus solely on the brutalities and cruelties of persecution and killing, but presents Jewish life in all its traditional and modern facets as a thriving culture. Jewish culture thus again finds expression in a building that is one of the most striking and magnificent urban structures in the Ruhr region and Germany.

The present text was first published in: Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, Wolfgang Sonne, Barbara Welzel (ed.): Religion@Stadt_Bauten_Ruhr, Dortmund 2021, pp. 90–105.