Urban feature in the campus landscape

Wolfgang SonneA shop window facing the street, a façade overlooking public space, a building that flies the flag: to explain the radical nature of Christoph Mäckler’s IBZ, the Internationales Begegnungszentrum (International Meeting Centre) of TU Dortmund University, you have to dig very deep. Our universities today are an achievement of the European Middle Ages or, more precisely, of the medieval towns and their urban societies. After centuries of monastic exile – often programmatically secluded in the solitude of the countryside – knowledge returned bit by bit from the 12th century onwards to the centre of life in the nascent cities where it had once been at home in antiquity. The university buildings of Bologna, Paris or Oxford have always been located in the middle of the urban setting, giving their neighbourhoods their own character. These close ties between town and university remained the predominant model throughout Europe for a long time and led to the phenomenon of university towns with their university buildings integrated into the urban fabric.

Campus universities

As a counter-model, the idea of the campus university emerged in America in the 18th century, paradigmatically realised in Thomas Jefferson’s University of Virginia: a university campus of its own, secluded from the hustle and bustle and the dangers of the town, located in a rural setting and therefore called “campus”, i.e. “field”; a return of the monastic model in the Age of Enlightenment. In the USA, without an urban cultural tradition of its own, this model quickly became widespread. In Europe, on the other hand, it didn’t emerge until the 20th century, because universities existed in an urban context.

Detached from the city

It was only in the context of functionalist urban planning with its ideal of separated uses that the campus idea also fell on fertile soil in Europe. The National Socialists dreamt of a monofunctional university city in the west of Berlin – removed from the diverse and potentially unsettling and uncontrollable life of the big city. With the advent of the car-friendly town of the 1960s, campus universities located away from the towns and cities and served by motorways became a reality: Bochum (#Ruhr University of Bochum, Competition design) and Bielefeld are the most distinctive university machines built on green fields, untouched by the challenges of urban impositions – and Dortmund is also one of them. The Dortmund campus paradigmatically shows the characteristics of such planning: in a location detached from the city and not within walking distance, but only accessible by car or rail; exclusively university uses, no functional diversity as in the city; separation of car and pedestrian access and thus loss of an entrance side of the buildings facing the street; free-standing structures in the terrain and thus a lack of public space. With all these drawbacks, from the town planner’s point of view, Dortmund can be ruled out as becoming a university city.

From campus to city

Now, the IBZ is the opposite in every respect: it faces the street, forms a façade towards the street, and thus shapes the public space. It communicates with this public space in an appropriate urban manner: A shop window allows glimpses of the manifold public goings-on inside; at the same time, this shop window – positioned behind the stage of the event hall – affords views out of the building into the street space. With this stage view of the town, the IBZ is reminiscent of the famous Renaissance stage designs of a Serlio or Palladio, in which the stage prospect is designed as an urban space with foreshortened perspective. The view in Dortmund is still some way from such momentous beauty, but perhaps the window that has now been created will raise to some extent the aspirational standard of the outward impression of Emil-Figge-Strasse.

Dortmund Technology Park as an urban feature

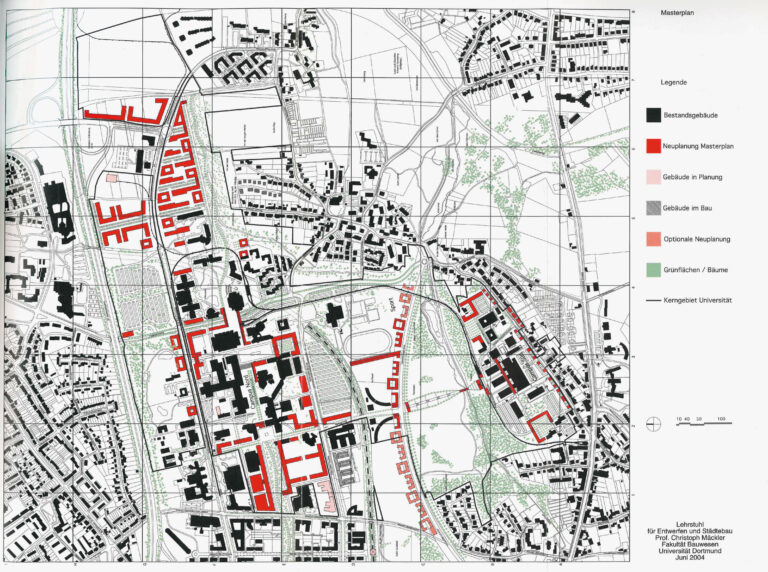

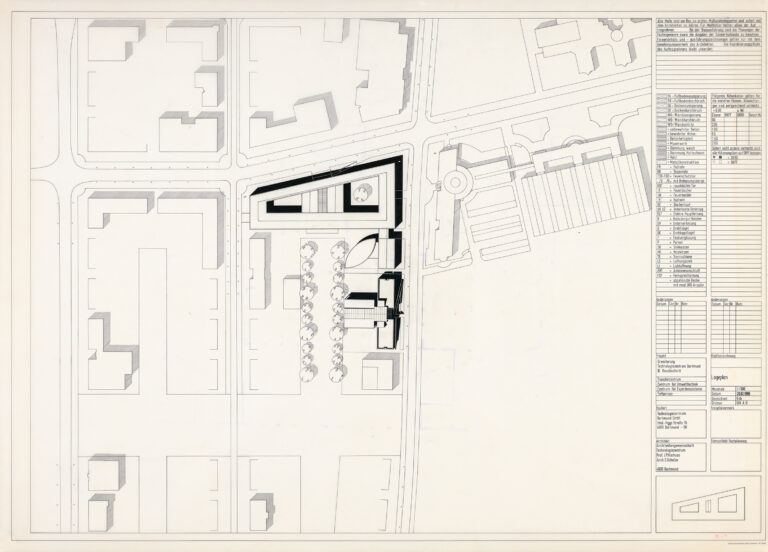

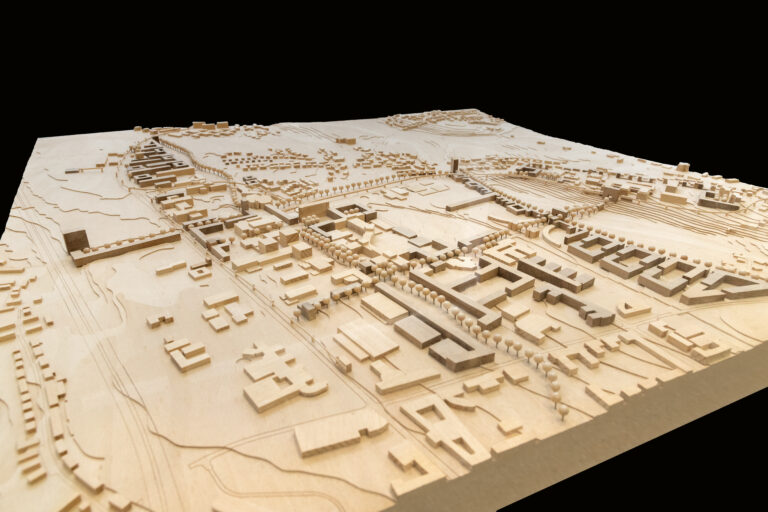

However much the IBZ contrasts with the building structures (#TU Dortmund, EF 50) of the TU Dortmund University campus, it is embedded in a more comprehensive strategy for the Europeanisation, urbanisation, indeed, one could say civilisation of the campus grounds. The departure from the ideal of the car-friendly city, as it characterises the campus, with its separation of car and pedestrian traffic, came with the creation of the technology park immediately to the west of the TU Dortmund. A competition held by the city of Dortmund in 1986, in which the architect Oswald Mathias Ungers was one of the participants, and of which three competition models are kept in the Baukunstarchiv NRW, resulted in a design that envisaged a classic grid-like street network with tree-lined avenues and buildings along the edge of each block. More than this, the plan demanded a uniform positioning of these commercial buildings behind a front garden, a uniform height as well as a uniform design in red brick. It was precisely these strict urban planning and architectural specifications that fuelled the success of this technology park. Contrary to the widely held opinion that only the greatest possible design laissez-faire would suit business, it proved here that the certainty of knowing the context in which one’s own building would later stand helped rather than hindered the investments of the various companies. Despite this visible success with what is perhaps Germany’s most beautiful industrial estate, the idea of establishing design rules for industrial estates still seems unthinkable to most local politicians today.

Design principles of architecture and urban development

This embracing of the rules of classical urban planning with a street network, perimeter block development and the creation of public space with street façades in Dortmund Technology Park took place by no means in a vacuum. It had been driven forward with global effect by the International Building Exhibition (IBA) in Berlin in 1987, planned from 1978 onwards, whose protagonists were at the same time closely linked to the planning in Dortmund. Ungers, whose competition entry became formative for the execution plan of Dortmund Technology Park, was initially envisaged as one of the directors of the Berlin IBA. Kleihues, in turn, was given this position and shaped the urban philosophy of the IBA Berlin with his strategy of “critical reconstruction”. He had already been developing the ideas for this as a professor at TU Dortmund University from 1974 onwards – not least at the Dortmund Architecture Days at the Museum am Ostwall, today’s Baukunstarchiv NRW, to which he invited renowned international architects and discussed basic design principles of architecture and urban development with them. It therefore seems almost logical that this Dortmund-Berlin co-production also resulted in a building in Dortmund Technology Park by Kleihues, whose estate is also in the keeping of the Baukunstarchiv NRW.

Fronts and backs

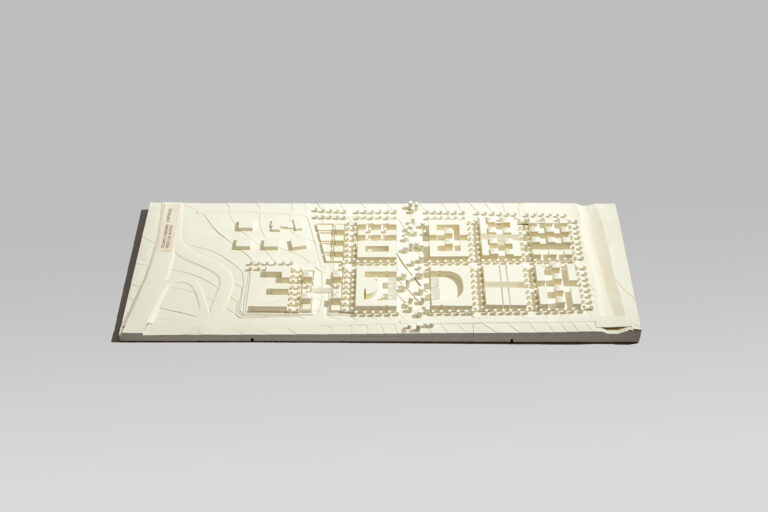

With its brick façades defining the streetscape and its steel columns announcing its entrance, the Technology Centre built from 1988 to 1992 is a paradigm of the new orientation towards classical urban planning principles with a local flavour. This “urban spirit” was in turn taken up by the master plan for the development of the TU Dortmund University campus, which Christoph Mäckler drew up in 2004 from his chair of urban planning in Dortmund on behalf of the university’s directors. The consolidation of the spatial edges on the central pedestrian esplanade, but above all the creation of urban-space-forming buildings on the surrounding streets, were the revolutionary steps of this plan, which, as it were, placed the campus, the embodiment of car-oriented planning, on the solid ground of compact urban planning. He also took the design of the adjacent Technology Park as a model and recommended the use of red brick or red plaster on the façades of new buildings. He subsequently revised and developed the plan several times. For example, the sweeping perimeter development of the traffic-friendly curved Universitätsstrasse was dropped because this road itself – designed as a tangential road encircling the city – had meanwhile been abandoned.

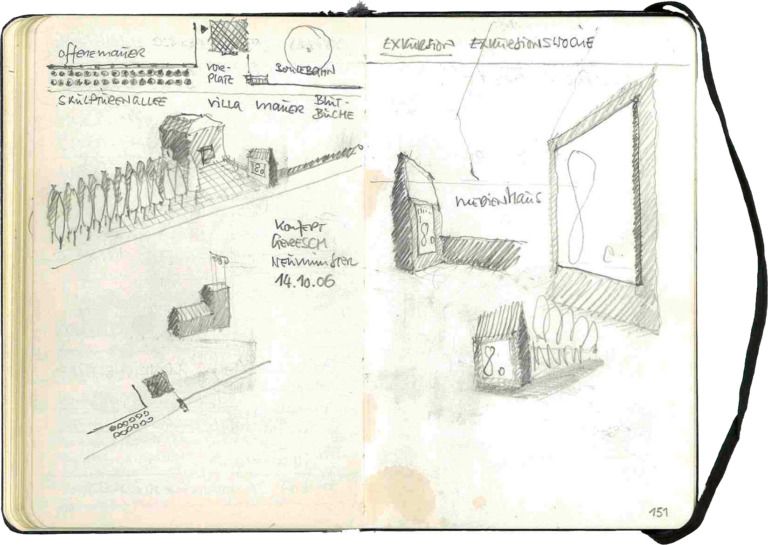

International Meeting Centre

As an urban feature, the IBZ now slots strikingly into this plan in exemplary fashion. It was built between 2008 and 2009 as a gift from the Society of Friends of TU Dortmund University to mark the university’s 40th anniversary. Martin Cors and Imke Woelk and their architectural office in Berlin were responsible for the design and execution. The design idea came from Christoph Mäckler. His sketches show beautifully how he was not only concerned with a functional and structural building solution in this design for a house that was to welcome the world to TU Dortmund University. For he regarded the design of the street space as not only an aesthetic task, but was also about finding conspicuous forms. The small building should be able to show that it promoted international exchange.

Gesture of invitation

Internationality finds expression in a row of flags crowning the façade overlooking the street. Not linguistic means, but an architectural design device, familiar from the frequent use of rows of flags at international institutions, was to communicate the message. The gesture of invitation and at the same time the gesture of openness were made by a huge showcase window, which in its size far surpassing its practical function immediately reveals its symbolic character. The tower-like elevation of the building towards the street, rising above the building proper and necessary for the installation of the window, already indicates that it is not just a matter of illuminating a room, but also of presenting a window: a window of the building onto the street, a window of the university onto the world.

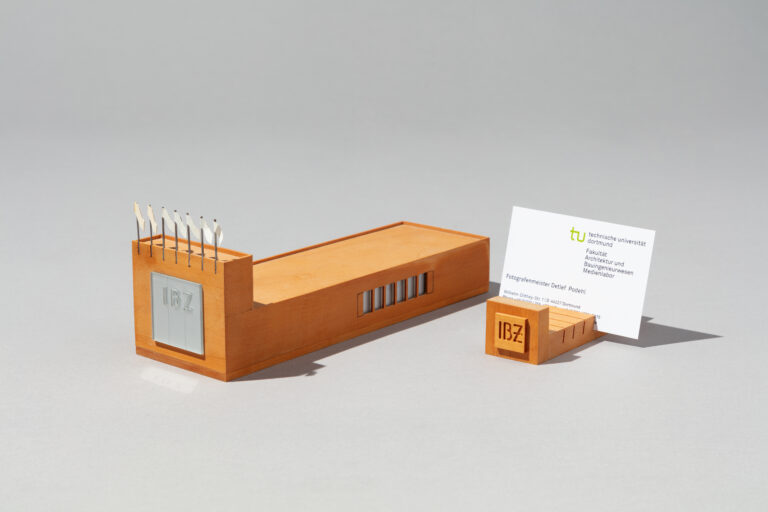

The building as a building block

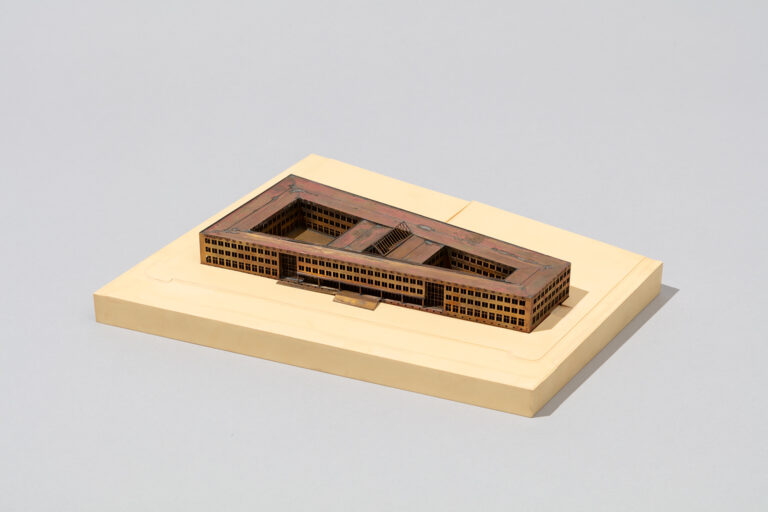

The fact that this building, which seems to have been designed entirely from its façade, from its flat delimitation of the wall facing the street, has at the same time become a coherent structure with a sculptural form, is illustrated by the models made at the model building workshop of TU Dortmund University. One presents the building as a structure that can be used in a variety of ways, like module from a kit. The other turns the building into a small design object, a piece of furniture for everyday office life. The scaled-down IBZ becomes a holder of business cards in which the architect can store a variety of international contacts in his office. The small building with its red combed plaster, taking up the colour scheme of the Technology Park, and its ecologically sustainable solid brick construction swiftly received an award from the BDA Dortmund-Hamm-Unna for good building in 2010.

A lively city quarter

It is a built model for the ongoing evolution and design of the TU Dortmund University campus: away from car-oriented traffic planning towards traffic-linking urban development; away from formless remnant spaces towards designed street spaces; away from faceless building shells towards distinctive building façades. If one develops this urban design idea further with a mixture of functions, a road network connecting the city and perhaps one day even an architecturally striking appearance of TU Dortmund University as the entrance to the city on the A40, converted into an urban avenue, then the monofunctional campus of TU Dortmund University could one day become a lively city quarter – the University City of Dortmund.

The present text was first published in: Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, Wolfgang Sonne, Barbara Welzel (ed.): Bildung@Stadt_Bauten_Ruhr, Dortmund 2022, pp. 184–199.