Between a thousand plateaus

Christos StremmenosIf one examines the documents on Kunstmuseum (Museum of Art) Gelsenkirchen from the estate of the architect Albrecht Egon Wittig in the NRW Architecture Archives, one finds a tradition typical of the late 1970s and early 1980s: ink design drawings laid out with transparencies in patterns and colours, grand designs and minor eccentricities sketchily captured on fine tracing paper or scraps of paper, a lively correspondence that unfolds its polyphony in typewritten documents, numerous series of photographs taken by the architect at different times to document progress on his museum from 1982 to 1984 in the centre of the Buer district of Gelsenkirchen.

Black Box Museum

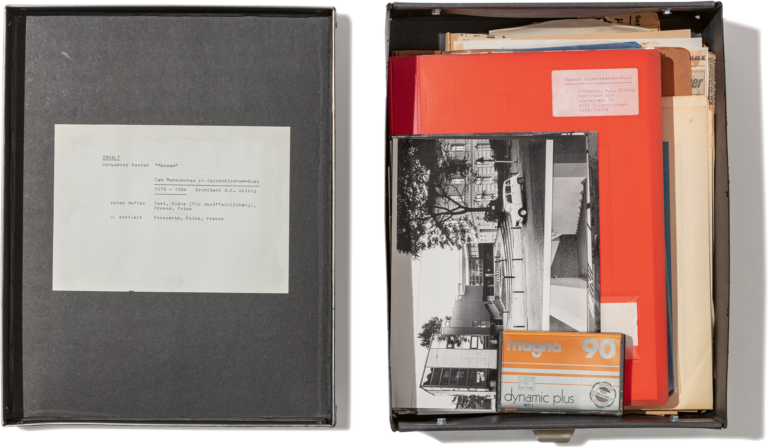

It is a legacy in mainly manually produced media that achieve their presence through their palpability and tell of an era shortly before the digital established itself in the means of architectural production and design. In the midst of this physical legacy, one comes across what at first appears to be an unassuming box, which the architect has labelled “Schwarzer Kasten Museum” (Black Box Museum) on the inside of its lid.

Opening the box of black-dyed cardboard reveals a remarkable collection, an archive within an archive: various photos and photo series, design drawings in reduced form for presentation purposes, presentation folders assembled like montages, lists of modernist museum buildings that probably served as inspiration during the design process, and numerous articles meticulously cut out from daily newspapers and magazines, illustrating the resonance in the media of the time.

It is not a systematically structured archive that lays claim to completeness. The architect is consistent in this respect in his conventional filing of his drawings and documents. What has been created here is more a testimony to his collection, reflection and documentation, but also of inspiration and distraction with regard to his own project. It is a consolidation of things that tend to have the value of the exceptional and which the author presumably continuously extended with different motivations and found objects. This composition of the box’s contents, seemingly erratic at first glance, calls for them to be physically spread out so that they can unfold their effect and structure.

No reading in the conventional sense is required. The contents of the box know no beginning, no end, no first and no last object, no first page, no last; initially, neither hierarchy nor framework can be discerned that holds the different levels of information together.

Ambiguities

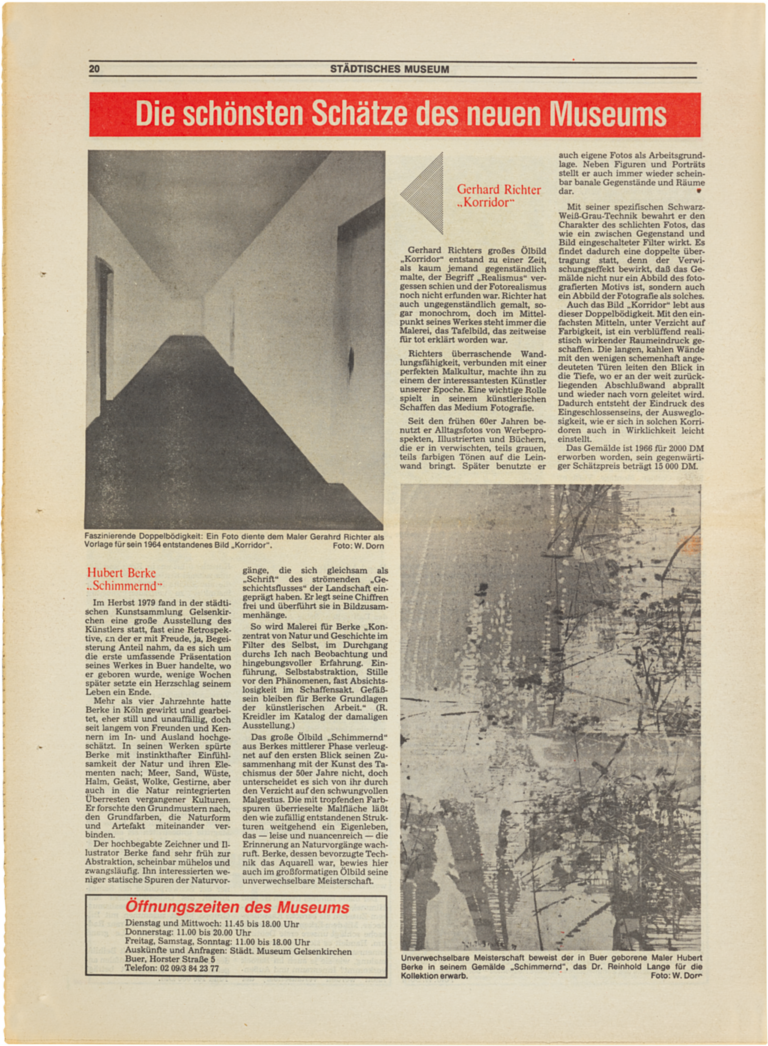

In this ambiguity of a supposedly protective exterior of the black box and an interior unfolding in several layers, the “Black Box Museum” that Wittig realised in Gelsenkirchen can also be interpreted. Approaching the museum building on Horster Strasse, a main traffic artery of the Buer district, one encounters, as shown in the black-and-white photograph taken shortly before the building’s opening, a superficially intensely sombre nested hybrid figure that at first seems to integrate itself amorphously into the urban space. The dark metallic impression is due to the façade surface composed of profiled copper sheets. The architect deliberately chose this material because, unlike concrete, it ages “gracefully”, as he put it in a special edition of the Buersche Zeitung in 1984 to mark the opening of the museum. Given the properties of copper, the chosen façade material, a process of darkening that takes place naturally over the years can be likened to dignified ageing, beginning with a reddish brown and gradually transforming the building into a deep dark grey. And this suggests a forced transformation of the building into a “Black Box Museum”, though this is perhaps merely a subconscious intention on the part of the designer.

This interpretation refers to the contrast with the gleaming white-rendered Villa Pöppinghaus built in 1893 adjoined by the dark building. This Wilhelminian mansion housed Gelsenkirchen’s municipal art collection from 1957 until the opening in 1984 of the extension long discussed and demanded by the citizens of Gelsenkirchen. Set back from the road, the new structure and the historic building together spatially define a forecourt acting as a welcoming gesture from the road to the museum, with a fountain and steps leading up to it.

A world unfolded on several plateaus

Set in black frames, transparent incisions in the dark nested figure offer passers-by casual glimpses from the busy urban space to the world of art and give a first impression of the complexity of the “Black Box Museum”. When one finally enters the black box through the transparent opening, which visibly reveals the entrance situation to those outside, a world unfolding on several plateaus reveals itself to visitors on the inside, inviting them to stroll along galleries and staircases.

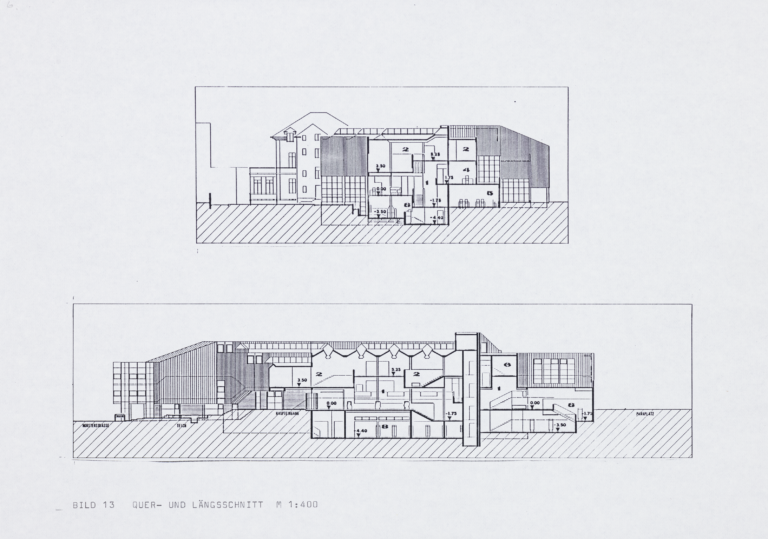

As can be seen in the two sectional drawings, Wittig designed a complex space of paths inside, like a trail through the house, with spatially offset plateaus and gallery levels linked together by stairs: corridor constructions.

Each plateau becomes a small section of the collection. This spatial structure of the presentation on different levels in the space opens up possibilities and positively encourages the placement of collection pieces not in isolation, but always in a manifold network of relationships to other works, to plateaus, to insights into a reciprocal entity and to views of the city.

No singular image is capable of capturing this hybrid spatial structure in its entirety and depicting it two-dimensionally. Some examples of campaigns undertaken by the architect or the municipality can be found as photo series in Wittig’s estate, which attempt in several shots to document the tour of his building.

Deconstructed Corridors

In one of these black-and-white photographs, we come across an oil painting by Gerhard Richter on the highest plateau of the museum, affording us insight into an entirely different experiential space. In his 1964 work “Corridor”, the artist depicts a strictly linear, one-point perspective space that could hardly be more different from the multi-perspective space in which it is presented here in Gelsenkirchen: an access space entirely limited to its function, bordered by white walls and a strictly axial corridor. Illuminated in bright light, the deserted corridor, which here in this mode of presentation seems to be buried in the exhibition wall, lifts us out of space and time in a remarkable fashion. The lack of a view at the end of the corridor and the lack of openings in the side walls underline the hopelessness of the situation. It is not a space of abundance that we look into here; it is much more a space that limits people’s freedom of movement and action to a minimum.

From today’s point of view, it may seem surprising, but this space of mobility devoid of prospect that limits all communication and has its origins in the military and monastic buildings of the Middle Ages and was widely used in large-scale complexes during absolutism, not only made a triumphant entry into the architecture of the time in the 19th century as a system of circulation and order, but even advanced to become the space of modernity, as Stephan Trüby describes in his work on the “Geschichte des Korridors” (History of the Corridor). The corridor became the spatial manifestation of a modernity committed to the Enlightenment, which, in the disciplining effect of its corridors, pursued an educational mission aimed at preventing any spread of contagious diseases, behaviours or ideologies. Passageways and corridors of this kind channelled a belief in progress that sought, in a guiding manner, to improve the human being within the norms of a new civil society.

Trüby describes Kafka’s hallways and corridors as the “material arm” of the “Kafkaesque”, which are penetrated by an invisible but ever-present bureaucratic apparatus and which the author stylises as a recurring motif in his novels as a “continuous trail of the sinister”.

While in Kafka’s corridors the walls are in a state of disintegration that is tantamount to a perforation, Wittig’s concept for the Kunstmuseum is a “corridor space” split open and even deconstructed. His walls have been largely dissolved and distributed in the space at different heights and re-emerge as set pieces along the way, forming varied sequences of spaces. As in Kafka’s work, we see ourselves transported into a trail, albeit not a sinister one, but one that can be experienced and opened up.

Between Plateaus

In their work “A Thousand Plateaus”, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari proposed a method of rhizome-like access to knowledge contrasting with a tree-like, genealogically and hierarchically structured model of science. The tree model generates knowledge about processes of reproduction and division and, with its binary dichotomous properties, represents “a logic of copying and reproduction”, which can always be traced back to a main trunk and root. It is a somewhat closed system that denies access to a midst, a middle.

A rhizome, on the other hand, is composed of plateaus that spread out and occupy space. A rhizome is “a map and not a copy”. Access to the material and immaterial world is to be sought in an in-between – between plateaus – and detected in structures of a middle. From each plateau, lines can be drawn to other plateaus, which can be likened to imaginary transversal strands and corridors in space and which in turn refer to other plateaus. The rhizome method of reading knows no beginning and no end; it only knows plateau-like entrances and exits into an in-between.

But Deleuze and Guattari do not mean a supposedly simplistic dualism in the form of copy versus map. On the contrary, they always recognise the one in the other. A similar interpretation can also be seen in Wittig’s approach. The corridor, a path-space typology that can be found in countless buildings as a copy in variations, is translated into the cartographic in Gelsenkirchen through plateau-like unfoldings. The museum itself becomes a map of a topos composed of plateaus, a topos that encourages strategies of appropriation in spatial structures by enabling us to repeatedly draw imaginary transversal corridors between things. If you add to the interlacings on the plateaus the prospects opened up by the artworks displayed on them and the recurring views of the city, then you are truly moving between a thousand plateaus here inside Gelsenkirchen’s “Black Box Museum”.

The present text was first published in: Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, Wolfgang Sonne, Barbara Welzel (ed.): “Und so etwas steht in Gelsenkirchen…”, Kultur@Stadt_Bauten_Ruhr, Dortmund 2020, pp. 118–133.