“From Turku to Essen”

Christin RuppioThe example of the Aalto-Musiktheater (Aalto-Theatre) in Essen illustrates the fascinating interplay between the built environment and the architecture archive. While the theatre building suggests – above all from its name, but also from its characteristic, organically curved forms – that it was completed by the Finnish architect Alvar Aalto, the estates preserved at the Baukunstarchiv NRW tell a different tale. Although the story of the building begins in 1959 with a successful competition entry by Alvar Aalto, it was not executed until 1983 to 1988 by Harald Deilmann. It is therefore the treatment by one architect of another’s design, years later and under different circumstances: “From Turku to Essen”.

“Preservation of the artistic and architectural idea”

The fact that these are two very different approaches – also reflecting the different periods in which they emerged – can be seen from the archived documents. Instead of folders of sketches and plans, as typical of Aalto’s papers in other archives, the Deilmann collection on this project confronts us with boxes full of microfiches and photographs of the completed building. Also included are a number of copies and photographs of Aalto’s design. At first glance, this juxtaposition suggests that we have on one hand Aalto’s creative spirit – with expressive drawings – and Deilmann’s meticulous technical execution on the other. And yet Deilmann’s contribution must be acknowledged as being much more than a mere implementation of an already complete vision. Since Deilmann regarded the “preservation of Aalto’s artistic and architectural idea” as the overriding principle for the project, he had to restrain his own personality as an architect. Nevertheless, in addition to the necessary adjustments to building regulations, Deilmann implemented some changes that were significant for the building and its use. The improvement of the room acoustics, which makes the Aalto-Theater one of the most popular opera houses in the German-speaking world, deserves special mention.

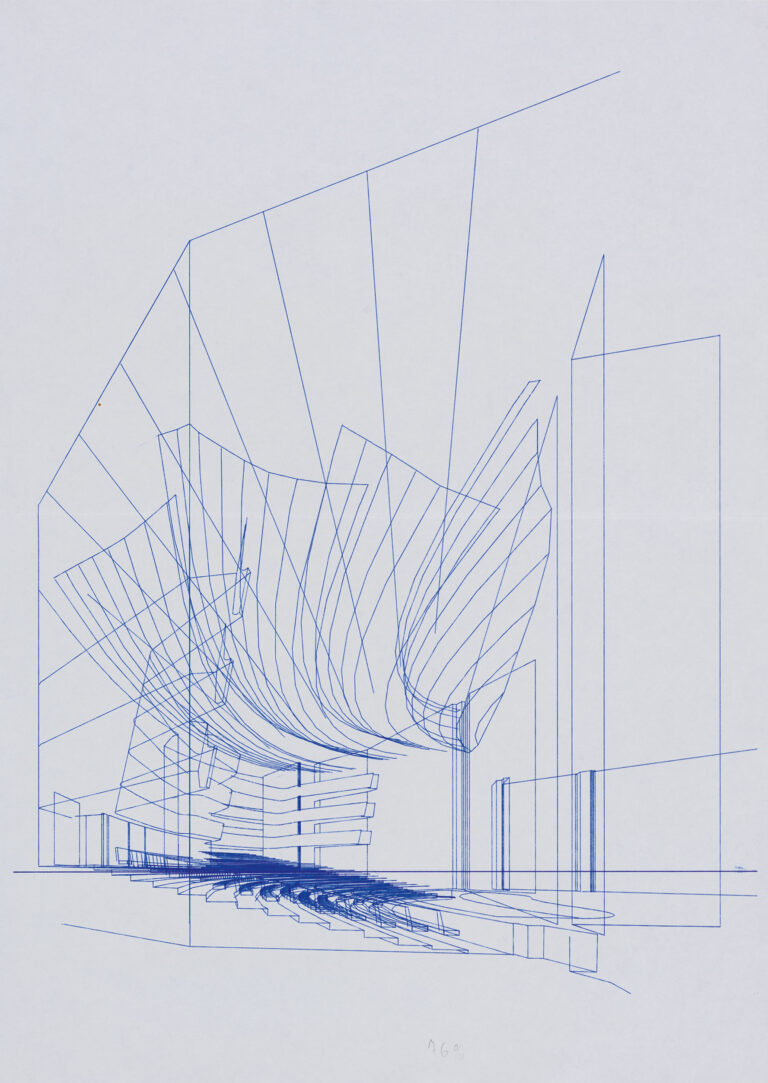

A sketch swiftly executed

The archive contains an interesting sheet on this, a computer-generated sketch of the auditorium. At first glance it could be a drawing by hand, but a closer examination soon reveals it to be a computer-aided graphic. No hand has guided a pencil on the sheet, and yet it resembles a sketch swiftly executed to make sense of the effect of the acoustic elements installed on the walls and ceilings. So even though Aalto’s design had already mapped out Deilmann’s path for execution of the building, he intervened at crucial points in order to create a top-quality theatre.

Responsible for the implementation of the versatile stage equipment was Adolf Zotzmann, thus ensuring that the venue is equipped both for large concerts and more intimate performances. Movable walls and platforms can be used to create different stage depths, floor levels and inclinations, giving the appearance of a transition from the audience space to the stage space. It is not a pure proscenium stage, although a complete elimination of the separation of audience and stage space was not intended.

Asymmetrical arrangement

Deilmann was convinced that the latter could not be achieved. The amphitheatre had already been one of the most important sources of inspiration for Aalto’s design. This model was given a new dynamic and spatial effect in Essen with the asymmetrical arrangement of the seats – 15 seats on the right and 21 seats on the left. Deilmann’s implementation today seats 1125. Among proponents of the abolition of spatial divisions in the theatre – including Werner Ruhnau – the design met with resistance, and some voices even questioned the purpose of a new music theatre when the Musiktheater im Revier (#Musiktheater im Revier) was only a few kilometres away.

Not only a temple of the Muses

Although a complete break with the traditional conception of the theatre was not on the agenda, Deilmann stressed in 1988 that theatre design nevertheless had to meet new demands. Instead of being venues for the aesthetic edification of a certain class, the current aspiration was to create places of encounter and discussion for broad sections of the population. A societally important aspiration was already evident in the text of the announcement of the competition in 1958: “A second theatre is needed for the population, which has now grown to 720,000. It is to be built on a favourably situated site in the northern part of the Stadtgarten park near the Städtischer Saalbau (concert venue), on the corner of Huyssenallee, Rolandstrasse and Rellinghauser Strasse. Planned is a venue that will primarily serve musical theatre (opera and operetta) and, on occasion, large-scale theatre productions. It should satisfy the spatial and technical requirements that are considered necessary today. Particular importance is attached to effective integration into its urban surroundings and good traffic arrangements.” Competition entrants should therefore not only create a temple of the Muses, but above all present solutions as to how it is to be linked to its urban surroundings.

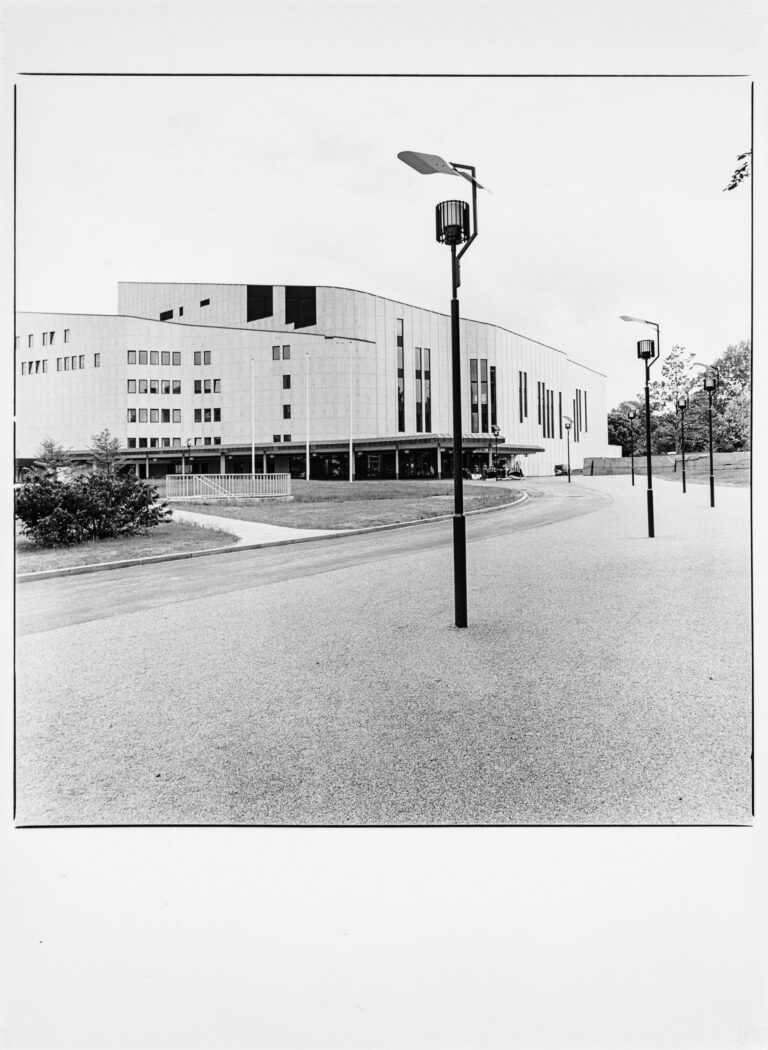

Façade and a network of paths

The relevance of the building’s location and access to it can still be clearly seen today. The sweep of the curved west façade seems to draw visitors in; the flat south façade appears more closed at first, but opens up to the park via a projecting terrace. The greenish copper roof and the natural stone façade blend harmoniously with the greenery of the adjacent city park – here, too, Deilmann had to deviate significantly from Aalto’s plan of a white marble façade, which would hardly have withstood the regional weather and air conditions. While motorists can use the multi-storey car park directly in front of the entrance and drive up to the covered foyer, the theatre can also be easily reached on foot through the park or by public transport, which directly serves the east façade. The different forms of mobility are thus spatially separated from each other, but converge at the theatre via a network of paths – either from the street or through the park.

An overall plan ready for approval

Initially, only architects resident or born in Essen were admitted to the competition, but some architects from outside Essen were also invited. In August 1959, the jury met at the Museum Folkwang to review the designs on display and ultimately awarded the contract to Aalto. Aalto made the adjustments noted by the jury in 1964 and submitted an overall plan ready for approval. At the time, however, the city of Essen was giving precedence to other building projects, such as housing and schools, so that this original plan was not implemented. After the project was resumed and Aalto’s design was modified in 1974 – which he undertook in consultation with Horst Loy, the architect involved in the old building of the Folkwang Museum – the project came to a standstill for a second time.

White and indigo

The first time around, it had been the more pressing social building tasks that made it impossible to finance the theatre. The second attempt was shaken by Aalto’s death in 1976 and then also came to a temporary halt due to the advance of structural change in the region and the resulting constraints. The strongly felt need for a new theatre building for Essen remained, however, and led to the founding of the “Gemeinnützige Theaterbaugesellschaft” (non-profit theatre construction society). The society then commissioned Harald Deilmann to continue the project in 1981. Twenty years earlier, Deilmann had been on an excursion to Finland with several colleagues and also visited Aalto’s studio. The latter had a visitor from Essen with him to discuss the construction of the theatre and invited Deilmann and his colleagues to attend the meeting. At the time, Deilmann thus – completely unwittingly – gained insight into the progress of the Essen project that he would himself complete so many years later. He was advised by Aalto’s widow Elissa Aalto, who had a major hand in her husband’s designs. It is also thanks to Elissa’s involvement that the interior of the theatre – with its interplay of white and indigo in different materials such as marble and textiles – was realised exactly as Aalto intended. All this speaks so clearly to Aalto’s design language that Deilmann’s significant contribution has been barely noticed by the public.

The present text was first published in: Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, Wolfgang Sonne, Barbara Welzel (ed.): “Und so etwas steht in Gelsenkirchen…”, Kultur@Stadt_Bauten_Ruhr, Dortmund 2020, pp. 222–237.