Municipal monumentality

Town halls and squares in the towns and cities of the Ruhr

Wolfgang SonneIf there is one central building task that is primarily intended to represent the urban community, it is that of the town hall. From the early Middle Ages, church towers and city walls defined the appearance of the town and its skyline. At the height of the Middle Ages in Europe, these were joined by the town hall as a monument to the increasingly powerful and independent municipalities. As a flourishing region with Hanseatic towns and free imperial cities on the Hellweg trading route, the Ruhr region also played its part in this trend.

Then, in the middle of the 19th century, in the course of industrialisation, the towns and villages in the Ruhr region began to expand into large towns and cities – a process that has continued in various waves and different ways up to the present day. Characteristic of this process is not only the enormous expansion of urban areas combined with a correspondingly huge increase in population, but also the differentiation of urban life with a variety of new institutions and associated building tasks. The purpose of architecture in particular has also been to create a metropolitan atmosphere with its intentionally urban character – not least with the central building task of the town hall with the urban square.

In his 1913 book “Die Architektur der Großstadt” (“The Architecture of the City”), Karl Scheffler illustrates the importance attached to the activities of the municipalities in the shaping of the modern city: “Such a shaping of the latent metropolitan idea, however, demands a population whose consciousness is deeply infused with its historical mission; it calls for municipal administrations guided by a sense of its own importance to achieve goals on a grand scale and state governments that govern not against the city, but in close alliance with it. Without the monumental shaping of the system of self-government […] there cannot even be a beginning of any significance.”

The immediate architectural expression of this system of self-government was the town halls of the growing cities. In entirely practical terms, the rapidly expanding administrations needed greater space; at the same time, however, they needed a new quality of self-presentation in the urban space in order to lend public expression to their new role. As cities, the towns of the Ruhr thus gave themselves new monumental hubs and built suitably prestigious town halls with public squares.

It was almost typical of the public building projects of the municipalities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that they not only created such monumental public buildings, but often combined town halls with squares and thus contributed to the design of the urban space: public space and public building were aspects of the same task. This planned reformulation of the municipal public sphere with a new town hall and square is especially evident in the up-and-coming industrial cities of the Ruhr, some of which did not have a suitable historical town hall & square constellation. This municipal monumentality began during the period of the German Empire, continued – often with the direct continuity of existing projects – during the Weimar Republic, and came to an abrupt end when the National Socialists seized power in 1933. Democratically legitimised municipal organisations were no longer to play a role in the Führer’s state. Precisely this combination of town hall and square is a remarkable example of a tradition of prestigious monumental public architecture in the service of the democratic state that was terminated by National Socialism and only hesitantly resumed after the Second World War.

Town halls in the major towns along the Hellweg trading route

The history of the town hall buildings of the modern towns in the Ruhr region in the age of industrialisation cannot be told without also mentioning the town hall building traditions of the Middle Ages and the early modern era. Medieval town halls in all the large towns on the Hellweg are now conspicuous by their absence, having been demolished in Essen in 1840, in Duisburg in 1843 and 1944, in Bochum in 1862 and in Dortmund in 1955. Yet, not infrequently, the reference to municipal medieval history was a prominent feature of metropolitan development and town hall construction, especially in the age of industrialisation.

Paradigmatic for this is the history of Dortmund’s town hall buildings. In the Middle Ages, Dortmund was not only the largest and most important town in the region, but it also had one of the first grand town halls in the Empire as it then existed north of the Alps. It probably owes its proclaimed status as the “Germany’s oldest stone town hall” to its prominent mention in Otto Stiehl’s great 1905 monograph on the German town hall in the Middle Ages. At the beginning of the book, it is highlighted as “the oldest of the town halls still in existence”, a status it unfortunately can no longer claim today.

Dortmund’s town hall, which was initially built before 1241 as the seat of the Count of Dortmund before being taken over by the town council shortly afterwards, is a good example of the development of the typical town hall building in Germany. Town halls only became possible when the towns, by virtue of their economic might, gradually became able to free themselves from the rule of the bishops or feudal lords in the course of the 12th and 13th centuries and were granted their own rights by the latter or by the emperor. Alongside churches, castles and palaces, town halls constituted a new type of prestigious building in the Middle Ages.

Here, the multifunctional requirements are packed into a compact cuboid covered by a gable roof. On the ground floor, behind porticos for the administration of justice, there is a large room dedicated to trade. On the upper floor is a large hall for council meetings. Staircases are located on the outside of the building, which means that the different floors can be used independently of each other and used for announcing council resolutions or court judgements. Like all subsequent town halls, it stands as a dominant building on the market square, facing it with its narrow gabled end. As a gabled building, it takes up the building type of the burgher house, which occupies a narrow plot, usually extends into the depths of the block and presents itself with an in some cases imposing gable façade. Dortmund’s town hall thus shows itself to be “primus inter pares”, demonstrating its uniqueness not only with its stone architecture in contrast to the half-timbering of the burgher houses, but also by adopting sacred ornamentation, in the tracery-filled blind arcades, for example.

But Dortmund’s town hall was not only of great importance for the medieval free imperial and Hanseatic city and the history of town hall construction in Germany. For it once again achieved prominence as the nucleus and point of reference of the industrial town that was evolving into a city. In the 19th century, the town hall survived several plans for demolition to make way for a larger new building. Ultimately, the town’s master builder Friedrich Kullrich succeeded in saving the building with a large-scale campaign by erecting the municipal hall that still exists today as an extension in a different location. The old building, which had been extended modestly in the meantime and whose dilapidated gable had undergone Baroque refurbishment in the 18th century, was upgraded by Kullrich to his own design with stepped gables and tracery windows in time for the emperor’s visit in 1899. As a painstakingly constructed “Middle Ages”, the old Dortmund town hall thus became the starting point of the modern city in the industrial age. Today, the only reminder of this in the urban setting is a modest plaque, albeit hung up in the wrong place.

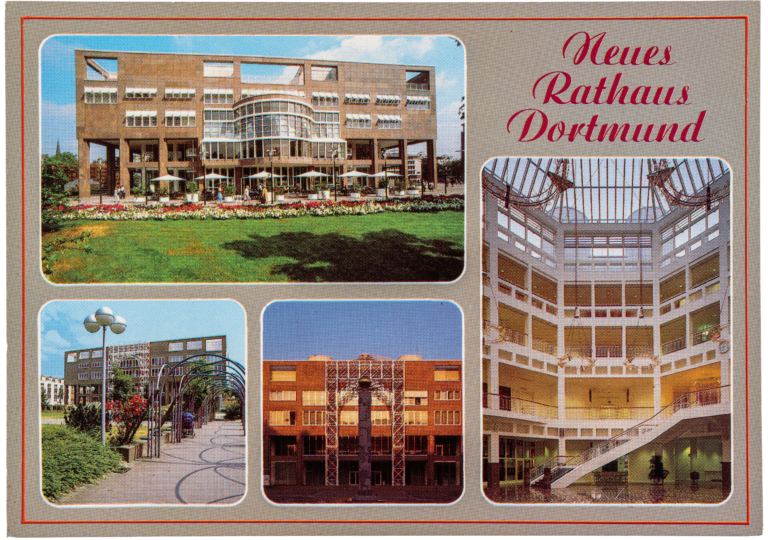

Concurrently with the renovation and partial reconstruction of the old town hall, Kullrich created the “Stadthaus” or municipal hall as a town hall extension to provide additional space for the increasingly demanding administration of the city and, with its stately Neo-Renaissance gable on the southern approach road to the city, also a new landmark in the urban environment. In the 20th century, the town hall’s building history continued with growing demands. Kullrich’s town hall was extended in 1928 by Wilhelm Delfs with a solid brick building with an inclined natural stone base, whose tower is both the town hall tower and an office tower. To the south of the old town hall, Dietrich Gerlach’s new town hall was built after the Second World War in 1954, welcoming visitors to the city as a ten-storey high-rise building on the Wall (rampart ring road) and the newly upgraded Kleppingstrasse. The glazed Berswordthalle has mediated between the two buildings since 2002. The ensemble is located on Friedensplatz, a space only created in 1989 and, thanks to the buildings around it, is now effectively Dortmund’s town hall square. Formerly occupied by buildings, the site rendered derelict by the war was not given its form as an urban square until the construction of the new town hall by Dieter and Ulrike Kälberer in 1980–89. Designed with exactly the same dimensions and shapes as the town hall building itself, the square thus demonstratively signals its affiliation to the town hall and hence the unity of public building and public space. With its emblematic gateway structure, the sandstone-clad town hall cube forms the western boundary of the square. Today, there are five town hall buildings on Friedensplatz, built over a period of more than a century. Despite its importance as the oldest surviving town hall north of the Alps, the medieval town hall at Alter Markt was pulled down unceremoniously in 1955 as a wartime ruin.

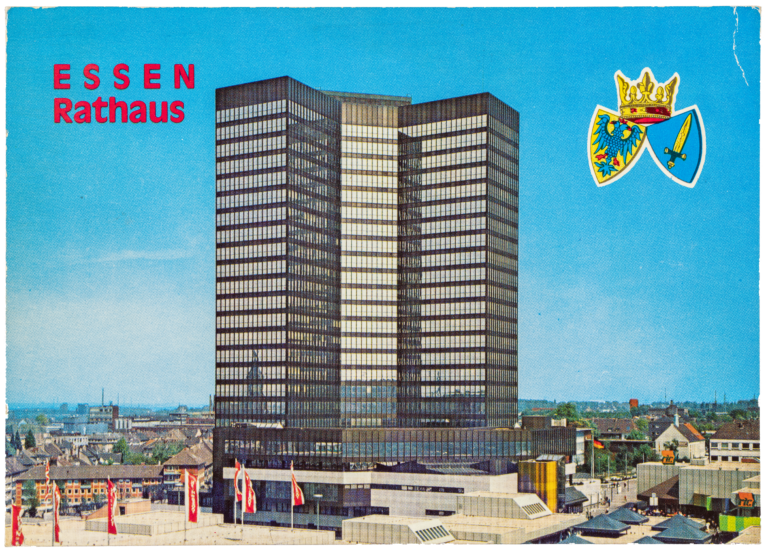

The history of Essen’s town hall buildings is also marked by multiple demolitions. After the citizenry had gradually acquired its own rights in the shadow of Essen’s Abbey, a “domus consulum” was first documented in a deed in 1301. With its side facing the market square, the town hall was a two-storey building with a market hall on the ground floor and a council chamber on the upper floor and thus conformed to the usual design. According to a rebuilding plan, the medieval building extended on multiple occasions was torn down in 1840 and replaced by a new Neoclassical structure in 1842. With great ambitions as one of the first major town hall projects of the imperial period, a competition was then held in 1874 for a new town hall building, erected by Peter Zindel and Julius Flügge in 1878–1884. To make way, the Neoclassical town hall recently put up had to be pulled down. Like many town halls in the empire, the new building with its Neo-Gothic forms again referred back to the Middle Ages – though less to the specific local tradition than to an idealised bygone era. This imposing, type-defining urban monument on the market square with its tower on the corner was seriously damaged during the war, but was then rebuilt by 1956 and a new wing was added.

Against this background, the building’s subsequent history seems grotesque. Less than ten years later, in a city history sell-off, the property was sold to Warenhaus Wertheim GmbH and the town hall demolished in 1964. As a result of this farce, the council was now without a town hall. Although a competition for a new town hall building was held in 1963, the new building to the design of Theodor Seifert was not completed until 1974–79 after several revisions. Since then, Essen has had Germany’s tallest town hall – but as a faceless office building in the style of Mies van der Rohe, it does without any significant decor and vanishes in the crowd of commercial office blocks. Thus, it can certainly be interpreted as a stern warning that radical modernisation combined with the deliberate negation of history is no use in shaping the identity of a modern city.

The history of Duisburg’s town hall buildings is also a story of loss. The “domus consulum”, documented in 1361 for the no longer free imperial town of Duisburg was located in a building that had evolved out of the royal palace on today’s Burgplatz. At the end of the 13th century, a market hall had also already been built on the market square, which was extended with a similar structure at the beginning of the 14th century. Its rectangular ground plan with a market hall on the ground floor and an assembly hall upstairs as well as stepped gables on both sides conformed to the now established town hall typology. The augmentation of the building by adding an extension was also typical of the evolution of the town hall in the late Middle Ages. With its stepped gables, the new town hall, built by Friedrich Ratzel on the site of the old town hall in 1897–1902 after a competition in 1895, adopted a feature from the neighbouring medieval market hall, the remains of which were cleared after its destruction in 1944. Today, it is commemorated by an outline sculpture erected after excavations in 1980. With its Romanesque, Gothic and Renaissance forms, Ratzel’s building reflects, as it were, development history with which the aspiring city adorns itself in lieu of an actual historical building. Despite damage during the Second World War, the town hall was subsequently restored and augmented with simplified elements. Duisburg’s town hall with its tower and gable is thus an imposing municipal monument from the period of industrialisation and Historicism.

Bochum’s town hall buildings also tell a tale of replacement and rebuilding. Bochum only gained its town rights late in the 14th and 15th centuries as part of the County of Mark, and a town hall is documented in 1461. Like all town hall buildings of the Middle Ages, the building replaced after fires in the 16th and 17th centuries stood on the market square, to which it opened on the ground floor with an arcaded hall. It was sold for demolition in 1862. The new metropolitan town hall by Karl Roth, built in 1926–31, presents itself as an austere administrative building in monumental stone. This, too, was preceded by a competition, but the city commissioned the design from the architect Roth, who had been so successful in building the town hall in Wuppertal-Barmen. By standing back from the corner of the block, this building again creates a forecourt that provides the appropriate stage for the city’s showpiece building. Three large and simple arches invite the visitor to enter the public courtyard modelled on Stockholm’s town hall. The building does without a tower making its mark on the urban setting; only a small ridge turret in the courtyard is reminiscent of this typical building element.

Medieval town halls

Despite the story of loss of the medieval town halls of the large Hellweg towns as well as those of Hamm, Unna, Lünen, Recklinghausen, Dorsten and Xanten, the Ruhr region today is by no means free of medieval town halls. Surviving in the smaller towns to the north and south of the Hellweg are a number of town halls dating from the late Middle Ages and the early modern period and mostly continuing the building types and forms of the earlier medieval town halls.

The oldest is the town hall in Rheinberg, dated by an inscription to the year 1449. Despite being refurbished and altered several times, its basic features have been preserved. As a free-standing rectangular three-storey block at the Marktplatz (marketplace), covered with a hipped roof and originally decorated with an all-round crenellated frieze, it physically emphasises – in contrast to the front- and side-gabled buildings – its autonomy. Like the town hall built a little earlier in 1438–46 in Kalkar, also in the Lower Rhine region, it is modelled on such Flemish town halls as those in Bruges and Ghent with their monumental blind arcades and towers. The tower and battlements are in turn architectural features of castle architecture that were employed as symbols of power on the town halls of Siena and Florence in around 1300, which were well-known in the Flemish cities due to their strong trading links. Incidentally, the Rheinberg town hall is the only medieval town hall in the Ruhr region to have a tower. However, the town hall tower still considered typical from today’s point of view was a by no means common feature of medieval town halls in Germany. The tower only underwent its type-defining upsurge with the new town halls of the growing industrial cities of imperial Germany, which were mainly modelled on the imposing examples of medieval Flanders and used the tower as an architectural means of achieving visibility and dominance across towns and cities.

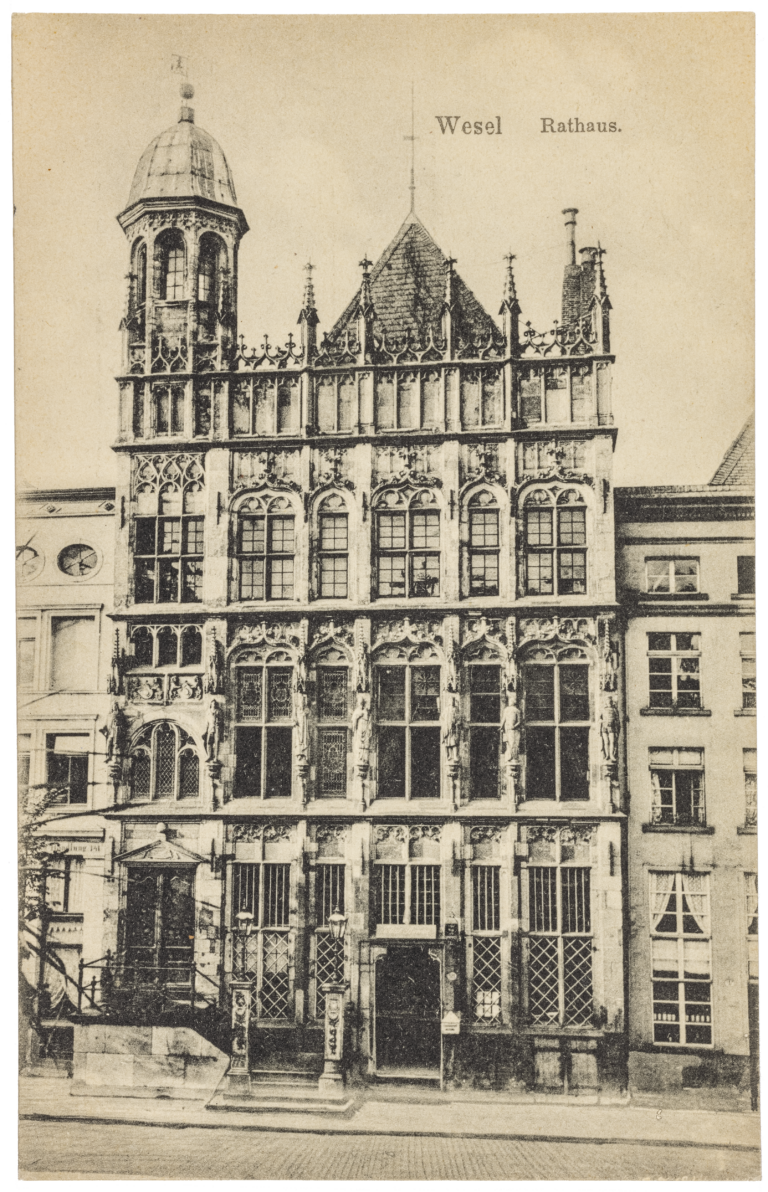

The town hall in the Hanseatic city of nearby Rhine-side Wesel also follows Flemish models. Here, however, it was not so much the building type as the building ornamentation that was distinctively adopted. In 1455, a new uniform symmetrical façade in the Flemish late-Gothic style was erected in front of the older town hall located in a row of houses on the market square. This façade, with its topmost horizontal arcading concealing the roof – also known as a blind façade because of its curtain character – was quite a common feature in medieval town hall construction, as in Lübeck or Stralsund for example, in order to give the town halls comprising a row of buildings a uniform appearance vis-à-vis the marketplace. A significant feature of Wesel town hall is its adoption of ecclesiastical building details such as windows with tracery and pinnacles for a crowning finish. The purpose here was not so much to sacralise the secular building, but rather to ennoble it through the use of grand architectural features, as was also the case with the above-mentioned town halls in Lübeck, Stralsund and Brussels as also with the town halls in Dortmund and Münster, which made use of the gable theme. Wesel’s town hall only gained its tower in 1700 when a staircase was added to the side in keeping with the style. Largely destroyed in the Second World War, the façade was only reconstructed in 2010–11. Thanks to its emphatic distance from the buildings on either side and the glass structure behind it, its character as a reconstruction seems to be highly overstated. Such museum-like aesthetic treatment would not really have been necessary, since the original was itself a façade placed in front of existing buildings.

After the Second World War, the municipality of Wesel regarded the construction of the town hall as a new beginning. Initially, the medieval town hall was not rebuilt, but a new building was erected on Hohe Strasse on the site of the destroyed Mathena Church. This building constructed in 1952–58 to the plans of Fritz G. Winter was a confident example of the town hall type with its distinctive corner tower. Its concrete grid façade took up the architecture of Auguste Perret, as for example on his new town hall in Le Havre. Despite its imposing appearance and its high-quality interior finish, the new town hall fell victim to a new department store built in only 1971. Instead, the municipality built itself another new town hall at Kornmarkt in 1970–74 to the design of Hentrich Petschnigg & Partner. Although the council chamber was given a special character as an octagonal structure, the ensemble of nondescript office blocks has not succeeded in making its mark.

The town hall in Werne, built in 1512–14 on the site of a predecessor building, is a late example of the rectangular town hall with a market hall and arcades on the ground floor and a council chamber above, which at the time had already been well-established for three hundred years. Like its Dortmund and Münster models, the Werne building has its gable end facing the marketplace; in contrast to these more distinguished buildings, however, it dispenses entirely with any ennobling façade ornamentation. In place of the upper steps of the already attached stepped gable, the building was given a triangular gable as a finial in 1561. As a stone building between half-timbered houses, it still vividly conveys the stately impression of even the older town halls no longer in existence in the Ruhr region.

The town halls in Schwerte and Haltern am See follow the same building design with arcades on the ground floor and a council chamber on the upper floor, but with the arcaded front along the building’s side. Unusually, Schwerte town hall built in 1547–49 faces not the marketplace, but the street leading to it. Its side overlooking the market, however, features an unadorned but striking stepped gable as well as two arcades whose pointed arches, together with the stepped gable, communicate the traditional image of the medieval town hall. The situation is exactly the other way round for the town hall in Haltern am See, built in 1575–77 and rebuilt in a simplified form after being destroyed in the war: its façade has eaves with arcades facing the marketplace, while a sequence of gables marks the various successively erected buildings in the side street.

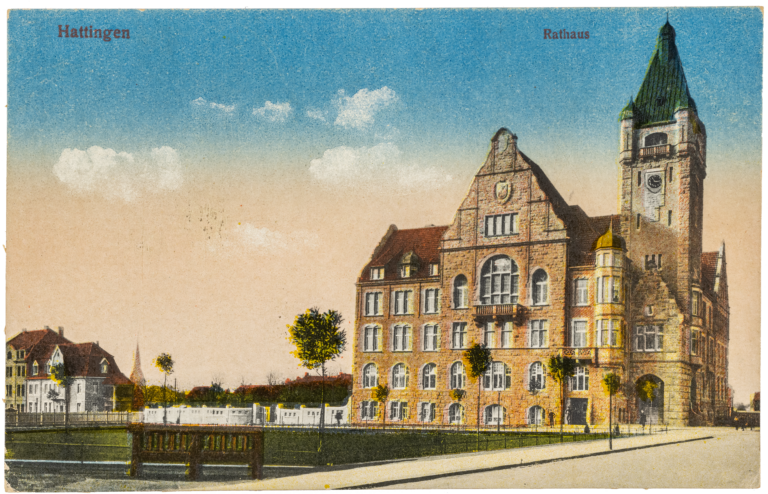

As a half-timbered building, the town hall in Hattingen, finally, is an exception in the Ruhr region. Its stone ground floor was a hall for meat traders in the marketplace. In 1420, the Count of Mark granted the townspeople the right to add a further floor for use as a town hall, which was finally realised in 1576. The originally erected pointed gable facing the marketplace was removed at the end of the 18th century and replaced by a hipped roof, giving the medieval-looking building a modern, more Neoclassical appearance. With its phases of building history, Hattingen town hall finely illustrates the combination of a market hall with a council chamber and courthouse, which was characteristic of the medieval town hall. For the growing industrial town of Hattingen, a new town hall designed by Christoph Epping was erected in 1909–10 at the new Rathausplatz (town hall square) north of the Old Town. As a picturesque corner house ensemble, with its towering Renaissance gables and dominant tower, it was an example of a building type widespread during the period of the German Empire, with which many towns created impressive public structures referencing their medieval and early modern history.

In Hattingen, one can thus trace the leap from the prestigious town hall building of the Middle Ages to the prestigious town hall building of the Modern Age, a leap thoroughly typical of towns in the Ruhr region. However, the 17th to early 19th centuries were not entirely “town-hall-free”. Several town halls were refurbished or replaced by new Baroque or Neoclassical buildings. Since these mostly small and modest structures were in turn demolished with the industrial expansion of such cities such as Bochum, Hamm, Essen and Lünen, almost nothing remains today of this historical layer of the urban fabric. Only in Dorsten, for example, does the town hall of 1567 show its recently restored appearance of 1797.

Town halls of industrial towns and cities during the German Empire (1871–1918)

For the cities of the Ruhr region growing rapidly as a result of industrialisation, the town hall competition in Essen in 1874 then marked the beginning of a town hall building boom that echoed the erection of new, monumental town halls all over the imperial Germany. Shortly after the erection of Essen’s type-defining new town hall, Werden to the south also built a new town hall in 1879–80 to the design of Wilhelm Bovensiepen. It gained its present form during the extension in 1912–13 by the Essen architects Grosskopf and Kunz. With its gables and oriels in the German Renaissance style, it resembles a large town house; the ridge turret, however, gives it a clearly public face. The town hall in Dinslaken came into being through a 1913 takeover of the district court building erected in 1896–97 by the state architects Hillenkamp and Müller. The stately Gothic Revival stepped gable originally built for the district court was also suitable for the town hall. Yet, despite its distinctive character and its preservation and use after the Second World War, the town hall was demolished in 1964.

The surprisingly impressive town hall in Wattenscheid (a district of Bochum since 1975) has the air of an early Baroque palace. For the growing industrial town, the 1838 building was extended in 1884 and given its uniform façade by Peter Zindel in 1896–97. Although it is situated on a small side street and today has a small forecourt, the new rear extension by Georg Vinzelberg built in 1955–57 pays homage to the car by facing the main road with its curved façade. Although it takes the form of a modest office building with its simple grid façade, the building’s public character is stressed by its chunky corners and welcoming canopy over the central entrance.

One of the striking new buildings erected during the region’s industrialisation and metropolitan expansion was Gelsenkirchen’s town hall at Machensplatz on the edge of the city centre. Despite the award of three prizes, it was built in 1895–97 to the plans of one of the judges, the Cologne diocesan architect Heinrich Wiethase. With its pinnacle-crowned gables, it borrows elements from North German Brick Gothic, claiming a Hanseatic history, as it were, for the young industrial city. With its tower at the corner of an asymmetrically composed structure, it takes up a building type that was widespread in the Empire and had also previously been used in Essen and – as a contemporary critic put it – “in its picturesque grouping is the image of a town hall”. Although it had survived the Second World War almost unscathed and continued to be used by the local police, it was casually demolished in 1970.

The city had already had a new town hall, the Hans-Sachs-Haus, built in 1924–27. The design language of the building by the Essen architect Alfred Fischer was based on the horizontal bands of the New Objectivity of an Erich Mendelsohn, spiced with the Expressionist weightiness of brick as the material. As a modern multifunctional “urban box”, it united numerous private and municipal functions from council offices to a concert hall, while its sheer size and landmark tower provide the civic monumentality. This building, too, almost fell victim to the municipality’s demolition frenzy, but its façade has been preserved for the urban landscape with complete internal reconstruction by Gerkan Marg & Partner in 2008–13.

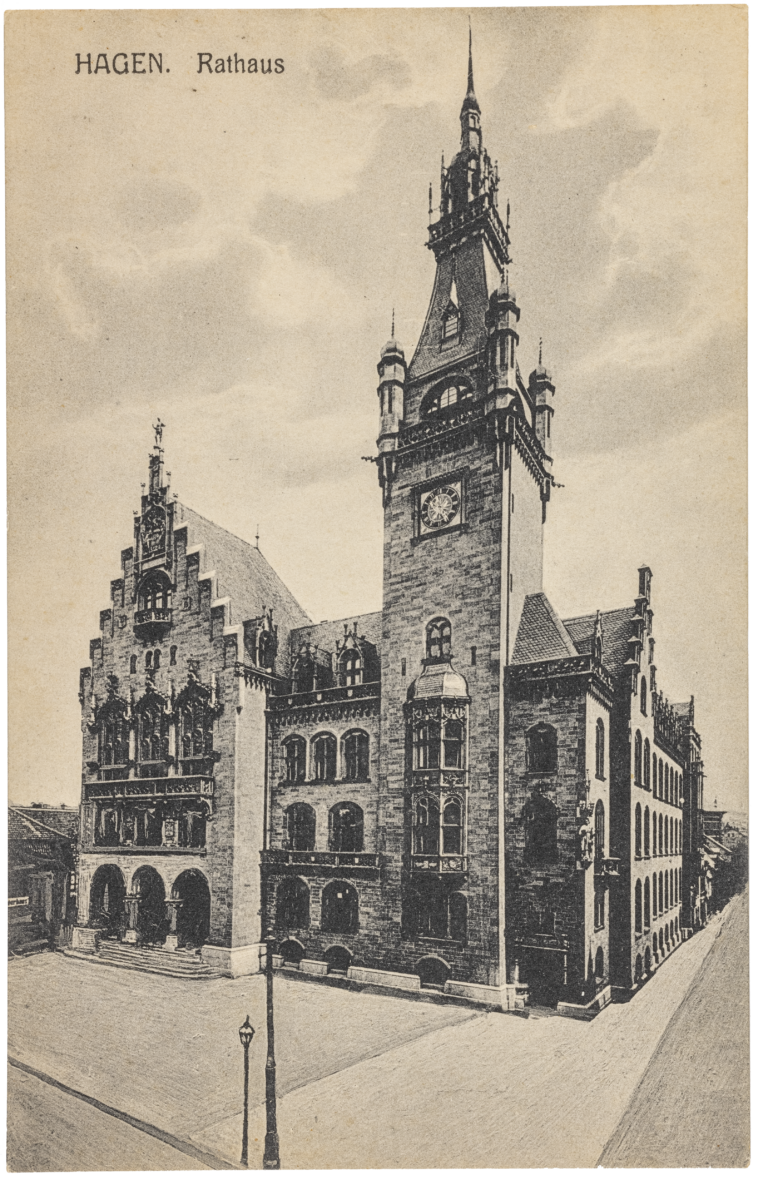

The new town hall in Hagen erected to Hieronymus Nath’s design in 1899–1904 followed the models of Essen and Gelsenkirchen in type and style: a picturesque composition at a street corner with a towering spire and dominant stepped gables takes up medieval forms and proclaims an imperial urban tradition for the flourishing industrial town. After the Second World War, the heavily damaged building was given a heterogeneous makeover in 1960–65 to the plans of Wiehl, Rosskotten and Tritthart. The council hall and offices were housed in a steel-frame-enclosed box and a high-rise block, and the tower with the adjoining parts of the façade was refurbished and fitted with a new finial, a lantern reminiscent of a lighthouse. While the 1960s buildings have already gone, cleared to make way for the construction of a new shopping centre, the tower is still easily recognisable as a symbol of the town hall and keeps alive the memory of municipal dignity.

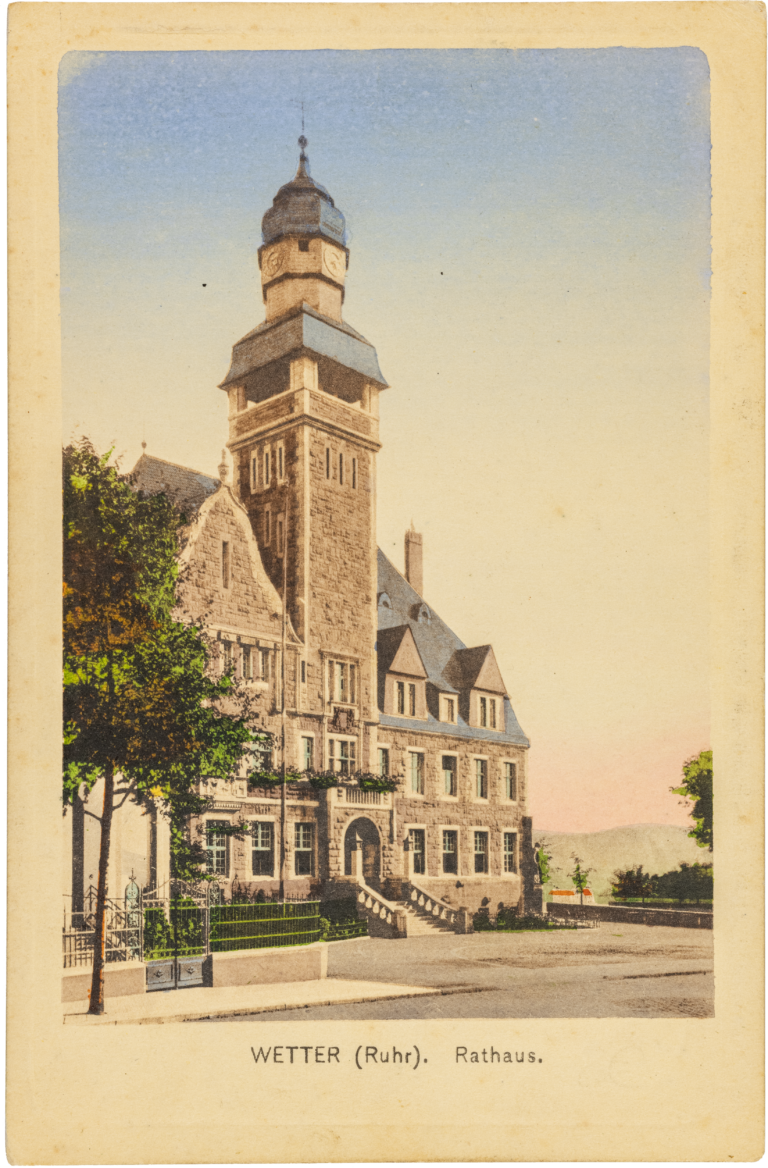

In the chronological series of the town halls of Hamborn, Gladbeck and Wetter, it is possible to trace the success of this type of town hall and its stylistic transformation. All three buildings function as structures in their own right with a tower and gable elements. On Hamborn town hall built in 1902–04 by Robert Neuhaus, medieval details have yielded to a Renaissance gable, which, however, in its ornamentally reduced and two-dimensional design, seeks an interpretation less as Historicism than as Modernism. Elaborate detailing in the novel Jugendstil (German Art Nouveau) is then evident on Gladbeck’s town hall of 1906–10 by Otto Müller-Jena. On the site of two 1960s office towers, it was supplemented in 2004–06 by an extension that not only creates a reference to the old building with its gables, but is also arranged to create a new town hall square. For its part, the town hall in Wetter by Gustav Werner dating from 1907–09 follows the reduced Neo-Renaissance style in rusticated Ruhr sandstone. The contextual adaptability of this picturesque building type is exemplified by the town hall in Herdecke, inaugurated in 1913, in which the architect Wiehl combined two existing Old Town buildings, converted them and added the tower now considered indispensable for this type of building.

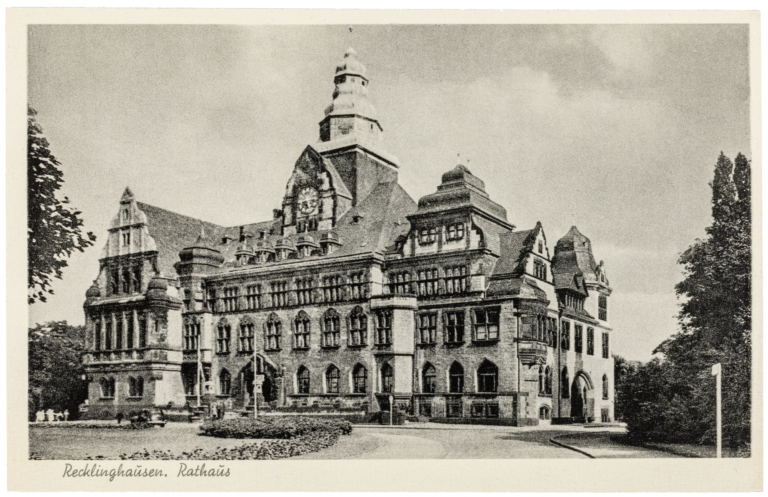

Recklinghausen’s town hall from 1904–08, also the work of Otto Müller-Jena, stands out typologically, stylistically and in its urban setting. Situated in an open space next to the medieval town in front of a park, the building has something of a palatial look. This impression is reinforced with a central section symmetrically seated in the structure, accentuated by a ridge turret perched on the central axis. At the same time, Müller-Jena counteracts this symmetry with the asymmetrical positioning and design of the gables. This complex composition thus oscillates between axial and picturesque effect. The same is true of the elaborate details, which evolve from Renaissance and Baroque forms towards a quasi-organic Jugendstil style. For all its architectural originality, the building with its tower and gable elements remains readily identifiable as a town hall building in its contemporary context. In an online competition organised by the Land government in 2020, this magnificent and well-preserved building came top as North Rhine-Westphalia’s most beautiful town hall.

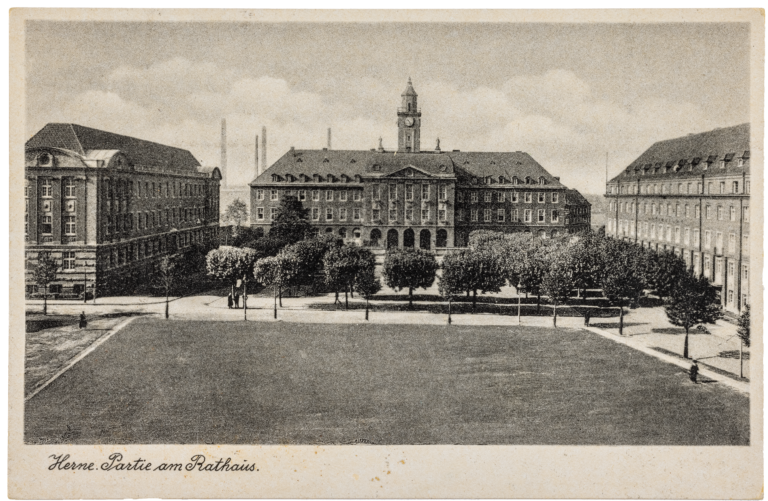

The town hall in Herne with its square is a striking example in its urban ambition. With the incorporation of new districts in 1908, the municipality of Herne needed a larger town hall building. A competition was therefore announced the same year. After a lengthy process, Wilhelm Kreis was finally commissioned in 1910 to design the building, which was completed in 1912. Kreis’s building, whose brick front and gable-crowned central avant-corps recalls palace buildings of the Münsterland, is identified as the town hall above all by its tower. Centrally in front of it, a square was conceived from the beginning as a “Marktplatz” (the original name meaning “marketplace”) and the town’s new central public space, today’s Friedrich-Ebert-Platz. The sides of the space were subsequently occupied by further public buildings: to the south by the district court from 1914–19, and to the north by the police and council office building from 1927–29. Through the stylistic shift from Neo-Baroque to monumental functionalism, however, all three buildings are linked by the use of brick to form an ensemble; the square, in turn, is lent cohesion by the high walls of the façades despite the lack of the originally planned eastern end to the square.

Comparable in its metropolitan monumentality to the town halls of Schöneberg and Spandau in Berlin is the town hall of the municipality of Buer (since 1928 a district of Gelsenkirchen), which was built in 1910–12 to the design of the government architect Josef Peter Heil. This was preceded by a competition in 1909, but the outcome was rejected. Situated on a street corner, the building cleverly makes space for a forecourt in order to enhance the building’s architectural impact. The staggering of depth and height is crowned by the town hall tower rising up in the corner behind the building. The design of a city forum, which was to be an architecturally framed square in front of the town hall, dates from 1925.

Located next to the town in a park, Datteln’s town hall built in 1912–13 by Karl Förster has all the characteristics of a stately home. The central ridge turret with its clock echoes the iconography of the town hall tower widespread at the time. With its monumental pilasters and its almost ornament-free architectural language, it lends expression to the aspirations of the Reform architecture of the Deutscher Werkbund with its leanings towards the architecture of c.1800, as expressed by the title of a book on the subject by Paul Mebes (“Um 1800”) from 1908.

Unna’s new town hall, which came into being in 1914 by converting an industrial mansion on Bahnhofstrasse, was also a palatial building in the style of Reform architecture. Nothing of it is visible today, as it was demolished in 1968 after a fire. It is part of Unna’s long history of the building, modification and demolition of town halls. The first town hall stood on the south side of the market square and is mentioned in a document in 1346. A new building was erected on its site in 1489 for the Hanseatic town, but after several alterations it was demolished at the end of the 19th century. In the meantime, the town had put up a replacement on the north side of the market square in 1829–34, which still exists today in modified form with the arcades added in 1925. In 1986–88, a large new building with a town hall square was erected to designs by Dieter and Ulrike Kälberer.

The town hall of Mülheim an der Ruhr designed by the architects Arthur Pfeifer and Hans Grossmann in 1912–15 is intimately linked with the town’s public spaces. They won third prize in the competition held in 1908. They divided the building volume into a main building overlooking the arcaded town houses flanking the triangular town hall marketplace and a side building which, with its court of honour and town hall tower, faces Friedrich-Ebert-Strasse, the road leading to the town centre. These classically conceived town hall squares were part of a spatial configuration designed by Pfeifer & Grossmann in Mülheim’s town centre that also incorporated the landscape space of the river Ruhr with the municipal hall that they also designed.

Bottrop’s town hall, built in 1914–16 to Ludwig Becker’s design, also uses the task of building the town hall to create urban spaces. The main building of the town hall with its tower rising behind it is conspicuously located on a street corner, but steps back a little to make space for the town hall square (today Ernst-Wilczok-Platz). Droste-Hülshoff-Platz is separated from it by a projecting wing. Together the two squares formed a spatial configuration, just as praised by Camillo Sitte in his urban planning book – today, however, it has been completely destroyed by the lowered car park at Droste-Hülshoff-Platz.

Town halls in the Weimar Republic (1918–1933)

Town hall design in the new republic showed great continuity with the preceding imperial period. The town hall in Witten by Franz Heinrich Jennen also creates a public space on a corner. Winning second prize in the competition held in 1912, construction only began after the war in 1921 and was completed in 1926 after several revisions of the plans. Its classicism is rooted in the architectural reform discussions of the pre-war period, while also illustrating the staying power of “c.1800” traditionalism in the ostentatious architecture of the Weimar Republic. Bochum’s town hall already mentioned earlier was also prefigured by a competition in the imperial era and was then only realised in the Weimar Republic.

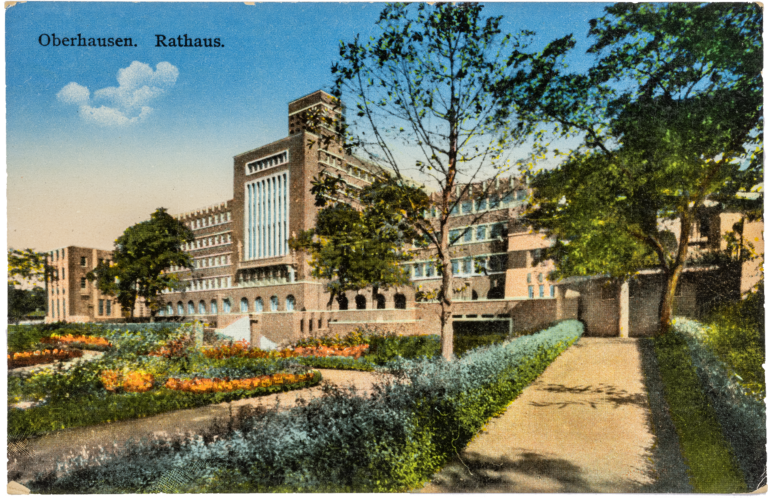

The new town hall in Oberhausen, built in 1927–30 to the design of the city architect Ludwig Freitag after a competition in 1910, stands alone in a park. The modernity of the emerging industrial city was reflected in the architecture, which combined the picturesque cubic abstraction of the De Stijl movement with the Brick Expressionism of the Amsterdam School. But Oberhausen was also keen to include an urban showpiece space, the Friedensplatz. First, in 1904–07, the district court was built as a monumental building with a dominant Neo-Renaissance gable. In 1924–27, the rectangular space was shaped by the two elongated peripheral buildings designed by the city architect Freitag, which housed the police headquarters, the Reichsbank and council offices. The formal language of Brick Expressionism harmoniously followed the Brick Renaissance of the district court. The blind arcades gave the buildings an urban element with the aim of also architecturally underscoring the buildings’ public character. In Oberhausen, the town square and the town hall are side by side.

A very special central political building of the Ruhr region is the building of the Ruhr housing association Siedlungsverbands Ruhrkohlenbezirk (SVR), today’s Regionalverband Ruhr (Ruhr Regional Association) (RVR), in Essen, built in 1928–29 by Alfred Fischer. If the cities of the Ruhr region had been merged politically into a single municipality, as happened with the creation of Greater Berlin in 1920, for example, this would have become the town hall of the Ruhr region. Instead, an association emerged in 1920 that was responsible for regional planning tasks such as integrated transport routes and continuous green corridors, but left the towns their municipal autonomy. This was emphasised by the association’s director Philipp Rappaport in the booklet published to mark the opening of the building: “The administrative building of the housing association is therefore not a town hall or a government building or an office building of a large industrial group or the like. There are building types for all these things (…).The building was not to dominate the centre of the town like a town hall, for example; it was not to express the grandeur and monumentality of a government building; it was not to have the uniform style of an office building for the employment of people in their hundreds. It was necessary to create something of its own here, something particularly appropriate to the new organisation.”

For Fischer, who shortly before had designed the Hans-Sachs-Haus in Gelsenkirchen with its tower, the task now involved finding the appropriate form for a political administrative building without competing with the municipal town halls. He achieved this above all by dispensing with a prominent tower, then an integral feature of town hall iconography. Nevertheless, he achieved a certain monumentality by staggering the rounded structures at the corner of the building, where the main entrance is also located. Contrasting with the horizontal cornices of the rows of windows, these solid vertical wall sections give the building a dignity in appearance without an iconic tower challenging the town halls of the municipalities.

Town halls in the Federal Republic of Germany (post 1945)

The continuous history of imposing town hall buildings in the Ruhr region was abruptly interrupted by the rule of National Socialism. In fact, no monumental town hall project challenged the Führer’s claim to leadership from 1933 to 1945. It was not until after the Second World War that building town halls was called for again. It was firstly a question of restoring or rebuilding destroyed or damaged buildings. Secondly, in the aftermath of the National Socialist dictatorship, there was renewed interest in lending special expression to the democratic nature of the new political institutions. While many town hall projects of the early post-war period were initially programmatically low-profile or deliberately referred back to the earlier tradition of the democratic town hall, more ambitious plans for town halls evolved in the course of the Economic Miracle that not only sought to express a new era with new forms in new dimensions, but also led, in a surge of reckless abandon, to a wave of demolition of recently restored historic town hall buildings.

On the ramparts at the edge of the Old Town marking the end of Neumarkt stands Moers town hall by Heinrich Hauschild and Rainer Runge, built in 1951–53. Its slightly convex main section with its angled wings is positioned in the landscape, detached from the line of the street. The solid rendered building with its hipped roofs and its striking entrance tower with a pyramidal roof, however, presents itself as a tradition-conscious new building that wants to be recognisable as a conventional town hall with its characteristic tower. Instead of a Modernist design in concrete, steel and glass, the community chose a traditionalist building. The council also explicitly requested a town hall tower, the roof of which citizens were able to choose from alternative models in 1952. The town hall in Waltrop, designed by Wilhelm Seidensticker in 1955–56, also stands as a modest elongated structure extending along the main road fronted with greenery instead of a classical urban space. With its row of striking pilasters, however, it also makes its claim to prominence – and the continuation of the asymmetrically positioned entrance avant-corps in a tower with a monumental clock takes up the well-established theme of the town hall tower in a readily readable manner. A very similar approach was taken with the new Wesel town hall, which was built a little earlier.

The town hall in Dorsten, built in 1954–57 to designs by Hein Stappmann and Karl-Heinz Schwirtz, takes the form of an office building in the country. It can be considered a paradigm of architectural and urban functionalism, in which distinguishing architectural features are dispensed with, as is its integration in the urban setting. The 1957 town hall in Herten designed by the architects Hinderkott and Kamperhoff also does without distinctive architectural features. Opening onto the landscape, the multi-winged brick building at best hints at a public function through its narrow, asymmetrically positioned central avant-corps above the main entrance and its clock, without any allusions to conventional town hall iconographies.

Lünen’s town hall was built programmatically as a new building after the Second World War. The young Berlin architects Werner Rausch and Siegfried Stein won the 1954 competition, the jury for which included Hans Scharoun. Their design, which was then also implemented, set the high-rise apart from the town, conceived as a stand-alone building out in the country. It was intended not as an addition to the existing urban fabric in a modern formal language, but as a deliberate contrast. In this way, their design followed the ideas of Hans Scharoun, who had asked civic leaders in the run-up to the competition not to specify a concentration of building masses in the competition brief, but to allow a “polar relationship”.

The design for the new town hall was by no means functionalist, but also included the ceremonial tasks of such a building, as Rausch himself pointed out: “A town hall is something other than and more than just an administrative building. The meaning and significance of our municipalities’ independent self-administration should explicitly take precedence over the purely functional nature of the building.” This political and aesthetic aspiration was achieved through a series of distinct architectural and urban design measures. First of all, there is the free ground plan, which can be interpreted as a formal counterpart to municipal freedom. Nevertheless, the building is not an expression of untrammelled freedom, but of a freedom that obeys rules. Thus the various service and administrative rooms are all designed with right angles, as their practical functionality requires. However, these groups of rectangular rooms are arranged in such a way that skewed and asymmetrical spaces are created between them, generating a tension that encourages movement.

The asymmetrical circulation space culminates in the central hall, which not only forms the public centre of the building in the usual sense, but also the new political marketplace. Since the building stands alone in a park landscape, the public square that is actually expected is imported into the building. With its two storeys, its mighty columns, its clerestory-like lighting and its artistic decor, the hall echoes the dignifying formulae of architectural history, while at the same time, through its free, asymmetrical arrangement, having a totally novel effect and creating an unusual monumentality. Entirely in contrast to the dictum of unassuming functionalism, this was precisely the architects’ intention, as Rausch confidently proclaimed: “Centrally located is the great hall, the grand ceremonial space of the people. Certainly, some may find the term ‘ceremonial’ grandiloquent, but there is a current tendency towards the levelling of concepts. In building a town hall, the justification was there to go for such accentuation.”

The exterior also illustrates the architects’ project-specific efforts to avoid off-the-peg solutions. The grouping of the buildings’ parts results in a “plasticity of the building volume” that distinguishes the building strikingly from any grid-based slab structure. All the same, the resulting plasticity is so distinctive and unusual that the building is not easily identifiable as a town hall. Nevertheless, the impression of something special is immediate.

The town hall’s political dimension is clearly reflected in the words on display in the building, uttered by Berlin’s Mayor Willy Brandt in his capacity as chairman of the German Association of Municipalities at the inauguration on 5 October 1960: “This building must be more than a landmark and the centre of an ascendant town. It is a concrete document, a commitment of our people and our State to development and progress. It is a monument to peace, a symbol of freedom.”

In Lünen, however, this ambitious new start also marked a break with the town’s history. Back in the 19th century, Lünen’s medieval town hall dating from the 14th century had been demolished and replaced by a new one in 1847. And the latter was finally erased from the townscape in 1968, despite having survived the war without damage.

As a town of the northern Ruhr region newly founded in the 20th century, Marl was able neither to build on its own history nor to showcase its aspirations to modernity as a contrast to the old. The Dutch architects Johannes Hendrik van den Broek and Jacob Berend Bakema triumphed in an international competition for Marl’s town hall held in 1957. Their design was executed in a reduced form in 1960–67, as the town had failed to grow on the scale predicted.

Reflecting the grouped and scattered town of Marl, van den Broek and Bakema also broke down the town hall building into several structures. A low, flat building with a forecourt appropriately accommodates the assembly rooms, while the offices are distributed in four tower blocks, which were to stand tall on the town’s skyline in an asymmetrical arrangement. However, they were unable to achieve this effect because only two of the towers were erected and, in addition, the view of them is now partially obscured by even taller residential buildings in the immediate vicinity.

The adoption of the usual town hall elements – forecourt, hall building, tower and clock – is rendered almost unrecognisable by the free composition, so Marl’s town hall catches the eye primarily through its unusual structural features. The assembly building containing the council chambers is spanned lengthwise by a pleated concrete construction in an engineering tour de force that demonstratively presents itself as a frame towards the square; in the high-rise towers, the various storeys are suspended from above from a central mushroom construction, as also outwardly visible from the vertical tensile members on the façades. Marl’s town hall is thus an expression of an optimistic age of possibility, in which even the seemingly structurally impossible could be engineered, unhampered by the past.

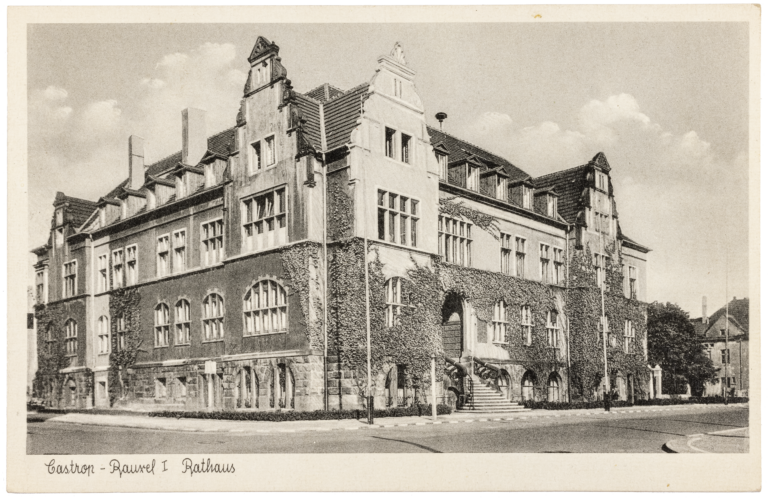

In 1966, the municipality of Castrop-Rauxel embarked on a major project with an international competition for a new town hall. As a new urbanised centre, it was to connect the various settlement complexes and replace the old Rauxel town hall. Built in 1904–05 with its Neo-Renaissance gables on a street corner, it had served as the town hall of the then newly founded town of Castrop-Rauxel since 1926. The competition was won by the Danish architects Arne Jacobsen and Otto Weitling; the complex was realised in 1970–76, with Otto Weitling being joined by Hans Dissing after Jacobsen’s death.

The concept and design were ambitious. The new centre was not to be constituted by a town hall alone, but also by a forum with other public facilities such as the municipal hall with a theatre and the Europahalle for a variety of events. The northern edge of the forum is defined by the town hall, a 250-metre-long structure with solid brick-clad pillars. The council chamber projects into the space as a free-standing structure and gives an impression of tent-like temporality with its downward-curving suspended roof design. The southern edge is also framed by an analogous, somewhat shorter wing, from which the municipal hall and the Europahalle also sweep into the space with their suspended roofs.

However, the complex was unable to achieve the goal of creating a town centre due to its urban design and architectural approach. Surrounded by expressways in the shadow of a motorway junction, it is a typical product of the car-oriented town in being primarily accessible to cars with its underground car park. Pedestrians, on the other hand, are practically denied access: in the north, the monumental block screens off the link to the existing residential neighbourhood; on the other sides, urban neighbourhoods separated by wasteland and sports facilities are far too far away to be reached on foot. In addition to its inaccessibility, the mono-functionality of this civic centre effectively stifles urban life in the open space. Architecturally, Europaplatz is also not designed as a public square. The buildings of the event venues extend into the space and thus effectively take away part of it. Their architectural design is also more reminiscent of stadium buildings and has earned them the nickname of “ski jumps”, thus conjuring up alpine rather than urban imagery.

Bergkamen town hall was built in September 1974–76 by the Bergkamen architect and chairman of the SPD council group Friedrich Karl Schulte. The office wing and the council chamber are split into two buildings resembling a swimming pool next to office blocks. The intention to create something meaningful is unmistakable; however, the specificity of a town hall remains indiscernible due to the refusal under the dictum of Modernism to use conventional symbols. It was not until the 1980s – with the new town halls in Dortmund and Unna for example – that the desire for ostentation in the city centre returned. The town halls are once again located in the city centre on a square that they also dominate, and are also conspicuous architecturally as significant public buildings – examples of municipal monumentality.

Conclusion

In overview, the Ruhr region shows itself to be a region surprisingly rich in impressive town hall buildings. This is not surprising, since it is a region with an extraordinarily high density of towns and cities. Nevertheless, we have become accustomed to seeing the infrastructural relationships rather than the individual urban cores with their urban identities as the specific feature of the Ruhr region. Here, the long history of town hall buildings shows that attempts have been made at different times with various means to express the importance of the municipality with the aid of grand town halls – not infrequently in competition with surrounding towns. Hardly any town hall building seeks solely to serve a practical purpose; almost all of them also aim to highlight the town’s value, identity and self-determination, i.e. to be a municipal monument.

The historical review also shows that at certain times certain building types and elements rose to prominence in town hall design. Characteristic of medieval town halls is the two-storey structure with a prominent gable overlooking the marketplace, arcades with a hall for commerce and jurisdiction on the ground floor, and a large hall for council meetings and other gatherings on the upper floor. Dortmund’s town hall – in fact one of the oldest in Europe and the oldest surviving town hall in Germany until its demolition in 1955 – was a fine example of this. One variant was the side-gabled arrangement, which facilitated a longer arcade on the ground floor. With the exception of Rheinberg, the medieval and post-medieval town halls in the Ruhr region did not have a tower and thus did not compete with churches.

The tower only became a widespread town hall symbol on the new town hall buildings of the large cities in the age of industrialisation. The Flemish town halls with their towers often placed centrally in the façades, as used for example on the large town hall building projects in Hamburg, Berlin, Munich and Vienna in the mid-19th century, served as models here. This type of building required a free-standing structure overlooking a correspondingly large square. In more cramped urban situations, a second type developed in which the iconic building elements – tower, gable and council chamber window – were composed together in an asymmetrical picturesque composition on a building on a street corner. Essen town hall resulting from the competition in 1874 established the model for town hall buildings in the German Empire; numerous town halls in the towns of the region also followed this example, which, taking the example of Gelsenkirchen town hall, was attested to be “the image of a genuine town hall”. While, referring back to medieval urban traditions, Gothic was initially the preferred style for these buildings, the basic design remained the same with subsequent changes in style ranging from Jugendstil to the Reform style with its reduced ornamentation.

In the early 20th century, another type of building was added, a palace-like structure, as exemplified by the town hall in Herne. When it came to the demonstration of municipal self-determination, the palace building was not initially an obvious choice as the starting point. It was only the greater historical distance coupled with the growth in municipal pride that enabled industrial towns to make use of this both functionally suitable and also stately type of building. In most cases, a tower and its combination with a town square identified its new function as a town hall.

In the Führer-led National Socialist state, municipal governments had little say and consequently no part in the construction of prestigious buildings. Monumentality was reserved for the state, the National Socialist party and the Führer himself. In this respect, the newly constituted towns of the democratic state after the Second World War were thoroughly able to take up the architectural symbols of a monumental town hall tradition. In all modesty, the town halls of Moers, Waltrop and Wesel with their deliberately erected town hall towers are examples of this. The conscious omission of all ostentation, also observed in the post-war period, such as on the town halls in Dorsten and Herten as purely administrative buildings, remains however an exception.

Conspicuous in the Ruhr area are the ambitious examples of the post-war period on which a “new monumentality” was envisaged through novel building types, themes and constructions, as Sigfried Giedion, a Swiss exponent of international Modernism, had already called for in 1944. In Lünen with the unusual asymmetrical and organic composition of a high-rise building visible from afar, in Marl with the free composition of a city crown using an unconventional construction method, and in Castrop-Rauxel with the monumental design of a self-contained forum, extraordinary ensembles have been created that loudly assert the municipality’s will to present itself. The fact that these examples have not caught on may be due to two characteristics that all three projects share. Firstly, they are not really connected to inner-city spaces, or even set themselves apart from them. And, secondly, they do not employ a familiar, i.e. conventional, architectural language that would make them easier to read as town halls – they have, as it were, become victims of their own innovative aspirations.

The overview shows that town hall buildings in the towns of today’s Ruhr region have been designed and erected time and again as expressions of urban freedom, municipal self-government and democracy, and civic pride. With this will to stand out – the will not only to provide space, but also to communicate – they have always been monuments of the urban, of urban culture and of urban democracy. In order to be able to communicate, town hall architecture needs signs that identify it as a town hall and make it recognisable as such. Such signs cannot be the invention of architects alone, for they must also be wanted by the municipality’s organisations and understood by the townspeople.

The historical overview shows that different architectural features can become symbols over time. However, it also shows that the lack of symbols or new, arbitrarily conceived features are not a solution either. The success story of the town hall tower reveals a number of characteristics for the functioning of architectural signs. First of all, as a tower it is primarily a monument, a building element with the character of a sign: it does not offer space for practical purposes, but makes great efforts to be simply visible from a distance. However, if it becomes a building element that can also be used for practical purposes, as in the case of the town hall office block, it loses its specific ability to communicate: Although Essen may have the tallest town hall in Germany and also the town hall visible from the farthest reaches of a town, it fails to fulfil its symbolic function because no one recognises it as a town hall. Another feature of the tower is that, as a gravity- and wind-defying structure, it must be solid and durable in order to exist at all. This makes it ideal for standing up for the town’s analogous values as well. Height and the associated visibility are further characteristics of its ability to communicate. But this is not least due to the familiarity of this symbol, as the town hall tower has a tradition that makes it comprehensible to many.

If the aim of our StadtBautenRuhr investigations has been to find out how the urban image and urban identity have been and still are moulded by buildings in the urban space, then town halls are certainly the central building task in the political sphere of the municipalities. No other building task encapsulates the political self-image and political aspirations of the municipality more than the seat of its political decisions, the town hall. The representational function is virtually inscribed in this building task. Accordingly, the towns and cities in the Ruhr region – despite numerous thoroughly idiotic demolitions – have also achieved a diverse and impressive municipal democratic monumentality in their town hall buildings.