Catalogues of avant-gardes

Christos StremmenosBy dismantling the medieval fortifications of their city from 1810 to 1874, the people of Dortmund opened the way to modernity. Considered progressive and practised in many fortified European cities of the time, this clearance of the city walls now deprived of their original function and deemed historical ballast, also marked an act of departure from the confines of the old city, which seemed to inhibit any development, out into fields that were to open up metropolitan vistas.

A timelessly distinctive monolith

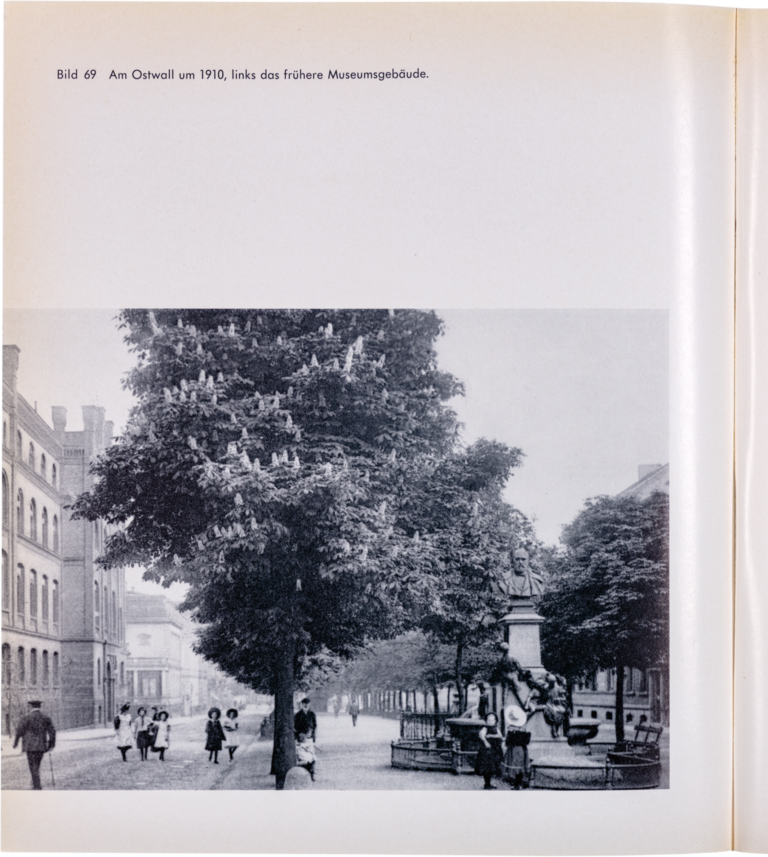

The all-pervasive industrialisation of the time brought prosperity as well as an enormous increase in population and entailed profound large-scale consequences in the physical structure of the city. In this dynamic process, a new enlightened bourgeoisie increasingly emerged that wanted to see its expectations of a modern city expressed in urban buildings. Modelled on Vienna’s Ringstrasse, it positioned many of these buildings on the new boulevard planted on both sides with rows of trees, the Wallring, which was created around the Old Town on the aprons newly reclaimed by removing the fortifications.

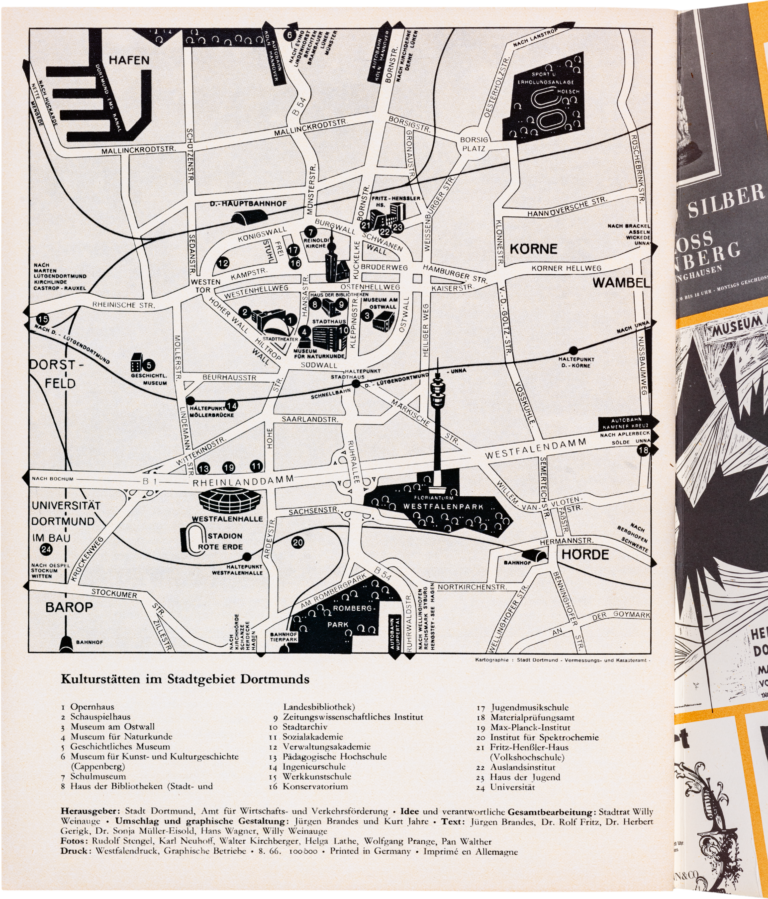

Over the years, the avant-gardes have been lining up here, in a steady succession: the city’s first railway station that opened in 1847; the synagogue built in 1900 in the historicism typical of the time, one of the largest of the German Empire; the municipal theatre (Stadttheater) of 1904, a paradigm in architectural history; the second railway station building erected in 1910 in the Reform style; the health centre (Gesundheitshaus) realised in 1961 in surging post-war modernism, the opera house completed in 1965 in a light, innovative shell construction, the municipal library built in 1999 in the spirit of Ticino modernism, the Dortmunder U converted into a centre for art and communication in 2010 – are listed here by way of example.

It is therefore hardly surprising that at this point in the city, on the Wallring, which describes Dortmund’s demarcation line into modernity, one encounters a monolith that has been ground down to the elegance of the 1950s with a rare timeless modernity, the Baukunstarchiv NRW.

Starting point of a new beginning

The timelessly distinctive monolith is the oldest surviving secular building in Dortmund’s city centre and even its surviving fabric constitutes a physical catalogue of avant-gardes. Built in 1875 by the architect Gustav Knoblauch, it originally served as the Royal State Mining Office for the administration of the expanding coal and steel industry in the Ruhr region. With obvious borrowings from Schinkel’s Bauakademie (building academy) in its internal and external structure, a building that unites organisation and abstraction with unusual perfection and which served as a model for entire generations of architects, it can be ranked among the prestigious Prussian institutional buildings of the time.

When the mining office moved out in 1910, the building at Ostwall 7 became vacant for the first time in its history. Fortunately, city building officer Kullrich had the inspiration to preserve the building and have it converted into the Museum for Art and Craft. In doing so, he anticipated a trend that would only emerge decades later in the course of industrial restructuring and become contemporary practice, i.e. the housing of art and cultural instructions in former buildings of industrial infrastructure (#Dortmunder U). The most profound and lasting structural measure he undertook in his transformative feat was the widening and glass roofing of the courtyard, the atrium originally narrowly dimensioned for purely functional purposes, which from then on formed the light-flooded heart of the building. This space became the building’s largest and at the same time the most public: an urban forum for exhibitions and events in the centre of the museum.

The principle of simultaneity

Despite the wartime damaged suffered by the building in 1944, this imposing space survived the war almost intact. In the post-war period, it was to become the starting point for a new beginning. From here, the patroness of the avant-gardes, the founder and director of the Museum am Ostwall, Leonie Reygers, organised one of the most ambitious exhibition programmes in post-war Germany from 1949 onwards, amid the ruins and with just five additionally restored rooms. Art exhibitions of the German avant-gardes of the early 20th century, denigrated as “degenerate” under Nazi rule, succeeded one another at a dizzying pace: Hermann Blumenthal (1949), August Macke (1949), Xaver Fuhr (1949), Otto Mueller (1950), Oskar Moll (1950), The Haubrich Collection (1951), Eberhard Viegener (1951), Käthe Kollwitz (1952), Franz Marc (1953), Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1953), to list just a few of the exhibitions in the early years.

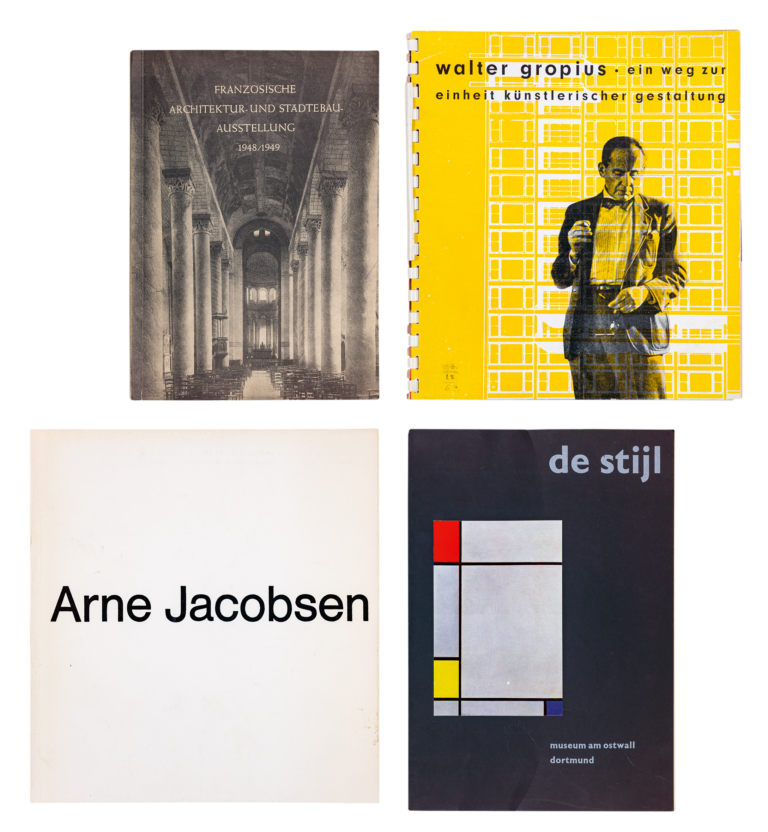

In her attempts to forge ties with the avant-gardes of the pre-Nazi era, Reygers included not only art but also architecture, arts & crafts and industrial design in various exhibitions from the museum’s opening in 1949: French Architecture and Town Planning Exhibition (1949), New Pictorial Knitting and Embroidery (1949), Arts & Crafts 1950 (1950), Old and New Domestic Appliances (1952), New Domestic Appliances in the USA (1952), New Building in Holland 1922-1952 (1952), The Architect Walter Gropius (1953), Tapestries (1953), The Werkschule Münster (1954), New Building in the Bay of San Francisco (1954), Designs for Industry (1954), “bauen + formen” in Holland (1959), The Architect Arne Jacobsen (1963), “De Stijl” (1964), to name but a few.

While this ambitious exhibition programme was attracting attention throughout Europe, Reygers was at the same time, in the spirit of the architectural avant-gardes presented in the exhibition formats from 1947 to 1956, rebuilding her ruin on the Ostwall and transforming it into a museum of modernism. As early as 1954, on viewing the first rebuilt museum rooms, designed as Reygers intended and created in the middle of the building that to a large extent still looked like a ruin, Anton Henze testified to their noble exemplarity. According to Henze, “the Muses are not only at home in these rooms, but are also active in exemplary fashion”.

Saving of a beloved House

From the very beginning, Reygers recognised the potential of the central atrium introduced by Kullrich in 1911 and the possibilities it opened up for the simultaneous staging of various event formats. She was also the one who celebrated the principle of simultaneity at the Ostwall over the years and was able to skilfully exploit it in all conceivable syntheses.

“Können und sollen Architekten erzieherisch wirken?” (Can and should architects have an educational mission?) was the title of a discussion event held on 8 May 1959 in the atrium of the museum in the midst of the exhibition “French Sculpture of the 20th Century” and organised by the magazine “baukunst und werkform”, which had excelled in its years of publication from 1948 to 1962 as the preeminent forum in the discourse on the interpretation and classification of modern architectural trends. It was from this journal that the heated controversy about the interpretative authority over modern architecture in post-war Germany, later known as the “Bauhaus debate”, came to a head in 1953 in a clash of views between Rudolf Schwarz and Walter Gropius.

The Oriental carpet temporarily laid out in the atrium for the event, marking out a space of discourse in the middle of the exhibition between Constantin Brâncuși’s sculpture “Soleil saluant le coq” and Aristide Maillol’s sculpture “L’Harmonie”, is reminiscent of appropriation strategies of a modern nomadism in the urban space. This made a more public appearance a decade later with the 1968 student protest movement and was celebrated pictorially in collages by the Superstudio architects’ collective in 1971/1972.

The showcased jarring of styles was also to be understood as a programmatic provocation. Marcel Breuer’s cantilever chair, a piece of furniture symbolising the fusion of art and craftsmanship in the spirit of the Bauhaus reform endeavours, was placed on a woven floorcovering, a field of traditional craftsmanship, and at the same time brought the conflicting views and emotions of the seated participants in the discussion into visible resonance and dissonance over the relationship between tradition and innovation in the context of a design mission shaped by times of changing industrial means of production. Another designer of such a cantilever chair took part in the discussion at the paper-strewn table: Sergius Ruegenberg, the later designer of the “Tugendhafter” chair (1986).

The conceptions and practice of “Das neue Bauen” (The New Construction) in its post-war manifestations were discussed by the editors of “baukunst und werkform” Hans Koellmann and Hartmut Rebitzki with their guests with visible differences of opinion. The role of the commissioning client and the issue of how users can be involved in the design process were taken up. In the furnishing of their own new modern homes, these users resorted strikingly often to items reminiscent of the ornamental carpet temporarily and provocatively unrolled on the historic marble paving of the Museum am Ostwall. No conclusive answer was found to whether and how architects should more forcefully pursue an educational mission in helping the general public to cultivate good taste, and the positions remained polarised. Both the achievements of New Construction, which had yielded an enormous improvement in hygienic conditions for many, were proclaimed, as well as voices testifying to the characterless of modern architecture and accusing it of promoting neglect, even the neglect of public spaces, a phenomenon particularly evident in the grounds of newly built estates of the time, for which none of the residents felt responsible.

Worthy of note was not only the carpet that defined the discussion space, but also the arrangement of the audience in a circle around the debaters. Like in an arena, the experts vying for their positions were showcased in the centre, surrounded by interested urban citizenry.

Leonie Reygers pursued this universal approach of the simultaneous presence of event formats in a well-organised venue, which she described as a “combination of art and life”, until her retirement in 1966. Reygers’ pioneering spirit still permeates the building at Ostwall 7 today, which has lost little of its contemporary aura and which represents nothing less than the material legacy of the patroness of the avant-gardes. The museum director’s successors continued this tradition and established the building as a venue for European modernism.

Saving of a beloved House

When the Museum am Ostwall moved into the newly furnished rooms in the Dortmunder U (#Dortmunder U) in time for the European Capital of Culture RUHR.2010, it looked as if the historic fabric at Ostwall 7, which by then had been dedicated to art and the avant-gardes for a century, was finally doomed. With the announcement of the city’s demolition plans, the citizens of Dortmund remembered the building dear to them on the Ostwall, one that had introduced generations of them to the world of the avant-garde, and organised pressure groups to save it. These efforts were supported by research work in historical collections, archives, libraries and by interviews with surviving witnesses, which brought to life the history of the building and the stories that loomed large in it, as if seen through a telescope. The findings of this work have been compiled, among other things, in academic articles by the chair of History and Theory of Architecture at the TU Dortmund University and in the book “Das alte Museum am Ostwall” (The former Museum at Ostwall) by Sonja Hnilica. The building at Ostwall 7 was saved thanks to the public activism supported by scholars and, following remodelling by Spital-Frenking + Schwarz Architekten, has been home to the Baukunstarchiv NRW since 2018.

Having been saved from demolition through memory tapped by research into historical plans, photos, files, written materials and publications, it is a stroke of good fortune that this house is now dedicated to the preservation and transmission of such architectural and cultural assets and documents. The story of the preservation of the building is also a story of the avant-gardes believed forgotten, now amassed here on the shelves and in the cabinets of the archives in vessels, cases, rolled-up plans, and boxes, stored side by side despite their heterogeneity, and kept safe for the future. For exhibitions and events, they are released from their catalogued containers and are presented once again as viewpoints in the centre of the discourse space, in the atrium of the avant-gardes, the heart of the Baukunstarchiv NRW.

The present text was first published in: Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, Wolfgang Sonne, Barbara Welzel (ed.): “Und so etwas steht in Gelsenkirchen…”, Kultur@Stadt_Bauten_Ruhr, Dortmund 2020, pp. 58–73.