The building’s public character

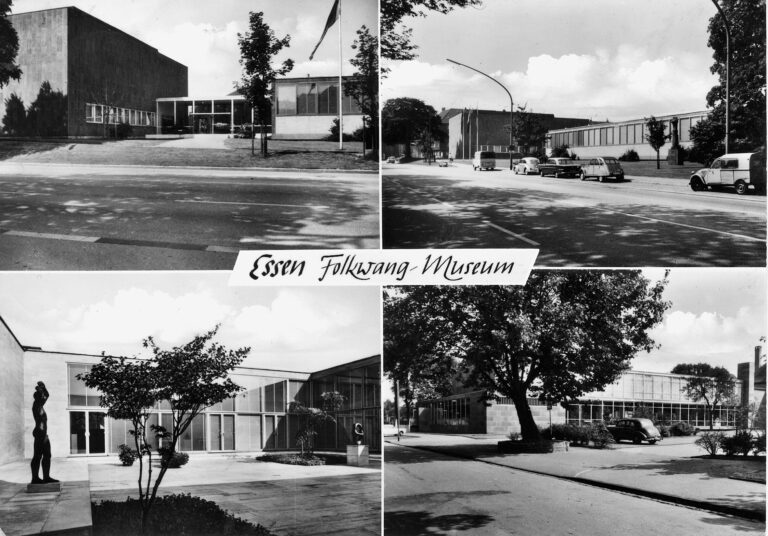

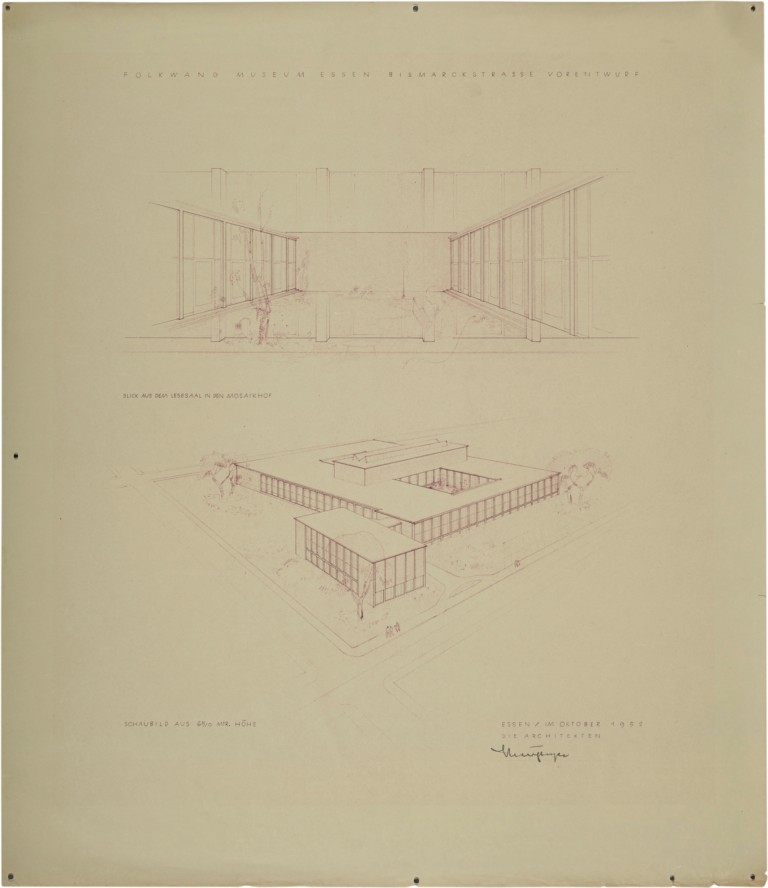

Sonja PizonkaThe Museum Folkwang opened in 1960 after four years for construction. Shortly after the war, initial measures were taken to partially repair the badly damaged museum building (two repurposed villas and an extension by Edmund Körner completed in 1929) for reduced exhibition activities. At the same time, planning for a new building got underway at the Essen building department. A draft from 1952 showed an all-round glazed building, but the idea did not come to fruition.

Strips of windows

Instead, the head of the building department Werner Kreutzberger, his colleague Erich Hösterey and the Essen architect Horst Loy developed a sophisticated system of light management for each side of the building. In the south, a glass façade that served as a kind of “shop window” next to the entrance pavilion; in the west, closed wall surfaces; in the north and east, strips of windows fitted at a height of approximately two metres. These admit daylight and provide the wall space needed for the display of framed artworks. Three images on a contemporary postcard show views of the museum, the entrance, the location on Bismarckstrasse and a courtyard. The fourth picture, however, shows not the Museum Folkwang, but the extension of the neighbouring Ruhrlandmuseum. This opened in 1963 as an extension of the exhibition rooms of the Villa Knaudt.

Noble, but in effect simple building materials

A year earlier, the following was said about the juxtaposition of the two museums: “In the harmonious grouping with each other, the autonomy of each of the two museum buildings is to be preserved, but the similarity of their purpose is to be identifiable in terms of scale and materials. With its green spaces, rest areas and arterial paths, the ‘museum island’ will connect to the green zone of the Holsterhausen development area”. Owing to the similarities between these two buildings, the south façade of the Ruhrlandmuseum was probably depicted on the postcard by accident.

In the new museum building, art was to be the focus of attention. “It was,” explained architect Horst Loy, “the overriding principle of the chosen approach that the building should selflessly subordinate itself to its service to the work of art and thus allow the architecture to play second fiddle to the works on display. The restraint in the structural design and in the choice of noble, but in effect simple building materials is in keeping with this aspiration.”

Slender columns

These exhibition rooms were typically furnished with carpets, chairs and a flexible partition system as can be seen in a photograph from c. 1965. A group of young women can be seen studying a booklet while a man looks at a painting. Visible in the background are the slender columns in front of the windows overlooking Kahrstrasse to the south. The blinds are pulled down to reduce direct sunlight, a measure necessary from the outset for conservation reasons. The daylight brought out the colours and surfaces of the artworks individually at different times of the day, but since there was no air conditioning, these rooms heated up excessively on sunny days. To this day, the blinds with their slats control the admitted light, but the temperature in the exhibition halls is now regulated by air conditioning.

Exterior and interior

Light and transparency were important features of museum architecture at this time. Kunsthaus Glarus in Switzerland (opened in 1952, architect: Hans Leuzinger) with its partially glazed entrance pavilion and halls with side lighting and rooflights precedes the Museum Folkwang. Also familiar to the Essen architects will have been the exhibition pavilion with its side glazing of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam directed by Willem Sandberg, which opened in 1954. About this extension, the contemporary press wrote: “[…] so passers-by outside see practically everything that is on display inside – and they should, says Sandberg. A museum, like large department stores, must invite them in by showing its contents. When the sun shines, the exterior and interior, the surrounding grounds and exhibition halls, are a light-flooded unity.”

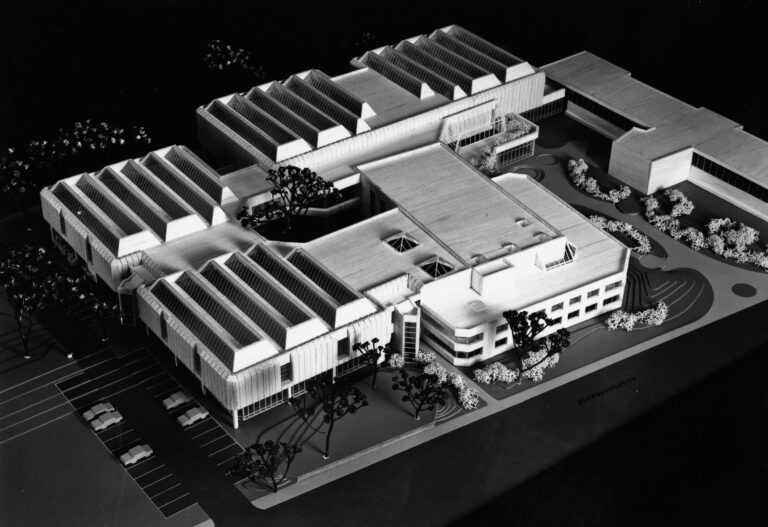

Competition 1977

After only a few years, the building of the Museum Folkwang was already too small for the constantly growing collection and its continuous exhibition activities. However, it was to take 23 years before an extension was undertaken. The competition announced in 1977 did not result in a first prize; instead, those offices that had received the two second prizes, Kiemle, Kreidt & Partner and Allerkamp, Niehaus & Skornia, were invited to combine their designs as an architectural consortium. Then, in 1983, the newly founded museum centre opened, consisting of the Museum Folkwang and the Ruhrland Museum with its collection on the history of Essen and the region.

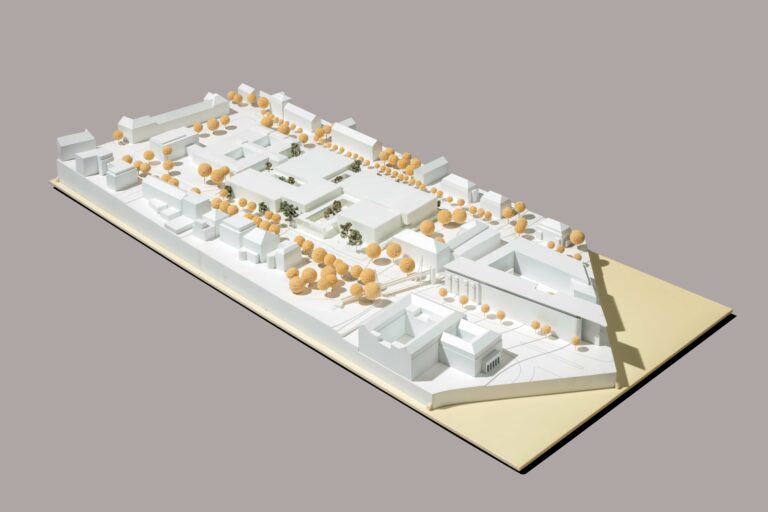

Second entrance Bismarckstrasse

The model shows the view from the west. The courtyard situation leading from Goethestrasse to the new entrance is clearly visible. Museum director Paul Vogt noted: “The new main entrance will be relocated to the quiet traffic zone of Goethestrasse. Access is via a green space with seating where contemporary sculptures and objects can be placed. A second entrance opens onto Bismarckstrasse.” This sought to optimise the urban design situation, as the location on the busy Bismarckstrasse was already deemed to be disadvantageous in 1960, the year of the museum’s opening. The museum centre building was pulled down in 2007. The Ruhrlandmuseum was given a new location as the “Ruhr Museum” in the coal washing plant of the Zollverein colliery in the north of Essen.

Enjoyment of Art

An extension solely for the Museum Folkwang was built on the site, which had been slightly enlarged through the purchase of a neighbouring property. The international competition was won by David Chipperfield Architects; the building was financed by the Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach Foundation. To illustrate his ideas, David Chipperfield had a cloth-bound book in folio format made. To supplement the in most cases digitally generated visualisations, he created a narrative in book form, with historical black-and-white photos of the old building from 1960 and modern renderings of the planned new building to illustrate the idea of connecting the two buildings. A quote by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe sets the tone: “The first problem is to establish the museum as a centre for the enjoyment of and not the internment of art. Thus the barrier between the work of art and the community is erased.”

More clarity

The design shows the new entrance situation, depicted as a partially covered courtyard. In the building’s finished state, visitors access this transitional zone between the museum and the city by stairs, lift or ramp. Visitors use it as a meeting point before entering the museum, and the café’s outdoor catering is also located here. After entering the museum building, there are no more differences in levels to overcome in the new building, with visitors moving barrier-free from the foyer to the shop, reading room and the large exhibition areas in this part of the building, and this has actually made it architecturally easier to overcome the boundary between art and the (urban) community mentioned by Mies van der Rohe. Chipperfield explains his thinking as follows: “We have stressed the building’s public character. With its courtyard, it now opens onto the street, to the city, and is highly permeable due to the many large windows. We also wanted to create more clarity. To achieve this, we located all the rooms intended for the public on a single, ground-floor level.”

The present text was first published in: Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, Wolfgang Sonne, Barbara Welzel (ed.): “Und so etwas steht in Gelsenkirchen…”, Kultur@Stadt_Bauten_Ruhr, Dortmund 2020, pp. 104–117.