Openness as a principle

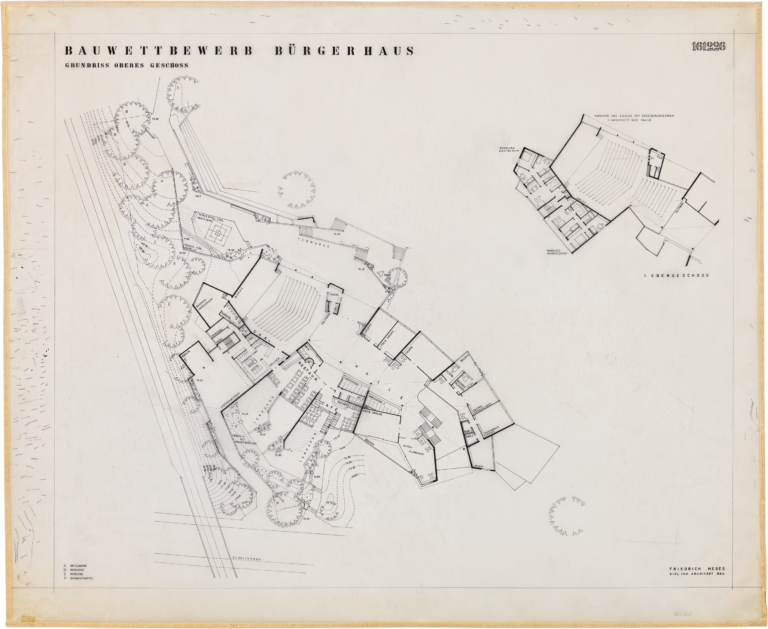

Anna KlokeThe plan illustration entitled “Bauwettbewerb Bürgerhaus” (architectural design competition for a community centre) not only shows the ground plan of an architecture set in green surroundings, but also already reveals something of the idea of the planned building and the client’s brief. Visible is a room arrangement that, rather than following an orthogonal grid, unfolds from the inside like proliferating cells around a central hall. Open staircases, a folded wall and spacious glazing with adjoining terraces creating long sight lines open up the building – both outwardly and inwardly. Room signage suggests an intergenerational, diverse and multifunctional use – from a music studio to an old people’s clubroom, and from a district clerk’s office to an open-air dance floor in the playground. All in all, one can discern a rather distinctive architecture with a diverse room layout, which was conceived with the user in mind and sensitively takes up the existing topography. The large-format numbering of the plan and the lack of a plan stamp identify the document as an anonymous entry in an architecture competition.

This is the winning design for the construction of Oststadt community centre in Essen, which, after some adjustments to the plan, was built in 1973–1976 using a combination of concrete and brickwork. As a photograph from the time of construction shows, the two-storey building is located amid greenery and at the same time in the immediate vicinity of several high-rise buildings.

The Oststadt community centre in Essen

The Bergmannsfeld or “miner’s field” is part of the Oststadt development project, a large housing scheme for 15,000 people as the city of Essen’s reaction to rising population figures. Awarded the 1966 Deubau Prize, the Bergmannsfeld was at the time still hopefully described as a “showpiece still only in its infancy”. The high-rise buildings and up to eight-storey blocks of flats were built in 1966–1973 by the “Neue Heimat“ housing association using prefabricated construction methods. The organic architecture of the community centre that blends horizontally into the landscape forms a deliberate contrast to this.

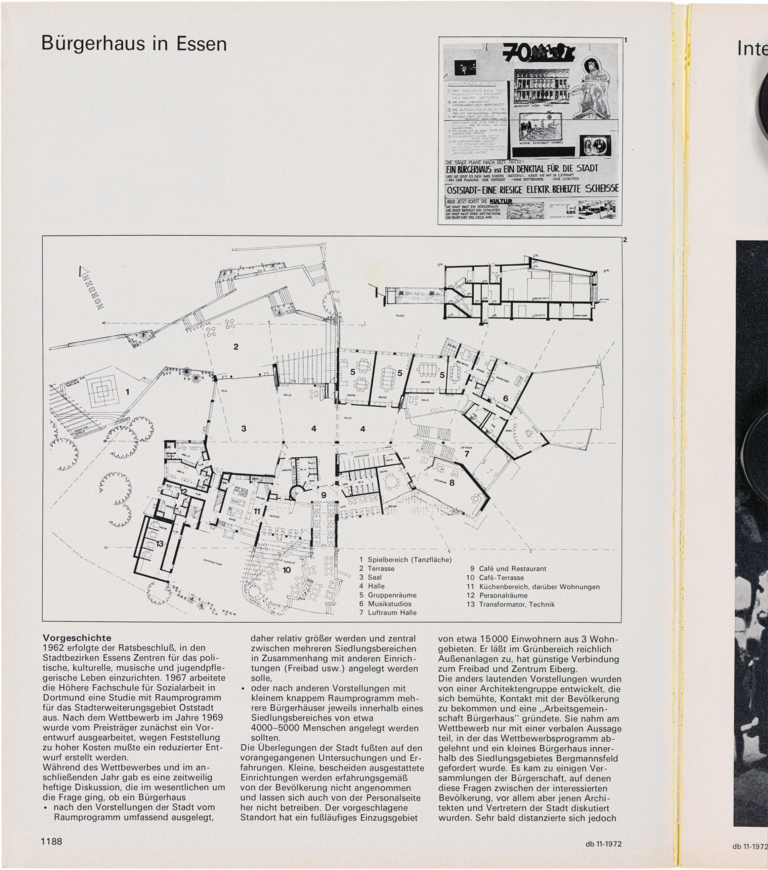

This was also demanded by residents who formed a citizens’ pressure group and insulted the Oststadt, once a model for the future of social urban development, with faecal language on posters. With the slogan “But now comes culture”, they expressed their hope that the proposed community centre could serve as a tool for urban repair. The activists praised the fact that, in contrast to the building of the Oststadt estate, an expert opinion was being commissioned, a competition held and a lot of money spent. The significance of this protest by residents for the development of the community centre is reflected in the fact that the poster was printed as part of a portrait of the centre in the Deutsche Bauzeitung magazine in November 1972.

The study on community centres in Essen

In fact, even before construction began, the city of Essen itself identified in its special committee for the Oststadt urban expansion area the “need to create suitable facilities as meeting places in the new neighbourhoods”, and thus to compensate for the lack of evolved social infrastructure. Breaking new ground, the city commissioned the social pedagogical seminar in Dortmund with a study on community centres in Essen. In the very preface, the authors paid tribute to this courage of the city of Essen with the assessment chosen above as the motto of this miniature.

The “principle of openness”

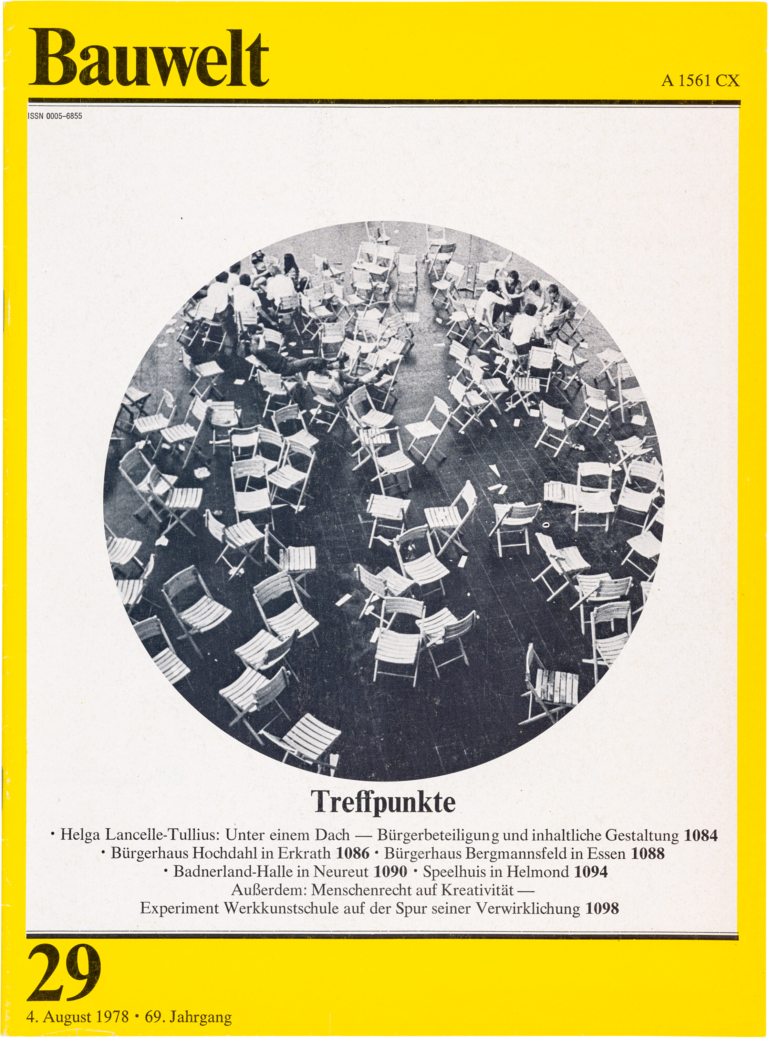

The centre was to be designed on the “principle of openness”: open to different uses, open to participatory design and open to different social groups as well as individual interests. On the basis of the Dortmund study, the city of Essen launched a competition in 1969, which was won by Scharoun’s student Friedrich Mebes (1927–2017). While still alive, he bequeathed his professional estate to the NRW Architecture Archives. It includes the above-mentioned Deutsche Bauzeitung, as well as an issue of the magazine Bauwelt from 1978 archived by Mebes on the subject of meeting places, in which the Essen community centre is also presented. The title page bears witness to the spirit of the time of the building project and illustrates its specific nature: it shows folding chairs set up seemingly at random, on which younger people can be seen sitting and chatting in casual groups. People with their feet up on chairs and screwed-up paper strewn on the floor convey an impression of informality. In fact, according to the credo of the study, the community centre was to address different age and social groups with a functional interweaving of the areas of leisure, culture and education and establish low thresholds for informal encounters by means of communal areas.

The building description

The hall of Oststadt community centre functions as such a forum, which, as can be seen in the archive photo, follows this “principle of openness”. With its open staircase, it connects the floors and, as a central distribution point, allows encounters between members of hugely differing social groups owing to the centre’s wide range of uses. By broadening the circulation areas, Mebes created a public space indoors. He reinforced this impression by continuing the slate and brick façade in the building’s interior. In addition, the outdoor clinker paving was visually continued by clinker tiles indoors and contributes to a kind of “marketplace atmosphere”. The red paintwork of the gratings and railings can also be found inside and out, guiding the visitor into the building. Structural elements such as columns and beams show formwork textures and, with their white paint, stand out against the red-brown brick walls. In addition to slate and brick, wood as a natural material also contributes to the impression of the interior, as is typical for buildings of so-called “organic architecture”. An expert opinion from 2019 also rates the centre as an “outstanding example of the ‘organic expressionism’ decisively influenced by the architecture of Hans Scharoun”. This can be seen in the typical avoidance of the right angle, the interplay of forms with bricks and in the dynamic impression of the ceiling design. The partly inclined or vaulted ceilings of different heights are clad with wooden battens in invigorating changes of alignment. At irregular intervals, long ceiling lights specially designed for the house were integrated into the pattern, but in the course of time they have been replaced by round recessed lights.

Through the warmth of the wood and the creation of various alcoves in the entrance area, the building was intended to convey homeliness and have a welcoming effect in order to reduce any inhibitions about entering. The walking paths of the valley were also incorporated into the building’s open space and routing system and contribute to its “openness”. Landscaped mounds by the reading garden and playgrounds, on the other hand, were intended to create a “gesture of screening, of seclusion for users”, according to Mebes in an explanatory report from 1971. The partial insertion into the topography and the offset of the building volumes, like the open staircases to the main entrance that creep along the side of the house deliberately seek to prevent any kind of imposition.

A non-monumental monument

Mebes himself described his work as “non-monumental architecture […] consciously different from the block-like buildings of the neighbouring residential neighbourhoods”. In fact, the community centre has been listed since 2019 – for artistic, architectural and urban design reasons. The building with its specially designated pram parking spaces has not only been designed with social practicality in mind, but also features thoughtfully designed details and an overall architecture that is rich in tension – distinct from, but at the same time in dialogue with, the location.

The present text was first published in: Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, Wolfgang Sonne, Barbara Welzel (ed.): “Und so etwas steht in Gelsenkirchen…”, Kultur@Stadt_Bauten_Ruhr, Dortmund 2020, pp. 266–279.